Ahead of the Curve featuring Dr. Larry Brilliant

January 12, 2023

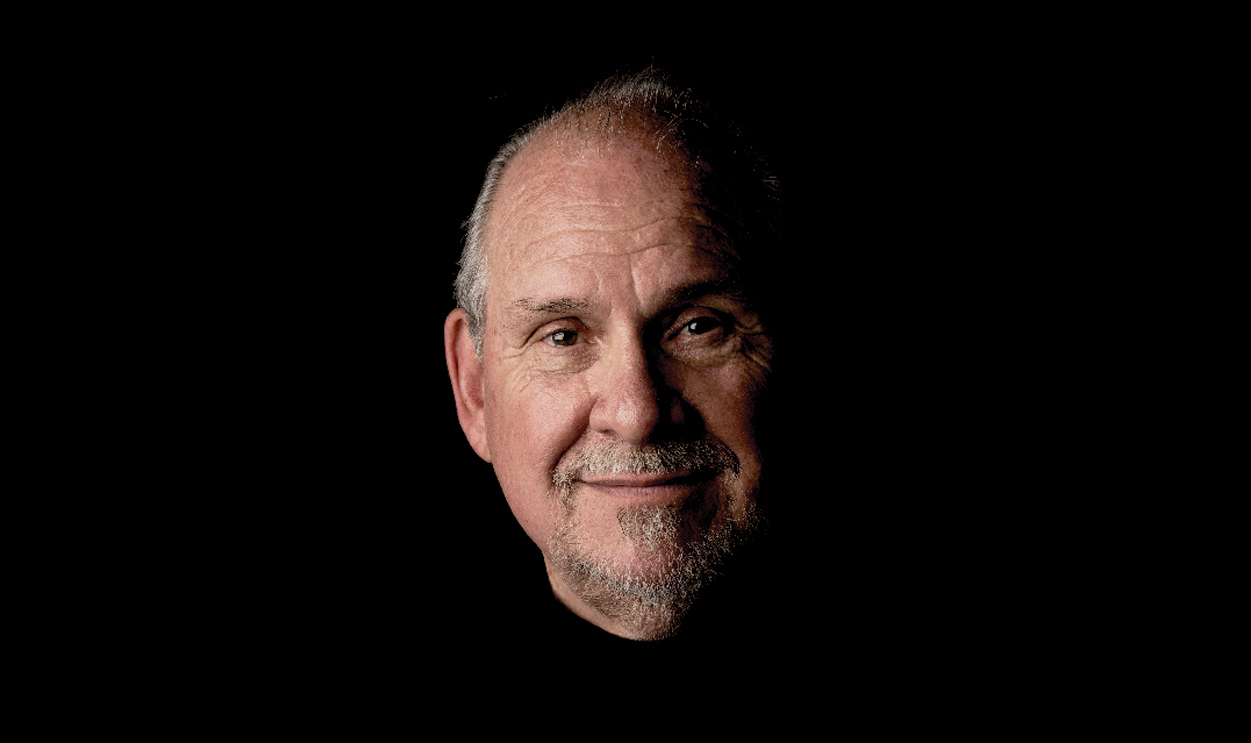

Dr. Larry Brilliant, CEO of Pandefense Advisory, Epidemiologist, Philanthropist.

Watch

Listen

Listen to "Ahead of the Curve featuring Dr. Larry Brilliant" on Spreaker.

[music]

0:00:12.1 DuBois Bowman: Thank you for joining us for Ahead of the Curve, a speaker series from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. My name is DuBois Bowman, I have the privilege of serving as Dean of the School of Public Health. Ahead of the Curve speaker series focuses on conversations about leadership and throughout this series we have discussions with contemporary public health leaders that span many sectors and we probe them to hear about their insights, their vision and their stories of perseverance. Leadership is a critical component of navigating complex public health challenges in building a better future through improved health and equity, and so we wanna hear about those important factors that shape great leaders, and we wanna hear and learn how they continue to grow and evolve so that we can think about and be intentional about training the next generation of leaders. We have a fantastic guest with us today to explore these issues. I'm delighted to welcome Dr. Larry Brilliant, who's a physician and epidemiologist with a tremendous career in public health. He currently serves as CEO of Pandefense Advisory, Senior Counsellor at the Skoll Foundation and a CNN Medical Analyst. Previously he was Chair of the Advisory Board of the NGO, Ending Pandemics, and the founding Executive Director of Google.org.

0:01:36.6 DB: Proudly for us here at the University of Michigan, earlier in his career, Dr. Brilliant was an Associate Professor of Epidemiology and International Health Planning at the University of Michigan. Dr. Brilliant lived in India for nearly a decade where he was a key member of the successful World Health Organization Smallpox Eradication Program for Southeast Asia as well as the World Health Organization Polio Eradication Program. In terms of his education, he had of course medical training, but then he also received his Master of Public Health right here at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. And all of this is just really a small snapshot of his really impressive, tremendous career. And so I'm really excited about our conversation and I wanna thank those of you who submitted questions in advance during the registration, and we've used those questions to help guide many aspects of our conversation today. So Larry, if you're ready, I'm ready to dive in.

0:02:36.7 Larry Brilliant: I'm ready. I'm very happy to be with you DuBois. It's a pleasure.

0:02:40.3 DB: Terrific. So given your remarkable career, one that to me, one of the remarkable things is that the many different facets of your career, the many different ways that you've had a positive impact on public health and equity, can you start just by telling us about your medical training? And then eventually what sparked your interest in public health?

0:03:01.8 LB: I was in Ann Arbor. I was pursuing my undergraduate degree in Philosophy. Valentine's Day my father died and I was very disheartened and I think I locked myself up in my room at South Quad and didn't go out for a long time. And I didn't get my applications in for medical school or law school until it was very late. And finally when I did get them in I was disqualified because of that. But one day I went and I was just driving a motorcycle in Detroit, and I passed by this building and it said Wayne Medical School. And I just pulled up, took my helmet off, walked in and asked to see the Dean of Admissions, and I did, and of course he laughed at me, I said, "Can I still get in?" By then it was August I think. And he said, "Well, did you take the MCAT?" And I said, "No, I didn't." And he walked out and he went to talk to somebody, came back and said, "Would you take them now?" I said, "Sure." I didn't tell him I'd just come from the dentist and they'd pulled four wisdom teeth, and I took them and then he said, "Look, I've never done this before, but we have had a dropout. If you promise to graduate and you promise to work and not ask me for student assistance, we'll let you in." So I was let in without a bachelor's degree, and I still don't have my bachelor's degree and I love that in Ann Arbor we changed their minds.

[laughter]

0:04:32.3 DB: Terrific, terrific. And then what drove you then later in the 1970s to pursue your Master of Public Health, and how do you feel that the public health training, perhaps the combined training in medicine and public health have really served you throughout your career?

0:04:50.4 LB: So my wife and I came back from India after we had eradicated smallpox, and all the people who worked on the smallpox program went back to their universities or to their government affiliations, and so we came back, we were gonna come to Ann Arbor and we thought we'd stop at Columbia, and got the idea of taking both the MBA and an MPH at Columbia. Then they told me how much it would cost.

[chuckle]

0:05:14.1 LB: I've been living in India for 10 years, I couldn't afford that. So I wrote Myron Wegman, who had been the head of the WHO regional office, and called PAHO and I said I was gonna come visit Ann Arbor. And he said, "Well, we can make you a Michigan resident 'cause you were away on good things," and then ultimately he gave me a full scholarship so I could come to Ann Arbor. It was really wonderful, and I had a great time, and Ken Warner would teach me economics and I would try to teach him epidemiology, and Bob Gross would try to teach us all population planning and of course Arnold Monto was my mentor, I love that guy.

0:05:57.1 DB: It's always interesting as I hear stories just some of the serendipity involved, and we're certainly fortunate and grateful that some of that serendipity in your pathway brought you to the University of Michigan, into the School of Public Health. I wanna ask another question. So next week here in the University of Michigan campus, we'll be celebrating the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, who continues to serve as an inspiration to all of us for his life's work to advance equity. Little known to some, much of his work specifically drew attention to health and you're aware of his quote that exemplifies this that he made in 1966, it says, "Of all forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhumane." And Larry, you published a book a few years ago called Sometimes Brilliant, where you talk about many different experiences that you've had throughout your life, and some of those we'll touch on today, but I wanna ask you about one in particular, you wrote about meeting Dr. King right here on the University of Michigan campus when he visited, and so I wanted to just ask you to tell us about that experience, what it was like, and then ultimately how that experience impacted you in your journey.

0:07:15.8 LB: Well, I think it was all about a winter storm in Ann Arbor, there was a little note in the Michigan Daily that Dr. King was gonna be on campus and speak at either Rackham, I think it was Hill, and the weather was just God awful. In Ann Arbor as the poet said, sometimes the rain can flow horizontally not just vertically.

[chuckle]

0:07:36.7 LB: And kids were not going in. And we wound up going in to see Dr. King in a cavernous hall that would hold 3000, and there weren't more than 50 people there.

0:07:46.9 DB: Wow.

0:07:47.4 LB: And Harlan Hatcher who was the president was really embarrassed when he introduced Dr. King to an empty room. Dr. King got up, started laughing and laughing and laughing, and he said, "Look, there'll be more of me to go around. Y'all come on up here on stage with me."

[laughter]

0:08:03.9 LB: And we all went on that parquet floor and we sat around, and I'd never heard anybody speak like he did. He spoke about a conviction and a commitment to a better world. And it wasn't just that there might be a better world, it might be that it would be done by much struggle, but that there was room in that struggle for everybody, everybody who was sitting around him, everybody in Ann Arbor. And then he famously said that the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice. You've all heard that, but what he said in Ann Arbor was a little bit different, he said, "The arc of the moral universe bends towards justice, but it ain't gonna bend towards justice on its own, you gotta get off your ass and jump out of your chair and leap up and grab that arc and bend it and twist it towards justice."

0:08:58.1 LB: And he had me, and he had all of us, every single person who was on that stage went down to Birmingham that summer or marched with him. I'm proud to say that the only time I've ever been arrested was with Dr. King in a march in Chicago where he was marching in support of I think the cleaning union, and we in medical school were wearing our white coats and ostensibly dangling our stethoscope to protect him in some crazy way, but we were all arrested. What they didn't realise that they'd also arrested Peter, Paul and Mary, and they sang for us, and then they didn't realise that they had Joan Baez who sang Amazing Grace. And Dr. King sang Amazing Grace, and that was it, my brain was cooked and I was all in, what an amazing man.

0:09:44.2 DB: Absolutely. Absolutely remarkable story, and even as you reflect on his words and thinking how relevant those words are for today, so very, very inspiring. Let's now shift to your career-long work in public health. And so I wanna first start by talking about your work in smallpox. For members of the audience today who were not yet alive during this time to directly witness the impact of smallpox, I thought I'd ask you to just first start by describing and painting a picture of the devastation and the daunting outlook for the world regarding smallpox, and then talk about what made you decide to dedicate yourself to eradicating the disease.

0:10:29.3 LB: It's hard to tell what virus in history is the worst in history, but certainly smallpox is a contender for that terrible title. In the 20th century alone, which actually was from 1900 to 1980, because we eradicated it in... WHO declared it eradicated in 1980. During those 80 years, 0.5 billion people died of smallpox, 500 million people died of smallpox, and they were mostly little kids. And all over the world, people didn't name their children until the 40th or 50th day because they didn't know if they would survive smallpox. In much of the world, smallpox wasn't even thought of as a regular disease because it was always there, ubiquitous and in India particularly. It's so devastating that I can only describe it by two vignettes, once when I would go to this town called Tatanagar, which was the worst exporter of smallpox in history in India. And I drove up and I had a WHO Jeep, so I had the UN seal on it, and I walked out of the Jeep, and a woman came running up to me and said, "You're a United Nations doctor, please heal my child."

0:11:41.1 LB: And she handed me her child, he was filled with smallpox lesions all over his face, his eyes were closed, and it was just involuntarily you have to hold your hands out and hold that baby, and that child had already died, and there was nothing I could do. You understand what it was like for parents to lose their kids to this horrible disease. And when I made my way into the railway station, which was where the exportations of smallpox had occurred from, I saw bodies of babies wrapped in cloth, piled high like cords of wood, it was devastating, and we don't see anything comparable, the R-naught or the index of spread of smallpox is between three and five, which is a lot compared to most viral diseases, but it's not as infectious as Omicron is today or XBB.1.5, but it killed one out of three, not one out of 1000, and there was no cure for it, there was no palliative for it, it's a horrible disease and I'm so happy that most of the people here were not born when it's still was in existence and never had to experience it. I will tell you one interesting knock-down effect, which is because it was so bad, the world came together and agreed that there'd be universal vaccination of every child born in the world, and all countries subscribed to that, there was hardly any exception to that.

0:13:07.3 LB: So we had a huge number of people in the world that were immune to smallpox, but in 1980 when we declared it eradicated naturally, country after country dropped the mandate to vaccinate kids, and what that did for monkeypox was that during the smallpox program, there were only a couple of dozen cases a year, thereafter, gradually more and more people got monkeypox, but about 3000 a year until only last year. Now, why was that? Because the smallpox vaccine protects against monkeypox as well. And so, it wasn't the eradication of smallpox that caused the surge of monkeypox, but it was the elimination of the vaccine mandate that did.

0:13:49.8 DB: In terms of a public health framework or approach or strategy, can you briefly describe what your approach was to eliminating smallpox at that time?

0:14:00.3 LB: So forever, going all the way back to Middle Ages, even before we had a vaccine, we had variolation, a process of taking this scabs of a child with smallpox and pulverising them, and then taking that powder and blowing it sometimes with an ostrich leg's bone, blowing it into somebody's nose.

0:14:18.7 DB: Wow.

0:14:19.2 LB: And that process, which occurred in Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, China, and probably in some parts of Latin America, was called variolation, variola is the name for smallpox. It provided immunity but it killed one out of 10, so you're trading the risk for a high death rate, and it was unacceptable until Jenner discovered that cowpox would give life-long protection against smallpox, and he discovered that because he had been told that the reason that we say that a milkmaid, we used to say in the ancient days a milkmaid had a beautiful complexion wasn't because of drinking milk as people thought, because milkmaids were the only people in British society who never had smallpox. Why did this one group of women, this one profession alone uniquely not get smallpox? And it was because in milking a cow, sometimes a lesion would pass from the udder of a cow to the milkmaid's fingers, and that was enough to protect them for life against smallpox.

0:15:24.3 LB: Jenner observed that, and he concluded that if he could take that pus either from the udder of the cow or the finger of a milkmaid, and he chose a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes and a cow named Blossom, and this is all part of the history that I'm sure you teach in public health, that he could transfer that to a young boy named Daniel Phipps, and he did, and that boy was the first boy who was protected against smallpox by cowpox. And the Latin name for cow is vacca, and so that process became known as vaccination. So when you encounter the anti-vax community, you might just tell them that vaccination means cow, so they're just against cows, that's all that means.

[chuckle]

0:16:11.0 DB: Terrific, terrific. So you worked with Dr. William Foege, Bill Foege on a project called Becoming Better Ancestors, and this is a series of videos featuring public health leaders discussing nine lessons learned from your work to eradicate smallpox, some of those lessons you're articulating now thus far in our conversation. You were featured in less than seven of the nine, which is seek strong leadership in management. Can you tell us more just about the leaders who you worked with to eradicate smallpox and what you feel you learned from them?

0:16:50.1 LB: Well, let's start with Bill. So Bill Foege, for those who don't know him, Bill was the head of CDC, he was the head of the Carter Center, and he's the guy who whispered in Bill Gates' ear I think he ought to start a foundation that deals with global health. He was and is the most charismatic person I have met in the field of public health, and it was Bill who found the strategy that worked to eradicate smallpox. Earlier I said that country after country vaccinated everybody through a mandate, yet that didn't work to eradicate smallpox. In India, even if they had followed that completely and mandated everybody to be vaccinated, every year there were 25 million babies born, and of course they didn't really vaccinate everybody, and that number of susceptibles was sufficient to keep smallpox propagating. Instead of vaccinate everybody or trying to, or lying about it, pretending that we did, Bill had an experience, Bill was working as a medical director of a church, a hospital in Nigeria during the Igbo Civil War, and Bill was allotted a small amount of smallpox vaccine, and there was a terrific outbreak, and he knew that he didn't have enough vaccine to vaccinate everybody.

0:18:12.2 LB: Now, in the real world, a small amount of vaccine in the face of a deadly disease would go either to the person who came and clamoured for it, or the brother or sister of the prime minister, but Bill said, "What is my moral duty?" And he said his moral duty was to allocate the vaccine first and foremost to those most vulnerable of contracting the disease. And who were they? They were the people who lived in the same household or were neighbors of a case of smallpox.

0:18:44.0 LB: So he did that, and smallpox disappeared and only in his hospital area, and he came to believe that selective epidemiological control, which this was, later named ring vaccination, was the key to eradicating smallpox, and he published a seminal article in the Journal of Epidemiology in 1969, 1970, which allowed WHO and DA Henderson, the wonderful leader of the smallpox program in Geneva to change course, and instead of vaccinating everyone to first find every single case of smallpox in India, in Bangladesh, in the four countries that remained with smallpox, Pakistan and Nepal. Of course, to do that, we had to go house-to-house, we had to have reward posters, we had to go to marketplaces, and all throughout India our team of 150,000 people made 2 billion house calls, and we found every case of smallpox, and vaccinated a ring of immunity around it and that was the strategy that led to the eradication of smallpox. By the way, that's the same strategy that has been successful... Yesterday, the Ebola outbreak in Uganda has just been declared over, same strategy. Also in Congo, same strategy. We've tried using that search and containment, surveillance and containment, ring vaccination approach. We tried using it during COVID, but as you know we really couldn't get many people to cooperate with contact tracing in the United States.

0:20:21.3 DB: Yeah.

0:20:22.0 LB: But it's the same principle. Find every case, find the most vulnerable. Allocate your resources in an equitable fashion and equity turns out to be the best epidemiology.

0:20:33.4 DB: Absolutely. Do you remember a particular moment when you felt like there was a moment of a victory if you will, when the last case of smallpox was eliminated and you knew that the disease was actually eradicated or did it actually unfold more so in phases? What was your recollection?

0:20:51.6 LB: Well, it wouldn't have been any fun if you hadn't had three or four moments that you thought you had victory and you had to start over again which is of course what happened to us. What I remember the most dramatically was on August 15th, 1975, when we thought we'd had the last case of smallpox in India and Bangladesh thought that they had had the last case, which would mean no more Variola major, that's the deadly variant that killed one out of three, Variola minor, also known as Alastrim, that was a less dangerous disease but it was still in Somalia and it still would have to be eradicated, but we were sure that we had eradicated smallpox. We'd gone six weeks without a case, we had a great surveillance system. So DA Henderson who later became the dean of Johns Hopkins, DA was in Geneva. He flew in, Halfdan Mahler, who was the Director General of WHO flew in, Mrs Gandhi came and we were about to do the first global television broadcast ever done. We all went to the television Studio, New Delhi television. And while we were there waiting for the camera to go on Mrs Gandhi, we got a telegram that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was the Prime Minister of Bangladesh had been killed.

0:22:11.5 DB: Wow.

0:22:12.1 LB: And with his assassination, millions of people were fleeing as refugees from Bangladesh and some of them were carrying smallpox and they reintroduced smallpox back into India. So we stopped the broadcast. Mrs Gandhi was extremely angry. Dr Mahler was not so happy having made the trip to India and we had to start all over again. I think that success is only sweeter when you've had so many roadblocks, this was a big roadblock.

0:22:42.1 DB: Absolutely.

0:22:44.4 LB: But the last case of smallpox, the last case of Variola major, now there's a lot of last cases, there's the last case of Variola major in nature, then there's the last case of Variola major from a lab accident, there's the last case of Alastrim or Variola minor. But the one that matters the most to me was the last case of Variola major in nature because that's the one that stretches all the way back to Pharaoh Ramesses V, an unbroken chain of transmission over those thousands of years.

0:23:10.8 DB: Wow.

0:23:11.5 LB: And that was a little girl named Rahima Banu and she lived in a village called Kuralia on Bhola Island in Bangladesh. And when we had finished eradicating smallpox in India and Nepal and Pakistan and Bangladesh alone was infected, we got a call, I was working at the regional office called SEARO, the South-East Asia Regional Office and we got a call that they thought that they had found the last case and there was a lot of, I don't know, wariness because we'd done that before. So I was asked to go and lead a team to do a search of 30 miles radius around that case and see if we can find more. We didn't find any more cases. And I was face to face with this little girl who was the last case of smallpox in my world and I thought that as her scabs had fallen on the ground and the virus was killed by the sun and she breathed out the last virus, she recovered. As those viruses died, that was the end of history, that was the end of all the stories about smallpox and all the number of billions of people perhaps who had been killed by it. I just cried like a baby. That's when public health is good.

0:24:29.2 DB: Absolutely. Absolutely. Absolutely. Remarkable feat and accomplishment and one that this conversation has illustrated still carries many lessons for us to think about future threats. So now I actually move to a related topic building on that remark, that one of the wonderful things that you did recently was to donate your World Health Organization India smallpox campaign archive to the University of Michigan's Bentley Historical Library. And so this includes tens of thousands of documents and photos and microfilms and CDs documenting the work of the team. And so I'd like to ask you what made you decide to make this generous donation to the University of Michigan? And then how do you hope that this rich resource is utilized?

0:25:18.0 LB: Well, it's a very unique archive. When I was teaching in Ann Arbor, DA Henderson asked me to go back to New Delhi and turn off the lights on the program. After we had found the last case, there was an obligatory two-year period of observation to be sure there were no more cases. That had expired, WHO had now declared smallpox eradicated, but the program, the office had not been closed down. So I went from Ann Arbor back to New Delhi and I closed down the office and in doing that, I asked to see all of the files and I said, "What are you gonna do with them?" They said, "Well, we're going to burn them.

0:25:52.6 DB: Oh, wow.

0:25:53.4 LB: So I called DA and he said, "Make a microfilm before they're burned." And so I tried to get the microfilming done in India, but the WHO files in those days, especially the carbon copies were on such paper, it couldn't go through these machines that they used in India. So I said to DA, "Shall I bring them to Geneva?" And I did. We couldn't find any place in Geneva that could handle such delicate paper, but there was a place in Ann Arbor and that place was called University of Microfilm. So I asked them if they could make these into microfilm? They said, "Yes, and on top of that we won't charge you because we know how historically important this is."

0:26:32.3 DB: Wow.

0:26:33.6 LB: So I took one set of the microfilm and I sent it to the WHO library, I gave one set to DA Henderson and I kept one set. And then I said to DA, "What should I do with the originals?" And there were hundreds of thousands of pages and photos and records and DA said, "Well, call up the library in WHO and offer them that." So I did and they said, "No, we don't want that. We don't have any space." So over the next 40 years, every few years, I would call up WHO and I would say, "What do you want me to do with this library?" And every time they would say, "Oh, we've got the microfilm, that's good enough." When I was at Google, I digitized the entire library.

0:27:14.4 DB: Okay, okay.

0:27:15.2 LB: And I thought that was enough. So I said to WHO, "Will you take the originals?" They said, "No." I called DA and he said, "Do whatever you wanna do with it." So I kept it with me for another 30 years and I moved it every time I moved, I took them with me, it fills up an entire room. And then I was talking to the folks in Ann Arbor and I said, "That's the right place for it." That's where the microfilms were made, that's where I was a professor, that's where I really learned epidemiology, so I'm really happy they're there. And I have to... Just a word, the Bentley is a treasure and the people there are just wonderful people. So I hope that everybody who is interested will be able to see whatever you want. There's a lot of great photos and a great movie. The only movie that I know of that has actual pictures of people with smallpox and the eradicators, it was a Japanese movie.

0:28:08.3 DB: Yeah, and thanks to you for having the foresight to really work hard to preserve those originals and share that. They ultimately found a home where they'll benefit generations to come. Your work in smallpox was of course not the end of the road, you closed one chapter, declared victory, but you knew there'd be work ahead and so I'd like to now ask you just about your experience working in the World Health Organization's effort to eradicate polio. How did you get involved in that work? And then what lessons learned from the smallpox campaign were you able to actually apply to address polio? And then the other side of the question is were there specific things that you had to do or go about differently?

0:28:57.9 LB: That tsunami, the Boxing Day tsunami in 2004, I think it was, when that occurred, I immediately got on a plane and I went to volunteer to work in the refugee camps. There were so many refugees in it. I saw the pictures of this train in Hikkaduwa in Sri Lanka that had turned over and Indonesia had so many people who had hurt, and hurt. So I started working in the refugee camps. And after I had worked for several months in the refugee camps and it was time for me to come home, I came back to New Delhi and I visited the WHO offices and David Heymann was visiting there from Geneva. He was the head of the polio program and he said, "Look, we've had a tragedy and the person who was running the program in the state of Uttar Pradesh had to leave. We don't have anybody running the program there. Would you do that for six months?" So I stayed for six months and we reorganized the program around similar lines. We started focusing more on surveillance. Now, it's not so easy with polio. With smallpox, 100% of the people have scars or lesions and it's very visible. Polio, only one out of a thousand people that are infected have any symptoms at all and those symptoms are very slow to be appreciated because they're of paresis and then paralysis. So surveillance had a very different meaning.

0:30:32.4 LB: We established a proxy for surveillance which is called Acute Flaccid Paralysis, AFP, and we began looking house to house again, looking for every case of a child who had any kind of paralysis, whatever the cause, even if it was transient. And we developed a benchmark and we looked at places that had a higher incidence than that benchmark. We also used sewage sampling for the very first time and looked at the genomics of the virus that we found. So we still had a surveillance lead vaccination program instead of just vaccinating everybody. I don't think people know that what slows down the polio eradication program in Pakistan is that these poor little kids don't have much of an immune system. They usually have two or three other enteroviruses competing for their immune system's attention and in order to give them immunity against polio, sometimes they get vaccinated, not once, not twice, but 20 times. And so the parents get really mad. They say, "Why are you Westerners only coming to my house just for this one disease? I have a lot of other problems." And it's a legitimate... Certainly, it's a legitimate concern. But I was really happy to be able to see the last cases of polio in India. There's still a handful of cases in Pakistan, but just as all the little articles you see about polio, we're this close, we're still this close and it's worth it.

0:32:05.8 DB: Absolutely. And so another facet of your very remarkable career is that following your work on smallpox, many people involved in that program including you and your wife came together to create the Seva Foundation, which of course works to provide critical eye care and to restore sight for people across the globe. And you've said at the time when you started doing that work and when you started the foundation in the late 1970s that blindness was thought of as a clinical disease, not a public health issue. Can you tell us why you decided to tackle this problem, and to do so as a public health problem?

0:32:46.0 LB: So full disclosure, I was a hippie and I first came to India with a caravan of psychedelic painted buses and I lived in an ashram for three years. It was my teacher in the ashram who told me that I had to go work for WHO and help eradicate smallpox. But after smallpox was eradicated, some of the Russian epidemiologists, American epidemiologists, WHO workers from all over the world wanted to do something like that again. My wife and I had written an article about how smallpox was eradicated and when the article came out, people sent me money, cash in envelopes and I knew I wasn't supposed to buy a Mercedes with that so I started the Seva Foundation and I brought all the people together, but I didn't wanna just bring WHO people, I didn't wanna just bring CDC people that had PhDs in epidemiology.

0:33:38.1 LB: I wanted to bring people who had a heart connection to doing work in the field for people who were less privileged and maybe had a political conviction of working with lesser developed countries. So the people I brought together for the board meeting were very eclectic. They didn't look exactly the same as the folks in the smallpox program, although Bill Foege was there, but I had Steve Jobs there and I had Wavy Gravy there and I had Ram Dass there and I had spiritual people from about 10 different religions, I think, maybe more. And we became the Seva Foundation. We also had Jerry Garcia and Bobby Weir from the Grateful Dead. And over the next 30 years, we've had over 150 concerts, benefit concerts, many of them by the Grateful Dead or the Jefferson Airplane, Joan Baez, some of them in Ann Arbor, mostly out here on the West Coast that raised $200 million to fund the blindness work. And I'm really proud that two years ago before Nick Kristof took a hiatus from The New York Times, every year he gives an award to the top non-profit, Seva got the Nick Kristof Award...

0:34:49.8 DB: Wow.

0:34:50.3 LB: For being the best non-profit, and I'm very proud of that. I'm very proud that 5 million people can see again and for free because of the money donated. Some of you folks met Suzanne Gilbert when she was in Ann Arbor. We hired her as our second employee in Ann Arbor and she's still running the blindness program. Great job.

0:35:08.8 DB: One notable thing about your career is you've worked in ways where you could actually see and observe the impact of your efforts and that has to feel very, very rewarding, thinking about many areas of science where one's advancements and contributions, they are making an impact, but the bulk of that impact is maybe many years ahead. So I want to transition now just bringing us really to the present to address COVID. You obviously have a tremendous of amount of expertise around pandemic response and disease eradication and for many years before the COVID-19 pandemic, you were talking about strategies that we can and should use to prevent the next threat and it's because you understood that the question wasn't really about will the next pandemic prone outbreak happen, but it was more of a matter of when. And so as you look back now, perhaps some of the things that you could anticipate as you were ahead of the curve, if you will, what are some of the things that you think we did right when it came to our COVID-19 response? What are some areas that reflect shortcomings or areas that we went wrong?

0:36:19.4 LB: One always wants to see the best, but I would say that our response to COVID was shameful. There's hardly any country in the world that could take great pride in the response that they had to COVID. Some countries prior to there being vaccines did extremely well. They were mostly the countries of Southeast Asia, Thailand and particularly Cambodia, Vietnam, Taiwan and then New Zealand. A lot of the island countries run by women did very, very well, I have to say. But once there was a vaccine and we can talk just for a moment about Operation Warp Speed, once there was a vaccine, the US gobbled up a disproportionate amount of the vaccine doses, the wealthy world, put advanced purchase agreements in place, locking up the supply. So countries like... And I'll focus for a second on South Africa. Countries like South Africa didn't get any vaccine and those things that were helpful to prevent the spread of COVID prior didn't work very well once the virus began to mutate, it became more transmissible. And I to this day think that the failure of companies like Moderna to allow proximate manufacture of their vaccine in Africa was one of the factors that has led to the creation of new variants, certainly Omicron, with all of its mutations. We have to be really careful. I think the Trump administration did awful.

0:37:56.6 LB: There was one moment when a cruise ship with 2000 people on it and hundreds of Americans with COVID was coming in to get those people medical care and Trump said, "I don't want that boat docking on an American port because then those numbers will count against me." And I still think that is the most shameful act of a president in history. It was all about those numbers. But I don't think the Biden administration's rollout has been stellar. I think Andy Slavitt did a great job in the rollout, but the disinformation, misinformation, missteps of my beloved CDC, where I trained as well, I did my residency in preventive medicine at Michigan and CDC, but CDC has been a big disappointment. I think there's a lot of credit that goes to the individual workers in the field, the county health officers, state health workers, but I think at a national level, when the final reports are made, we could have done so much better, we missed so many opportunities. And so that's something that brings me great sadness. I don't like to say that publicly 'cause the field of public health is already becoming downtrodden. We've taken all the flack and there's a lot of anger, misunderstanding of public health. I think we in public health did really well, but the politicians did terrible. And it's not just Republican or Democrat, right-wing or left-wing, almost all of them did terrible.

0:39:27.2 DB: I wanna build on a thread that you included in your remarks and asking about public health communications and you engage extensively in communications where in your role as a CNN medical analyst and you write articles for a number of different news sources, you're on social media a lot. Why is the area of communications important to the field of public health? And why do you dedicate a lot of your time in this space of communications?

0:39:53.1 LB: This brings us back to Bill Foege and these nine lessons from smallpox eradication. The number one lesson is that with public trust, public health can do anything. Without public trust, public health can't do almost anything. And we squandered public trust. Politician after politician failed to allow transparency and honest communications, alternative facts in the United States, but it was everywhere, it wasn't just here. Modi's India, Bolsonaro's Brazil, there were very few countries that maintained open, honest, transparent communications. If you don't tell the truth, it may be a short-term winning strategy, but long term, it's a terrible strategy. It's morally corrosive. You bankrupt the bank in which trust is stored and once it's gone, it's very difficult to restore it. And that's one of the lessons from smallpox eradication. Radical transparency, honest numbers, full reporting and especially the mistakes that you make. Say them first, be honest about them, and humility.

0:41:07.6 DB: Yeah, absolutely. So now we're entering a new phase of the pandemic where we're learning to coexist with COVID, but as we're experiencing now, we will face formidable new variants and as we look toward the future though, there'll also undoubtedly be other disease threats that we'll face in the future. Keeping all of your remarks in mind about how we handled the emergence of COVID, what should we be thinking about in terms of pandemic preparedness now for the future?

0:41:41.7 LB: So I have an article in the current issue of Foreign Affairs trying to analyze what the next big one might be, more to say these are things you don't have to worry about, they're not gonna be a big pandemic compared to what we have now. And mostly respiratory diseases with short incubation periods and high reproduction numbers, which really takes you down to coronaviruses and influenza viruses. But it may very well be that the next pandemic is not another virus, but it's actually just SARS-CoV-2. We now have over 500 variants and sub-variants of this disease. It may be just because we have genomics now and we're looking for it that we know. There maybe other viruses, RNA viruses have had that many variants. It's hard to believe that that's the case however. So 500 sub-variants means either one of two things. One, this would be good. And [0:42:39.3] ____ is the king of Corona cold viruses. We have four of them. Half of all the colds that you get are coronaviruses and they look enough like COVID to make you imagine that perhaps 500 years ago there was another COVID pandemic and that these old coronavirus pandemics have now retired into the retirement home called... They became a cold.

0:43:08.2 LB: And it may be that having 500 sub-variants is a signal that this one's running out of gas and that there are very few more mutations left to be had on the spike for example. It may not be though. I have some very good friends who are evolutionary virologists. They're certain that this is the end, the swan song, the denouement of COVID. I pray that they are right. But I'm a mathematical wonk and I look at the 1.4 billion people in China, I look at vaccines that have 20% to 30% efficacy, I look at the fact that less than 100 million people have had the disease, there's probably one billion people in China who are immunologically naive to either the XBB.1.5 that we may be sending to them or to the BA.7 which is currently prevalent in China. And I can't imagine what's gonna happen after Chinese New Year's if as many people get COVID as the models show in a shorter period of time. So I think it's a low probability that we will get a super bad variant out of COVID at this stage, but it's a low probability with a highly consequential event, and I don't think we're paying it enough attention.

0:44:26.8 DB: Right, right. You've spoken about optimism in the phase of your work. What keeps you optimistic as... You've confronted challenge after challenge after challenge?

0:44:37.3 LB: Well, I've met Martin Luther King and I've seen the last case of smallpox and I had a guru in the Himalayas who predicted that smallpox would be eradicated. Those are all impossible things for a kid from Detroit, Michigan, so how can I not be optimistic?

0:44:51.5 DB: Yeah, yeah. Terrific. So we've covered a lot today. I think it's evident from this conversation and from what you've written including in your book that you've constantly pushed yourself to explore new experiences and to be open-minded and honestly courageous when it comes to your life and your career and thinking about our audience that will surely include some students and young professionals, can you talk more just about the value of that and what you would say to others in this regard as they go about continuing their educational journeys and their careers?

0:45:30.3 LB: So I've had another life, of course, in the technology world. I was Vice President of Google and I've run a bunch of tech companies and I've been around a lot of wealth. So I've been around a lot of success and that meaning of success and around a lot of success in the world of public health. There's no comparison. You may be wealthier being in business, but yet you won't be happier. The happiest people in the world are the people who've worked for others, sacrificed themselves, worked in public health, often thankless, but they know, we know what you've done. It's the most rewarding field in the world. And if your goal is to be happy and to feel at the end of time that you've done as good a job with this life that you've inherited, you can't go wrong with public health.

0:46:23.8 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. So we're just about now at the end of our time for Ahead of the Curve and I wanna express my sincere thanks and appreciation to you Dr. Brilliant for taking time to be with us today and for sharing some really great insights and remarkable stories and stories that reflect many lessons for leadership. Larry, thank you so much again. I've learned so much in our conversation today. I know and trust that members of our audience have as well and so I just wanna again reiterate my appreciation and thanks to you for joining us. So be well, stay safe and always go blue.

0:47:01.4 LB: Go blue, and DuBois, I've had the privilege of working with and knowing seven deans of the School of Public Health. I hope they know how lucky they are that they have you. Thank you.

0:47:12.0 DB: I really appreciate it, really appreciate it. Thank you.

[music]

Dr. Larry Brilliant is a physician and epidemiologist, CEO of Pandefense Advisory, senior counselor at the Skoll Foundation and a CNN Medical Analyst. Previously, he served on the board of the Skoll Foundation, was Chair of the Advisory Board of the NGO Ending Pandemics, the president and CEO of the Skoll Global Threats Fund, vice president of Google, and the founding executive director of Google.org. He co-founded the Seva Foundation, an NGO whose programs have given back sight to more than 5 million blind people in two dozen countries. In addition, he co-founded The Well, a progenitor of today's social media platforms.

Earlier in his career, Dr. Brilliant was an associate professor of epidemiology and international health planning at the University of Michigan. Dr. Brilliant lived in India for nearly a decade where he was a key member of the successful WHO Smallpox Eradication Programme for SE Asia as well as the WHO Polio Eradication Programme. He was the founding chairman of the National Biosurveillance Advisory Subcommittee (NBAS), which was created by presidential directive of President George W. Bush, he was a member of the World Economic Forum's Agenda Council on Catastrophic Risk, and a "First Responder" for CDC's bio-terrorism response effort. Recent awards include the TED Prize, Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People, "International Public Health Hero," and four honorary doctorates.

He has lectured at Oxford, Harvard, Berkeley and many other colleges, spoken at the Royal Society, the Pentagon, NIH, the United Nations, and some of the largest companies and nonprofits all over the world. He has written for Forbes, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, and other magazines and peer reviewed journals and was part of the Global Business Network where he learned scenario planning. Dr. Brilliant is the author of “Sometimes Brilliant,” a memoir about working to eradicate smallpox, and a guide to managing vaccination programs entitled “The Management of Smallpox Eradication.”