Tackling the opioid epidemic: Using alternative therapies and new technologies to curb a national crisis

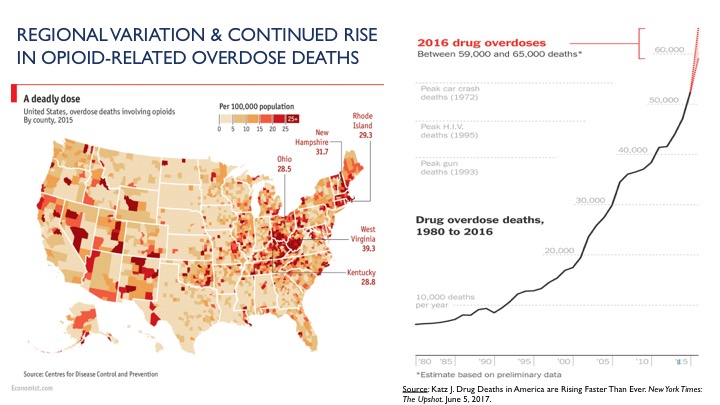

Drug overdose is the leading cause of unintentional injury deaths in the US, and about

90 Americans die each day from opioid overdoses. In 2015, more than 2 million Americans

were addicted to prescription opioids, with about 600,000 more addicted to heroin,

according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Drug overdose is the leading cause of unintentional injury deaths in the US, and about

90 Americans die each day from opioid overdoses. In 2015, more than 2 million Americans

were addicted to prescription opioids, with about 600,000 more addicted to heroin,

according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Researchers at the University of Michigan School of Public Health are working to better understand various aspects of this epidemic. Among them are a chronic disease expert exploring opioid alternatives for people with chronic pain and a health policy researcher looking into how states can best monitor prescribing to curb the crisis on both a population and an individual level.

Making Alternative Treatments More Accessible

One of the biggest challenges physicians face when it comes to managing opioid prescribing is that, while they know opioids can be dangerous, they don’t feel they have alternatives to treating people with chronic pain, says John Piette, professor of Health Behavior and Health Education and Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan.

But alternatives are available. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for example, is a widely accepted, evidence-based approach that can be more effective than opioids in managing chronic pain, explains Piette, who is also director of the university’s Center for Managing Chronic Disease. CBT helps people identify the thoughts and behaviors that may be increasing feelings of pain. Then, this form of psychotherapy helps people develop coping skills that allow them to manage their pain, such as ensuring they are getting adequate sleep and exercise, which are important for pain management. CBT can be used alone or combined with other pain management strategies, such as medication, physical therapy, and weight loss.

Even when doctors are aware of CBT and its benefits, trained CBT providers are few and far between, and most insurance plans fail to provide full coverage for these services. Individual and group therapy are expensive, even with partial insurance coverage, says Piette.

Traditional CBT can also be burdensome for patients. “If someone is experiencing chronic pain, it’s difficult for them to get out of their house and drive to a therapy appointment every week,” Piette says.

Tailoring Therapy

One way to address these barriers to CBT is with mobile health technology. Piette and his colleagues recently completed a large trial built on more than a decade of developing mobile health programs for patients with chronic illnesses in five countries. “Our central question is how do we make this treatment—which we know is safe and effective—affordable and accessible for people in their community, even in their homes?”

In the study, people with chronic pain received automated telephone calls that walked them through a set of recorded messages. Among other questions, the participants were asked how they were feeling, how they were sleeping, and how severe their pain was on that given day. Based on their answers, they received tailored messages to help them work through the issues they were experiencing. The information participants reported went back to a licensed therapist who could review their progress and follow up as needed.

“The patients are supported by a clinical team, without the need for one-on-one consultation,” Piette says. The automated phone call program walked participants through a series of skills over several weeks. It focused on teaching people how to use relaxation to reduce pain, how to pace themselves, how to get on a good sleep schedule, and other skills.

The outcomes were better than those for patients whose pain is treated in a clinic by a trained CBT therapist. Participants said their pain was reduced and they were able to be more physically active.

In related research, Piette is working with the VA Center for Clinical Management Research, the U-M College of Engineering, and the Department of Psychiatry in the U-M Medical School to apply a precision health approach using a specialized form of artificial intelligence. “The program can automatically adapt and give the exact type of message the person struggling with pain needs,” he says. “Based on feedback from that person, it will start to modify its approach.”

“The goal is to make a system that is not one-size-fits-all. It’s really listening to you, just like a good clinician would. We’re giving people as much access to a therapist as they need—but not more—so we can best manage costs and direct scarce clinician resources to the people who need the most intensive treatment.”

While there is cost to implementing this type of program, the goal is to use live services more efficiently, “so the program should be cost-neutral,” Piette says.

Improving Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

While CBT and other alternatives work for some people, there are still many for whom an opioid prescription may be the best course of treatment. Tracking and analyzing opioid prescribing trends can help prescribers and government officials better understand prescriber and patient behaviors and respond accordingly.

One broadly used tracking tool is a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP), a state-level electronic database that monitors controlled substance prescribing. Every state in the US currently has some type of PDMP, though they vary widely from state to state.

“These are very rich databases,” says Rebecca Haffajee, assistant professor of Health Management and Policy at the School of Public Health. “You can log in, look up a patient’s name, and see all their controlled substance dispensing. Especially with opioids, some people are seeing multiple providers and going to multiple pharmacies to get drugs, so these databases can be helpful in combatting that.”

States with the most robust PDMPs generally see a population-level reduction in overall opioid prescribing and use, Haffajee says.

Haffajee has identified several best practices that make certain PDMPs stronger than others. Among them are having timely and complete data, strong incentives for prescribers to participate, user guidelines and education, integration into clinical workflow, and strong confidentiality protections.

Legislation to mandate that prescribers check PDMPs has been approved by the Michigan Senate and is currently under consideration by the state’s House of Representatives. Haffajee, other researchers, and clinicians advised on the legislation.

Looking Forward to Potential Solutions

Looking Forward to Potential Solutions

“Another thing we’re recommending is a mechanism that allows physicians to easily locate treatment providers within the area,” Haffajee says. “That way, if they see a potential high-risk patient, they can get them into treatment, rather than just denying them opioids and sending them home.”

Next, Haffajee intends to look into whether PDMPs are applied differently to different populations. For example, she would like to look into whether prescribers are more likely to deny opioids to younger, healthy looking people than older adults with multiple conditions.

Another concern is the potential for unintended consequences of these policies. If opioid prescribing is reduced, will that push people to the illegal opioid market, causing spikes in heroin and fentanyl use? There is still more research to be done in this area, Haffajee says.

In the meantime, she is cautiously optimistic that strong PDMPs can help the US combat this epidemic. “My sense is that we’ve gotten the country’s attention and the attention of policymakers—the opioid epidemic is now at the top of bipartisan policymaker agendas,” Haffajee says. “And that’s a positive thing. Now, we need to do the best evaluations we can and target the resources the best we can to tackle this head on.”

But that will take time. “It took us two decades to get here,” she says. “And I think it’s going to take us at least a decade to get out, if not more.”