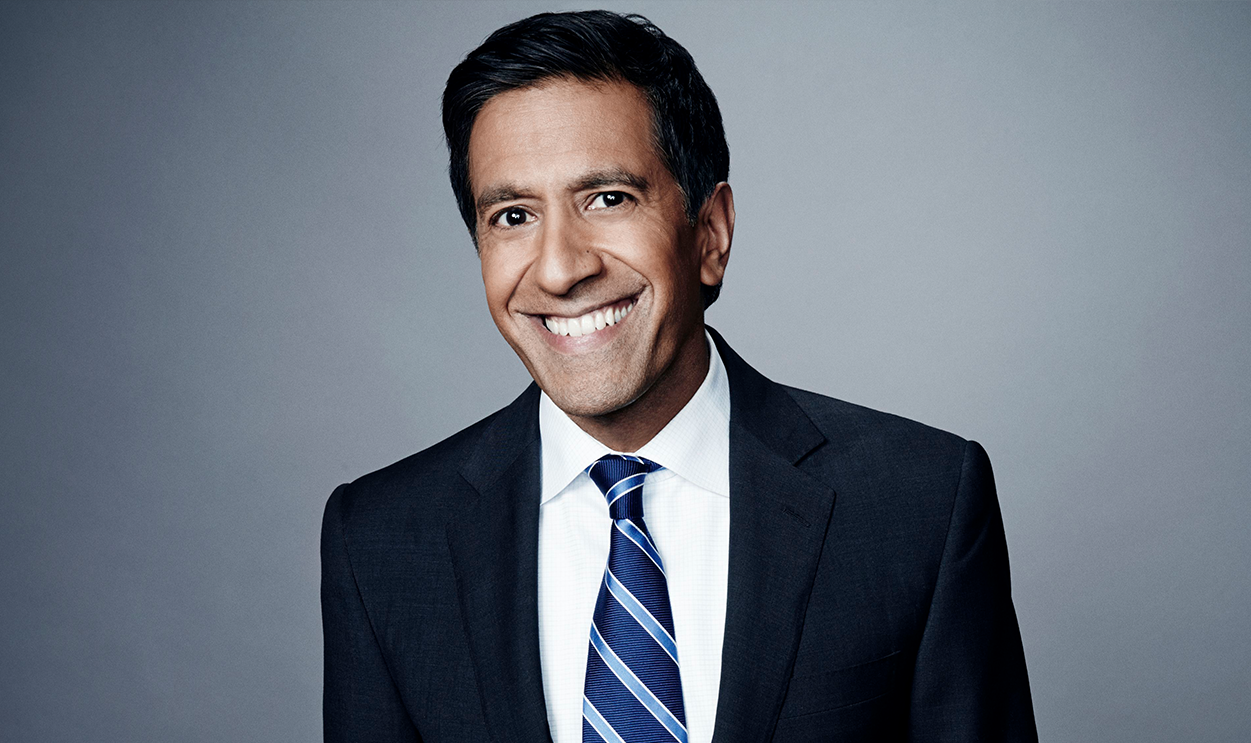

Ahead of the Curve featuring Dr. Sanjay Gupta

February 1, 2023

Ahead of the Curve featuring Dr. Sanjay Gupta

Watch

Listen

Listen to "Ahead of the Curve: Sanjay Gupta" on Spreaker.

[music]

0:00:11.1 DuBois Bowman: Thank you for joining us for Ahead of the Curve. It's a speaker series from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. My name is DuBois Bowman, and I have the pleasure of serving as Dean of the School of Public Health. The Ahead of the Curve speaker series focuses on conversations about leadership, and throughout the series, we have discussions with contemporary leaders across different sectors in the health field, to hear about their insights and their vision and stories of perseverance. Leadership is a critical component to navigating complex health challenges and building a better future through improved health and equity. We wanna hear about the important factors that shape great leaders, we also wanna learn about how they continue to evolve and grow, so that in turn, we can think about how to best train the next generation of leaders. We have a fantastic guest with us today to explore these issues, I'm delighted to welcome Dr. Sanjay Gupta, the multiple Emmy award-winning Chief Medical Correspondent for CNN, as well as a practicing neurosurgeon. Dr. Gupta plays an integral role in CNN's reporting on health and medical news for all of CNN shows domestically and internationally and regularly contributes to cnn.com. He's covered some of the most important health stories in the United States and around the world.

0:01:33.8 DB: Over the last few years, Dr. Gupta has increasingly focused on long-form reporting. He is the host of CNN's original series, Chasing Life, and he's been involved in several documentary films. And in addition to his work for CNN, he's an associate professor of neurosurgery at Emory University Hospital, and the Associate Chief of Neurosurgery at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. And we're very proud to say that he's a University of Michigan alum. Dr. Gupta received his undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan and a Doctor of Medicine from the University of Michigan Medical School. I'm really excited about the conversation, and I wanna thank all of those who submitted questions at the time of registration, we really appreciate receiving those, and we had a lot of questions about communications, combating misinformation, building trust, and we're gonna try to work a lot of that into today's conversation. So Sanjay, if you're ready to kick it off, we can go ahead and dive in.

0:02:38.5 Sanjay Gupta: Yes sir, Dean. Ready.

0:02:40.4 DB: So, let's start just with a few questions about your background and training, which as noted, began right here at Michigan. And just for starters, what made you decide to study medicine? Was this a field that you always knew that you had interest in, or was there a turning point at some point throughout your educational journey?

0:03:00.0 SG: It started at a pretty young age for me, I think I was in my early teens when I decided to do this, to... Started really thinking about being a doctor. There was no one in my family who was a doctor. My parents were both engineers. And I think that there is this idea that I was gonna go into engineering by way of mathematics like my dad did or something like that, but I really fell in love with medicine. My mom's father had become ill when I was around 13 years old, and I was spending a lot of time with him in the hospital asking a lot of questions probably, but getting an idea that that could be a profession. And I think I was sold at that point in terms of wanting to be a doctor. Figuring out what kind of doctor to be, that came much later, but I think around early teens, probably.

0:03:44.5 DB: Terrific. And over the past couple of weeks as we've advertised for today's event, multiple people have come up to me on campus with stories about their memories of you while you were here on campus, and some of these were based on interactions, as I understand as your time as the residence director at... [0:04:03.1] ____.

0:04:03.2 SG: Oh no. [chuckle]

0:04:03.2 DB: Or similar positions at West Quad. And what I sense from all of these interactions was just the general and genuine fondness and high regard that these individuals have for you, and that's you as a student at the time. Before the days where you became the highly esteemed invisible public figure. And so from your perspective, as you think back on your time here at Michigan, what was your experience like? And what were some of your fondest memories?

0:04:37.4 SG: I gotta tell you... Just broadly speaking, Dean, I've had a chance, and I think when you have the perspective of time, I'm in my early 50s now. Like you, I've been to a lot of places, and part of a lot of different institutions, and this is a broad answer to your question, but I think there's something about Michigan that is just so pervasive and it gets under your skin, so to speak, in a very good way. And I think that there's just a connectedness when you see people from Michigan out and about and I have lived in different parts of the country, if they're wearing a Michigan shirt, a Michigan hat. There is a... I see that with other universities as well, but with Michigan it runs deep. It runs really deep, and I think because the alumni base is so large and so global that I travel around the world, and Michigan people... I was covering a war in Iraq, and the helicopter pilot that ended up evacuating me out of this pretty dangerous situation was a Michigan grad. We talked Michigan football as we're flying over a battlefield in Iraq.

0:05:37.9 SG: I have a lot of fond memories. Obviously, the big ones, the games, the seminal events. I was there for the Fab Five. I was there for these big things, but I think... Like I think a lot of people who may be approached too, it was a smaller events, it was a chance meeting with somebody at the law library that became a life-long friendship, dinners out. Just those sorts of things. It was one of the most idyllic experiences, times in my life.

0:06:04.1 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. As you think about your time here at Michigan, how did your training here, how has it helped to serve you throughout your career?

0:06:14.5 SG: I've thought about this quite a bit, and I think there's lots of ways. Obviously, when you spend as much time in the university, in the medical school and even my training there, there's all these different exposures that I've had that have had a significant influence. But I think I'd answer almost in a little bit of a counter-intuitive way, Dean. I think that when you have a place like Michigan that is the size that it is, but also excels in so many different areas, I think when you're starting as a student, even though I was pretty sure I wanted to be a doctor, I knew that, to have these other exposures, took me into these different areas of my life. I really do attribute initially my interest in healthcare policy, but then subsequently journalism and investigative journalism, two experiences I had as a student. Even though I did not act upon them right away, I was doing my neurosurgery residency and things like that. I had that exposure and then subsequently developed a real passion and interest in these areas. So that was, I think very instrumental in how I've crafted my own life.

0:07:12.7 DB: Yeah, such a tremendous asset, the breadth of expertise available across the University of Michigan. Often we select institutions for rather local reasons of going to a specific department that has expertise, but all of the stuff that comes with it at the University of Michigan is such an incredible bonus and a luxury to have. So you commented on even early seeds, if you will, that piqued your interest in journalism. So you completed your neurosurgery residency in Michigan Medicine in 2000, and then you joined CNN as a correspondent in 2001. So throughout the majority of your career, you've been practicing both as a neurosurgeon and serving as a journalist, and so how did you get into journalism? Similarly, was it a field that you knew that you always wanted to pursue even while you were in med school? And if so, how did that impact your perspective about how you viewed your medical education or possibly even your approach at the time?

0:08:14.0 SG: Yeah, I would say that there was a serendipity about this, Dean. It's interesting, so I did have an interest, I think, in communications and journalism under that larger umbrella. I became very interested in healthcare policy when I was a resident, it was a pretty simple reason, there was a lot of discussion happening around healthcare policy, this is the mid-late 90s. And clinicians really weren't as large part of that conversation, and I just thought that the people who are working in hospitals, caring for patients, doing medical work and public health work, should be a part of the conversation. So, I started doing some writing around healthcare policy issues, some very specific topic sub-specialty reimbursements, but also looking at health outcomes data for the United States compared to 14 other similar countries and just started doing that. I took a year during my neurosurgery training to go work as a White House fellow, where I primarily wrote and worked on these same issues working for the First Lady at that point, and that was Hillary Clinton. This was '98. '97, '98. Came back to Michigan after that and had that bug, I think, a little bit. I moved to Atlanta to take a job at Emory in neurosurgery, and when I started doing CNN work, it was more that the idea that I was going to be a commentator on healthcare policy issues for some of the Sunday morning shows, things like that.

0:09:37.1 SG: Really that background. But what happened, Dean, and this is the bizarre part of the story in a way, is that everything changed, 9/11 happens, and that's just a few weeks after I've started working here. And basically, they say we're not gonna be talking about health policy probably for a while given the events of the world. You're now a doc at an international news network, would you like to tell some of those stories, report on some of that? And I thought it would be interesting. That was it. That was the inflection point.

0:10:06.6 DB: It's fascinating, the serendipity that you mentioned. But also to credit you for the courage to chart your own path, and oftentimes as we seek guidance from those who have gone before us, they tend to reinforce certain standards or norms in a discipline or field, it must have been insightful of a... You're still young, but even a younger version of you, to be able to tap into your own passions and your own talent in a way that certainly has served us all well.

0:10:38.0 SG: You're very kind to say that. I think the one lesson I would say in all that was that you keep your eyes and ears open, and sometimes people look for the best job to... Before they'll think about taking that job, it's gotta be perfect. And I think being on the ground, so to speak, just getting on the ground, in the door, however you wanna phrase it, frame it, is important. I love journalism, I wasn't going to do this kind of journalism, it was again, supposed to be mostly commentary on specific areas of health care policy. It was the first year of a new president at that time, George W. Bush, what was the healthcare plan going to be? That was what I was going to do, then the world changes for everybody.

0:11:17.8 DB: Yeah. And so the world changes, you are in really high demand for your expertise on the journalism side, and then you flourish into a national figure, why did you decide to continue practicing being a neurosurgeon given the pulls and the time demands on each side?

0:11:37.8 SG: It's funny. It's a good question. I will say that my mom still asks me sometimes, "Are you still doing that TV thing that you do?" [laughter] I don't know, I'm not saying the answer is to please my parents because that should not be how it's interpreted, but I would say that, I think part of the reason I continue practicing neurosurgery, honestly Dean, I love it. I really love... I love being a doctor, I love neurosurgery, and there's lots of aspects to that, I love the science of the neuroscience, but there's a technical aspect to it, almost an athletic, if you will. And I don't say this in any way to minimize the field, but I'm saying that you get attracted to these athleticism of it, the movement part of it. I love the fact that when I'm in the operating room, you have this very defined time where I just get to focus on this. I feel like the world is such a distractable place, there aren't many places in our society anymore where you can just totally dig in, focus on one thing and operating on the brain is one of those things, for sure. And so it's that, I think that is... There's lots of reasons that I continue to do it, but I think the biggest one is that I love it for all those reasons.

0:12:44.1 DB: Certainly, your training and experience as a neurosurgeon benefits to your career in journalism from a substantive perspective, but more broadly speaking, as you find yourself spanning these two very different worlds, do you find other synergies, are there things that you find in your journalism career that somehow contribute to your clinical work or vice versa? The clinical experience somehow contributing beyond the substantive knowledge to the work that you do as a journalist.

0:13:14.3 SG: Yeah, absolutely. I think one thing that maybe it goes without saying is that when you're a medical correspondent for a large news network, your breadth of knowledge has to be pretty great, so you have to be pretty wide in terms of how you're thinking about things. So I'm reading lots of different things, that's my main input. I'm reading the journals, I'm also talking to lots of people within certain fields, not just neuroscience, neurosurgery, and I think there's always things that you learn from a particular field that can apply to other fields. And I think you think about who are those people who travel back and forth a lot of times it's people like you, academics who are interacting with people from all these different disciplines, but I think journalists do that as well. So there is a lot of that shared knowledge that I can sometimes see the connective tissue between things that is quite useful.

0:14:06.3 SG: I will say almost on a philosophical level, journalists are all about telling stories and medical people and public health people, we are exposed to the greatest stories on earth constantly. Stories of people, stories of populations, stories of people overcoming some adversity, triumph, all those things, and yet I think sometimes it surprises me. Even me when I was in neurosurgery residency, it's so procedural, your job, and sometimes you forget just how incredible the stories are. And I think the journalism part of my life has reminded me of that. It's added a joy to medicine in a way, because I get to spend more time really digging into the stories and enjoying the stories, and my residents all know how to present a patient to me based on story, so it goes back both ways, there's been a lot of benefit both ways.

0:14:55.4 DB: Yeah, yeah, that's fascinating. You noted 9/11, but over the years, you've reported on many high profile events and issues that have clear public health impacts in addition to 9/11, things like Hurricane Katrina, the war in Afghanistan, climate change and natural disasters, etcetera. I imagine, and you can walk me through this, but I can imagine that in many instances when you begin reporting, you don't yet have all of the information. You begin you're reporting by sharing what's known at the time, but there are a lot of questions and maybe even sometimes, gaps. And so what's your approach to communicating about topics like these, and how do you try to build trust with an audience when a situation that you're reporting on is still rapidly evolving, and there still are so many unknowns?

0:15:45.1 SG: Yeah, it's a great question, Dean. Different sorts of stories that you mentioned there, but when you're talking about natural disaster, for example, Katrina or the earthquake in Haiti for example, we are oftentimes, journalists are on the ground before anybody else, sometimes even before relief, certain relief workers, either governmental or NGOs are on the ground. Sometimes we already have a presence there, but whatever the reason. And so being that you're the first in that period of time when there's not a lot of details yet, and the world is just starting to see something unfold, there's been an earthquake in Haiti, details are coming in slowly. Just basically, frankly, less talking and more allowing people to see the visual images of the story that you're telling and just describing it for them, recognizing that this is not the time to start speculating in what, why, where, things like that because you're just catching everybody up to what has happened here. These buildings have come toppling to the ground, that's closed the streets, people cannot move from point A to point B, relief workers can't get in. Whatever it might be. Just describing the scene, I think is really important.

0:17:00.6 SG: I will say that there is a parallel, again, as you were asking, between medicine and media, in that it becomes clear at some point, people do want... They're gonna start asking questions that you cannot yet answer, and I think patients do this to doctors a lot. Doctor, what does it all mean? How am I gonna do? What's this diagnosis going to mean? And we live in a probabilistic world, so doctors say, "Well, it could be this, this, and this," but they start to lay out things. They don't know yet, but they're starting to lay out the possibilities, and I think journalists sometimes do that as well. But I think in both situations, you just have to be very transparent. We do not yet know x, y, z. But here's what we're starting to hear, here's what it's looking like, we're gonna confirm some of this. There's a reason I think doctors are very trusted, and I think some of those same basic skills I'm talking about in terms of communication style, there's a relation to journalism as well in terms of how those types of communication techniques should be used.

0:18:00.6 DB: Remaining on this theme for a moment of evolving information, you just drew parallels between your work in the journalism space and then in the medical space, but I would also add to that even more broadly, the scientific process. A study comes out that tells us one thing, sometime later, additional research is done that sheds light in a way that refines, possibly even contradicts our prior understanding, and so you mentioned a word, transparency. Often we work to try to complete the story before we begin telling it. And so how essential, and how does one go about achieving that transparency but still remaining squarely in your area of expertise where you still come across as an authority on a topic?

0:18:48.9 SG: Yeah, I think that this is... This really cuts to the heart, I think, of what medical communication is all about. And again, I'll take the privilege of speaking to someone like you and lean into the nuance a little bit here. There is this idea sometimes, and if you look at polling data, that scientists and clinicians and people even in the medical, public health world have been increasingly perceived as arrogant, and that predates pandemic. These polls have been going on for some time. One of them was done at University of Michigan, actually. And I always thought that was interesting. And I think it's one of those things you have to take note of. Whether or not you agree with it, you have to say, "Well, that's interesting that people in this field are increasingly perceived as arrogant." But here's the point that I'm making is that, for example, during the pandemic, I heard people oftentimes saying something like, "Trust the science and believe in the science, have faith in the science." And sometimes it felt very much like there was a conflating with religion, almost. And I just think that the scientific process is the story, not trusting the science. The scientific process is the story.

0:19:58.3 SG: There's a great story to be told, kinda like I was saying about medical journalism in general, but here's what they decided to do. They took 800 people. They gave 800 of them this thing. They gave... 800 did not receive this. But this is what they received. And they followed them, just explaining it. Because we live in a probabilistic world. People want certainty. I get it. I want certainty too. But I think the minute you start to try and fuel something with certainty when you don't really have the ability to do that, it is the genesis, I think, in some ways, of mistrust. So what are we really certain of in life, Dean? I mean what do they say? Death and taxes, right? During the pandemic, I'll just tell... I don't wanna talk too much. But I read Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, and that's how bored I was at times during the pandemic. But one of the things he says, and this is going back to the 1800s, early 1800s. He says that he thinks one of the greatest ills of society is an ignorance that we live in a probabilistic world, the idea that we all wanna see black and white where we should rightly see grey.

0:21:08.8 SG: And I just thought that was so interesting, even back 200 years ago, that he was saying this. That we want certainty in all that but that's the greatest ill of society, he said, is to pretend that we don't live in a probabilistic world. So there's a lot of components, I think, to dealing with restoring trust and addressing miscommunication. But I think one of them is that honesty and that humility that comes with it, that this is a story I'm telling you, the scientific process story. If you wanna ask me what it all means, like a patient might ask the doctor. "So what would you do?" They ask often in a visit. "What would you do, then? What if it were your mother?" I think it's a fair question. But at that point, you've changed the nature of the communication. Now it's become clear I'm telling you what I would do based on the same information, but I've told you the information you need to know to make your decision. And I think that's the story of the scientific process.

0:22:01.2 DB: Absolutely. Yeah, and wonderful story and examples as well, and even as you articulate the statement that we heard a lot about trust the science. For those of us who are in scientific fields, who do trust the science, that's trusting the science with all of its uncertainties and the ability to navigate the uncertainty, to weigh the evidence, the pros and cons, the risks and the benefits, and then ultimately come to a decision. And so I think a lot of that is lost, that nuance is lost in simple statements like, "Trust the science."

0:22:42.5 SG: Right.

0:22:44.7 DB: I'd like to just ask you to elaborate a little bit more on your experience during the pandemic. And as we talked about, this is a clear example where there was so much new. There was so much unfolding. There was so much that we didn't know at the beginning when you began your reporting. And can you just talk us through what that was like? And one of the things that we've heard is sort of a perception sometimes of having experts flip-flop. Again, it reflects more the natural progression of science. And so can you just talk us through how you approached and navigated that period of great uncertainty?

0:23:24.6 SG: Sure, yeah. It was, certainly from a public health standpoint, the biggest story I think that we covered during my time at CNN, just truly global, long timeframe, story still ongoing. I think in the beginning... One thing I would say, first of all, is that our beginning, meaning as medical reporters, is a different beginning, I think in some ways, than everyone else's. Because I'd covered many different outbreaks all over the world. I was in West Africa for Ebola, but I covered H1N1, H5N1, Zika, all these things. And I'd covered... We talked about MERS and SARS even back to 2003. So we had talked about not only outbreaks in the past but specifically even Coronavirus outbreaks. We're sort of approaching it from that background, new virus that's emerging, seems to be causing pulmonary problems primarily in people, clusters. And here is a good example. When we started, we were one of the first to say, "Look, this appears to be spreading human-to-human." That was something that was not being validated in China. The Chinese government was disagreeing with that at the time.

0:24:36.0 SG: But when you looked at the paper, for example, this gets back to the scientific process, you saw that there was an original... I think it was 21 patients, 21 people in the cluster that were affected, but they were from seven different households. So what does that mean? Did they all go to the same place? Or is it possible somebody came back, and then the people within the household were contracting it from that individual. We wanted to explain person-to-person transmission. So I'm just giving you an example of how we went about doing it. Here's why we think this may be spreading person-to-person and not just from animals to humans, as was initially thought. So I think it was that sort of process all along. But to your point, I think it was challenging because there were times when statements were made, I think, such as the vaccine prevents transmission of the virus, for example. And I thought, even at the time, it was too didactic. First of all, there wasn't an expectation, necessarily, that the vaccine was gonna prevent transmission. Yet almost the way it was presented was this was sort of the gravy on top sort of thing from the scientists.

0:25:42.0 SG: I think you have to be careful with that sort of thing in terms of being too certain or too definitive. And I think maybe the same thing even regarding masking, as you and I were talking about before it even started, I think just to be really clear on what it can and cannot do. That was a bit of a problem overall, I think, in terms of how these messages were communicated. Two things that I would put at the top of the list were not being clear that... It was kind of like you were having the end of the conversation with the patient in the room. Here's what you should do. But it took a lot to get to here's what you should do, and I only answered that because you asked me. What I wanted you to do is take all this information, and you think about what you should do. But it was all like that didactic part. And the second thing I will say, and this is my own thoughts on it more than anybody else I think, is that for both administrations, many of the scientific briefings are coming from the White House. That was not how it used to be, like during Ebola or when Rich Besser was talking about H1N1.

0:26:40.6 SG: It was always a scientific person, CDC Director typically, getting up in front of the CDC saying... Starting off by saying, "4000 of some of the smartest, hardest working scientists, dedicated people are in this building behind me. And I've been speaking to them, and here's what we know, and here's what we don't know." That's how Tom Frieden and Rich Besser and people like that approached it in the past. I thought it worked really well, and the trust was not eroded. I think when there was a co-mingling of politics and public health, by virtue of the very structure from which some of these messages came, I think that was problematic as well. So that doesn't really answer your question about how you deal with constantly changing information. But I think no matter the situation, if it's changing or it's not changing, if it's coming from a place of trust, sort of dealing with the fundamentals of the messaging first, I think helps at least blunt some of the bad perceptions of the information later.

0:27:39.0 DB: Yeah. And I think moving forward, we have to really hone in and focus on that element of trust, and that starts before an emergency ever arises. So hopefully that's a lesson learned that we'll keep in mind and make it stronger for the future. So I'd like to... As I think about your journey and this space that you feel connecting again, medical and scientific world in the space of, broadly of health communications, how do we produce more people who are able to contribute to that space? I think about our students, our faculty. In the "we" I'm thinking of institutions of higher ed, so academia broadly. And one of the things that I was proud to learn, that in 2018, the Gupta family sponsored a hackathon for health communication, in partnership with the University of Michigan's Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation in Michigan Medicine. And the students involved spent three days developing new potential solutions to problems in health communications. So I wanted just to ask, from your perspective, why did you choose to sponsor this event, and why do you think it's important for students to focus on health communications?

0:28:58.7 SG: My wife and I, Rebecca, were really honoured to do that. I think there's lots of reasons to do it. One is that we love Michigan, as I think I've made clear to you. I still, after all these years, consider Ann Arbor home in many ways. And Michigan, just it's the place where I feel comfortable and hang my hat. So we wanna contribute to Michigan, I think, in various ways. And one of the things that I noticed when I looked around the country is that training health journalists, there aren't a lot of programmes that do that, and there's not a lot of programmes that are really dedicated to it. I think that Michigan certainly, for all the reasons we talked about earlier, has all the resources to do that. And I wanted to do something that would create some interest around this area, so a hackathon around health communications. And when Rebecca and I were talking about it, we realised, what does that even mean, health communications? I think that means different things to different people. A journalist is an obvious one, but there's all sorts of different ways that people are communicating health, health material, health content. There's all sorts of different ways that people are intervening in people's lives using technology. People are looking at Apps that can measure your zygomatic activation to determine just what your sentiment is at any given time, and intervene if your sentiment is not good.

0:30:19.6 SG: It's fascinating to me. And I thought who better to, frankly, selfishly, teach me about all this than Michigan students. So hackathon... We're not even gonna tell you what health communications is. Come to us with 50 ideas. I think there was 50 presentations in the end. And we were just excited to learn. We invited people from industry to come as well, who might hear an idea there, and I think there's been some follow-up since then. But somebody might hear, "That's a fantastic idea. We run a health communications company," or, "We run a social media platform. Lets do something right away." That was exciting to see. But that's it. And we'd like to continue doing that sort of stuff, Dean, where hopefully, ideally, there is a health journalism field of study dedicated to this health, public health, scientific communications and let the students define what that means exactly. And I think that there will be plenty of jobs and desire for those types of people who are trained that way.

0:31:19.5 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. And as there's a proliferation of sources of how we receive information, I think it will be increasingly important to have people who are well-trained in this space to serve, to be able to help to communicate this important information to the public.

0:31:41.4 SG: It's funny, when you work in cable news... And again, I thought I was gonna be doing Sunday morning talk shows. You show up, and you think that you're gonna have some sort of session on what you should do, like where you should look or should you lower your voice, whatever it might be. And there's nothing like that. I remember I showed up there, and the guy was like, "I'm gonna put the mic right there." And that was it. And maybe this goes without saying, but some of my best learning has come from, in many ways, I know what I wanna say. I know the message that I wanna give. I know the content. I'm doing my homework. I know that. It really becomes a question of how to say it. And I happen to have three teenage girls. And I say this with some degree of humour but also great honesty, in that I would often try my messaging out on them before I would do it on television, and my wife.

0:32:33.4 SG: And it's interesting to have that sort of trial group because I think we can get pretty insular in medicine, thinking, "This is how I'm gonna say it." And then you go and tell your wife. She's like, "I have no idea what you're talking about it. You lost me at 'The.'" So it's a really simple piece of advice, but when you wanna... You've gotta spend some time on crafting the communication. I think people, they don't pay attention to actually working on that part of it. You get the content right, for sure. That goes without saying. But to actually say out loud your message a few times, and if you can, say it out loud to somebody who you trust and will be honest with you. I don't know. That may be a really simple piece of advice, but it served me well over the years.

0:33:20.4 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. And sometimes in your work, you, in your reporting, you serve as the medical expert. And there are other times where, to complement that role, you will bring in other outside experts to contribute to the reporting. And so why is it important that we have scientific medical and public health experts who are willing to speak to the media?

0:33:49.1 SG: I think that's part of building that trust again. We want to see people who've contributed to the science in some way, somebody who might be an epidemiologist or a vaccinologist, or whatever it may be. I think those voices... I've always thought those voices are really important, especially during something like a pandemic. I really pushed for that, to have as many different voices out there as possible. And I didn't have anything to do, by the way, with who those people are or were because there's almost a church-state sort of relationship there. I'm not trying to pull in a bunch of people who have a particular point of view on an issue and sort of stacking the medical journalists with a very specific point of view. So that was all done separately from me, but I thought the types of people we should have were really important. I think it's a better sort of thing for the audience. You're gonna hear from somebody who actually makes the vaccine, somebody who's studied outbreaks in other countries, who understands the value of whatever these social factors might be and how it's played out in other countries. We had historians on. Howard Markel, who's at Michigan, I had on several times to talk about issues that I thought were important. So that was basically it. We wanted to really make it as robust and broad an experience for the viewer as possible.

0:35:11.6 DB: I'm glad to see, at Michigan and academia as a whole, more attention paid just broadly to public engagement. But included as a specific example, media appearances where, for junior faculty who are early in their careers, there was a time where perhaps people were cautioned against spending too much time doing that kind of work. But I think that's detrimental to the public, right? It's detrimental to this rich resource of expertise that we have at the University of Michigan. We need to make sure that we're on the forefronts of getting that out there. So I'm glad to see positive trends in that direction.

0:35:48.4 SG: You know, if you look at some of the material, some of the topics that are covered in the news at any given time, they're going to be covered, right? They will be discussed. They are newsworthy. And I've always come from the school of thought that it should be the people who are the subject matter experts talking about that. I realise that sometimes it is hard for people who are subject matter experts to then go and talk about this to a broad audience via television. But somebody else will do it, so it should be you. I really do believe that. I'm not talking about anybody in particular, but I think that's really important. I will say that, going back to what we were just talking about a few minutes ago, sometimes there's a trepidation about it, sometimes there is a worry that my words may be taken out of context or something. And yeah, I mean I'm not naive. I realise that those types of things can always be a concern. Frankly, they can be a concern in a one-on-one conversation that you have with somebody. But that's where the practise comes in, so you learn how to work on the messaging of it so that it's as clear as possible and leaving less room for incorrect interpretations.

0:36:51.3 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. So we spent some time earlier talking about the sheer experience reporting through COVID. Lessons learned. If we had the ability to reverse the hands of time, or if we sit here and you're looking back, what are some of the things that you think we got right, perhaps, in the communication space? What should we be prepared to do differently in the future?

0:37:20.0 SG: Yeah, I think there's gonna be a lot of lessons learned, to be honest. We went through something that for most people alive today, almost everybody, we had never gone through before. And I think that there was a sense of how things would play out. And I think in many ways, it was very different. The United States was ranked, according to the John Hopkins National Health Index, before the pandemic as being the country most prepared to handle a pandemic, and that certainly did not play out in terms of numbers of cases and hospitalizations and deaths. And some of that I think is the communication issue, I think that that contributed to it. It wasn't the only thing, but I think that that contributed to it. A couple of things I mentioned earlier in terms of maybe lessons learned, I think one of them is you can't disentangle anything from politics nowadays, especially. But I think there was an entangling of public health and politics very early on, and just simply with the briefings even coming from the White House.

0:38:15.1 SG: Well, let alone that the President of the United States was then running these briefings for a period of time. And I will say just from the outset, both administrations did this. Biden administration also did these briefings from the White House, and I think there was this co-mingling. I think there were a lot of reasons for that. Some of them may be more justified than others, but ultimately I think that that may have been a seed of distrust. It became a political issue, and right away you're gonna have half the population essentially not liking some of these messages and half liking it, which that's a problem.

0:38:49.8 SG: The other thing, again, is this idea of how didactic you wanna be when talking about this stuff. You wanna tell people to trust the science, have faith in science, or you wanna say, "Let me talk you through the process." I'm not holding myself up as some great example of this. I think at times, if you have just a couple of minutes, people, they wanna condensed view of what this means. And sometimes you're forced to consolidate and commit sins of omission, I think, in the process. But I think certainly allowing time to discuss nuanced issues is a lesson. One thing I will say, again, almost philosophically, Dean, is that I did a lot of historical reading during the pandemic, and even going back and looking at The Great Influenza by John Barry. When you read the book and look at that time period, in many ways it had some of the same problems in terms of communication back then. It was obviously a very different time. There was no internet, there was no social media, there's nothing like that, but just the newspapers and subsequently the distrust, the misinformation and disinformation, a lot of that happened back then as well.

0:39:57.5 SG: In fact, if you say it, "What percentage of the population is going to refuse to do X, do a basic public health intervention, take a vaccine, whatever may be?" Usually it's about 17% to 24%, and it was about the same number back in 1918. They didn't have a vaccine, but it was masks at that time and doing other things, so I find that interesting. And I'll take it one step further, if you allow me, which is that that 17% to 24% should not be painted with one brush. I think there are people who within that 17% to 24% are just simply chaos creators, that is their currency. But I think there's other people who are people who just in life have their antennas raised really high. They are the careful ones, they are the suspicious ones. And when you have your antenna raised really high, you often see things that aren't really there, but sometimes you may catch something that everyone else misses as well.

0:40:53.7 SG: And so they don't see themselves as creators of chaos as much as they see themselves as guardians of the galaxy, right? "You missed it, I saw it." And I think you have to separate them from people who are just there to create disharmony and things like that. It's a diverse group of people who fall into that 17% to 24%, and I think you gotta be mindful of that. To just simply refer to them all as anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers, there's obviously an inflaming of the language right away when you do that, and that's not serving a purpose. It's just deepening the divide.

0:41:27.7 DB: Yeah, no, that's right, that's right. And from a public health messaging standpoint, it's so important to actually try to contextualize your messages to audience. And so I think your last point is really important and really a powerful one, we have to protect against these broad-brush characterizations or, otherwise, we will render any attempt at effectively communicating and building trust ineffective. And then the last thing I would note, preparedness becomes so important for fast and early response. As I think back, the vaccine itself was a remarkable scientific success only made possible because of what was in motion before. It's hard to know what will be those key drivers or key factors the next round, but it is that element of preparedness I think that's so critical.

0:42:20.0 SG: It's really interesting, the sort of irony of the fact that the mRNA vaccine was actually something that had been worked on for a long time going back to SARS days, 2003, when they started talking about the idea of an mRNA-based vaccine at that point. And then the projects were fizzled out because SARS, the numbers really died down and they lost the funding and they weren't working on it for coronavirus anymore, but they were still working on mRNA projects, incredible work being done at universities all over the world and Pennsylvania and other places around the world. And then the platforms for this were there. It was this opportunity, I think, in beginning of the pandemic to say, "Could this work? We've been thinking about this for close to two decades now." The irony is that in some ways it was based on all of that work, but the perception was it was brand new, had never been done before, and I think that engendered some of this mistrust as well.

0:43:11.9 SG: I think in some ways it was a rah-rah story, "Can you believe we did it, eight months?" This, that, and everything, but the stories should have always been, "Built on the hard work and backs of men and women for the last two decades." Eight months is part of a much... It's a quarter century, almost 20 years journey this has been. In retrospect, you can say all kinds of things, I guess. But I think that that was an important part of the story, if for no other reason than to pay respect to all the scientists who have been working on this for a very long time. And whenever we told those stories, by the way, people like Barney Graham and others, the audience really responded to that. The story of the vaccine is amazing. The story of the people who helped make it happen are also amazing, and I think that was a great response to that for sure.

0:43:53.1 SG: I do think that, again, it's crazy to me that there was such pride in this. It was like referred to in hush tones by oftentimes very quiet scientists. They would call me up and say, "This is like our own shot." I'd say, "Wow, that's like a really significant analogy." "No, no, this is the moon shot." And here we are, where you have a significant percentage of people who are not taking the vaccine still, so there was all this pride and then you see sort of what it's turned into over three years. And I think, again, that's an important lesson.

0:44:25.8 DB: Absolutely. So, I wanna transition a bit. Last year, you launched a podcast called Chasing Life, which focuses on how we can move forward mentally and physically in a post-pandemic world. And while many activities that were impacted by the pandemic have resumed, there's no going back exactly to the way things were pre-2020. And your podcast focuses on entering a new normal with recovery and reflection in mind. And so I just wanted to raise this topic and spend a few moments just to hear your thoughts on why you started the podcast and perhaps some key lessons that you've learned in the course of hosting the podcast today.

0:45:06.3 SG: Well, we had a podcast that we started almost right at the beginning of the pandemic called Coronavirus: Fact Or Fiction, and it was a daily podcast, and it was an opportunity to do some of the things that you and I are talking about in the sense that you do TV things. And it could be a few minutes, but often times if I wanted to explain these issues more I could just do it in the podcast. And so that was something we did for close to three years, two and a half years. I think at some point, the idea that there was this clear tie-in, first of all, with people's underlying health and their likelihood of becoming as ill from the virus was pretty clear. People who had pre-existing health conditions were more adversely affected, and I think there was a significant desire, as there often is, for people to become as healthy as they can to ward off or decrease their risk of having the more adverse outcomes from the infection. But other than that, I think the idea that we were emerging from this pretty significant event and to allow us to assess each other, to have a conversation nationally about how you're doing physically and mentally and otherwise, to provide some context for life.

0:46:17.3 SG: I remember I did one podcast about the fact that everyone was just kind of more socially awkward than they normally are because we just hadn't been around people for a while. And that may sound like a trivial thing compared to the mRNA vaccines and other things, but the idea that we're gonna start socializing again in a way, and we wouldn't be apprehensive about doing it, there were the issues that I was thinking about. That's kind of why I really decided to start the podcast, and every time I'd have these discussions with people, scientists for the COVID podcast, we would always spend a few minutes before we were talking the science about that stuff, about how you're living your life. Do you find joy? Do you see light on the other side of this? How are you keeping yourself healthy? What are you eating? It was that kind of stuff. And I just was hearing from these remarkable people for all of these different reasons, and this is what we were talking about, so we wanted to turn it into a podcast.

0:47:12.4 SG: And I will say there's one thing about podcasting that is so different than television as well. There's something about just being able to lean into a microphone and just have a conversation with somebody without having to worry about the lights and the cameras and that kind of stuff. I love TV, obviously I'm a television journalist, but podcasting is a very different way of communicating. It's not just one is audio and one is video, it's the style, it's the tone, it's the nuance, all of that, so I like it. I like it a lot. And I also... I'll just tell you this one thing. You'll appreciate this, Dean, I think, is that throughout the pandemic, I've had my wife and three daughters on my podcast. And what that involves is I'm coming down to a tiny little closet in the basement of our house, which is the quietest place we could find 'cause we have to be dogs. And it's tiny, and we sit there right next to each other. No phones can be in there 'cause that'll cause interference on the microphones. And we'll sit there and we'll talk for sometimes a couple of hours, and I talk to my kids and my wife all the time... I do this all the time, obviously. We're a close family, but conversations like that. Try this with your family member some time to just say, "Hey, we're just gonna talk. It's not over dinner, it's not a car ride. There's no purpose here other than to talk." And it's magic.

0:48:28.5 SG: My wife and I have been married a long time. There's things about her that I learned just in that two-hour conversation that she never told me before. That's a little bit of side thing, but it can be really magical.

0:48:39.9 DB: It makes me intrigued about one of your upcoming episode on February 15th on teens specifically, but how screens and social media might affect our brains. And I think it's teens specifically, perhaps I included that because I have a teenager in the house who I'm mindful of, but can you tell us a little bit about that in the time that we have remaining?

0:49:03.7 SG: It's a big topic, and there's so many things that we've talked about even with coverage of the pandemic that I think would be good to remember as we think about covering social media and the brain. They're obviously very different topics, but I think both carry a lot of uncertainty. We're both in a very nascent stages of understanding this. You and I did not grow up with these technologies, we certainly didn't grow up with media. And I think there's a lot of speculation. It's kind of filling the void right now, Dean, as you're asking about covering natural disasters and other things is right now where this is what we're seeing. The basic gist for me is that I, certainly, as a dad of three teenage daughters, want to look at what we do know, what we can say for certain. And also, what does that mean ultimately? The end of the patient visit, what does it mean? What should we do in terms of devices and social media with our own kids? But I think the benefit of the podcast, again, is that we can lean in a little bit more to the nuance. I've interviewed my daughters for this podcast. Again, it's magic to do that for all sorts of reasons.

0:50:02.9 SG: I asked one of my daughters, she's 13. I said, "Do you think that when you're an adult, like in your 30s, will you still use devices and social media and stuff as much, do you think?" And she said, "Yeah, probably, because the United States is a very technological country. It's gonna grow and grow technologically, and that's gonna actually be seen as a sign of success and of progress in other countries around the world." Okay, that's an interesting point. We tend to say, "We gotta like... Dial-up app, we gotta role in the technology," but that's probably not going to happen. But then I asked her, I said, "Is that a good thing or a bad thing?" This is where it could be humbling, being a dad of teenage daughters. She said, "Dad, I don't think you're getting it." [laughter] She said, "It's not a good thing or a bad thing. It's a thing, this is how we are evolving." And I think the idea that sometimes people talk about social, or they talk about devices as an addiction. An addiction at its core treatment would involve abstinence. We cannot be abstinent from these devices. And if you're being honest, as a parent or as a colleague or whatever, you have to recognize that.

0:51:06.7 SG: What I thought was most interesting, and we're gonna talk a lot about this in the podcast, is that we should also be mindful of the fact that this is not necessarily the world in terms of all the devices and the exposure of social media that our kids wanted. This is the world we handed them. If you ask them, you say, "Hey look, think about your grandparents life, think about my life. I have a brother who's 10 years, think about the millennials life." Which do you think was best? Who had the best childhood? And was interesting, all my kids who I interviewed separately for this, said it was probably the generation before ours in between mine and theirs, so more like the millennials. I'm Gen X. And I said, "Why is that?" And they said, "Well, because they had phones, flip phones and things like that, but there was no obligation to be on it all the time." Nowadays, the reason I'm checking my feed is 'cause I feel like I wanna be there for my friends, and it's very affirming teenage girls can be toward each other.

0:52:00.9 SG: Is there the possibility of toxicity? Sure. Is there the possibility of overuse? Sure. But in some ways, thinking of this like an addiction to a drug is probably the wrong framing, more like it's an eating disorder where you need food, but you gotta learn how to pull back the amount that you're eating, not necessarily get rid of it. So there's all these really interesting discussions, I think, that are happening. There's conversations about banning TikTok in the country, you may have heard that. All these sorts of things. I asked my girls a lot about how they use these technologies and what it's doing to their brains, and it's something that I think I learned a lot, and I think the audience will learn a lot as well. And then I take those to the experts. There's a Mediatrician, someone who's a pediatrician just dedicated his life to this, someone who believes that absolutely there should be no social media for children before they get to college and making her case as to why that would be. It's been really interesting, really fascinating.

0:52:53.5 DB: Sounds very fascinating, and I look forward to tuning in. I'm sure many in our audience do as well. We're just about now at the end of time for Ahead of the Curve, so I'd like to sincerely thank Dr. Sanjay Gupta for taking time to be with us today and for sharing some really great insights about leadership in his career. Just a remarkable career still unfolding, and many lessons that I know will be valuable to members of our audience today. Sanjay, thank you so much again for joining us and forever, go Blue.

0:53:25.8 SG: There you go, go blue. [chuckle] It's been an honor. Thanks for having me, Dean.

0:53:32.3 DB: Absolutely, yep. Thanks so much.

[music]

Dr. Sanjay Gupta has become synonymous with health communications over the past two decades in his roles as CNN's Chief Medical Correspondent, podcast host, and author. The two-time University of Michigan graduate ('90, MD '93) continues to work as a practicing neurosurgeon in Atlanta as well. Gupta will join Dean DuBois Bowman for a conversation on leadership, communication, and trust during this edition of the "Ahead of the Curve" speaker series.