Road Work

For these scientists, highways and byways are keys to health.

From House to House

In the summer of 2014, Kate Helmick, MPH '15, spent a lot of time walking down roads

in rural Thailand. She was part of a U-M SPH team collaborating with Thai scientists

to understand an outbreak of skin lesions in an area of 16 villages. Nearly 30 years

earlier, residents of those villages had learned that they were exposed to arsenic

through contaminated well water. Their homes were situated in the southeast Asian

tin belt, and work in the nearby mines had been unearthing arsenic-containing residue.

The arsenic didn't pose a health threat underground, but once exposed to oxygen it

leached its dangerous inorganic form into the local groundwater.

In the summer of 2014, Kate Helmick, MPH '15, spent a lot of time walking down roads

in rural Thailand. She was part of a U-M SPH team collaborating with Thai scientists

to understand an outbreak of skin lesions in an area of 16 villages. Nearly 30 years

earlier, residents of those villages had learned that they were exposed to arsenic

through contaminated well water. Their homes were situated in the southeast Asian

tin belt, and work in the nearby mines had been unearthing arsenic-containing residue.

The arsenic didn't pose a health threat underground, but once exposed to oxygen it

leached its dangerous inorganic form into the local groundwater.

In the 1990s a Thai university researcher had helped identify homes with contaminated wells, recording her data on a three-by-four-foot map. That research helped connect arsenic exposures to various cancers and skin lesions—evidence that persuaded the Thai government to pipe in safe water to the community. The arsenic was never removed from the groundwater, however, and to this day the well water continues to contain unsafe levels of arsenic. Some people drink the water, and most use it for other purposes, such as bathing.

Today, individuals living in the same village, and even in the same household, may experience different types and severity of skin lesions. No one knows what accounts for the differences, but researchers suspect that epigenetics could play a role. Thai scientists therefore reached out to epigenetics experts at Michigan in 2014 to see if they could help find answers.

"We went house-to-house with this big map. It was a very old-school map," recalls Helmick, who believes it was drawn by hand. Each house with a contaminated well was marked with a red X and assigned a number, which Helmick later used to label the samples taken from residents of the houses.

She collected saliva to analyze an individual's epigenetics and toenails to analyze chronic exposures to arsenic. "It was not the most glamorous assignment," says Helmick.

Although she's no longer involved with the study herself, the research in Thailand is ongoing. Additionally, Helmick's work on the study fostered her interest in water sustainability. "I really saw how not having clean water can impact your life," she says. She is now in her second year of a research fellowship at the Environmental Protection Agency, where she works with the NetZero program, which tests new technology designed to help communities and military bases reach net zero energy waste and water use.

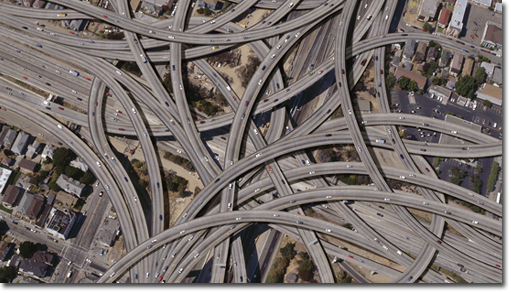

Highway Pollutants

As a graduate student, Sara Adar recruited senior citizens to ride a diesel-powered bus so she could monitor their

bodies for physiological changes. What she discovered was startling: "We could see

changes within five minutes," says Adar, the John Searle Assistant Professor of Epidemiology

at SPH, who researches the impact of road traffic on human health. The seniors' nervous

systems shifted to a stronger sympathetic (sometimes called "fight or flight") response

almost immediately, and they later exhibited greater inflammation in their lungs and

blood.

As a graduate student, Sara Adar recruited senior citizens to ride a diesel-powered bus so she could monitor their

bodies for physiological changes. What she discovered was startling: "We could see

changes within five minutes," says Adar, the John Searle Assistant Professor of Epidemiology

at SPH, who researches the impact of road traffic on human health. The seniors' nervous

systems shifted to a stronger sympathetic (sometimes called "fight or flight") response

almost immediately, and they later exhibited greater inflammation in their lungs and

blood.

In an earlier project, Adar had worked with an EPA scientist to compare indoor pollutants of houses in the suburbs with houses in rural and urban areas. Specifically, they looked at indoor concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a group of chemicals released from the burning of organic substances such as gasoline. "We found that there was a clear pattern," says Adar. Urban houses had the highest levels of pollutants, followed by suburban, and then rural.

More recently, Adar has been working to determine whether traffic jams and congestion are linked to adverse health outcomes. In a forthcoming paper, she and her students show that, for people living next to a highway, there was an increased risk of dying from stroke on days with more nearby traffic congestion as compared to other days.

Air quality standards are important, according to Adar, because they have tangible effects on human health. Research has found, for example, that following initiation of the Clean Air Act in 1970, the drop in air pollution from 1980 to 2000 was associated with a seven-month increase in life expectancy. "It has been said that the Clean Air Act is one of the most cost-effective regulations we have because it saves so many lives, prevents disease, and reduces health care costs. Estimates from the Office of Management and Budget have said the benefits of the Clean Air Act outweigh the costs by 30 to 1 and save up to $400 billion annually," says Adar.

Adar also studies ways to reduce the health impacts of air pollution from vehicle exhaust and other sources. She's currently collaborating on a study in Detroit to measure the effects of placing air purifiers in the home. So far, other studies suggest that air purifiers do reduce concentrations of pollutants in the home, but this reduction has not been conclusively linked to an actual improvement in residents' health.

As an undergraduate, Adar studied environmental engineering. She credits a required toxicology class with stimulating her interest in public health. "The idea that things we couldn't see, that we experienced in our regular lives—in the air, in the water, in our household products—could impact health just really struck a chord with me."

Asphalt Islands

Heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States. Exceptionally

hot days bring increased mortality and hospital admissions. Urban areas are especially

vulnerable to high heat because they contain a relatively large amount of "impervious

surfaces," such as roads, driveways, and parking lots. These surfaces are made with

impenetrable materials that, instead of helping to cool the surrounding area, often

create urban heat islands—regions that are significantly warmer than their surrounding

rural areas.

Heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States. Exceptionally

hot days bring increased mortality and hospital admissions. Urban areas are especially

vulnerable to high heat because they contain a relatively large amount of "impervious

surfaces," such as roads, driveways, and parking lots. These surfaces are made with

impenetrable materials that, instead of helping to cool the surrounding area, often

create urban heat islands—regions that are significantly warmer than their surrounding

rural areas.

As the climate changes, it's important for public health practitioners and city planners to be able to predict which regions are most susceptible to high heat so that they can apply interventions: planting trees in affected areas, for example, or opening cooling centers for residents.

But predicting the temperature in a given spot is not straightforward. You've probably watched your local news and seen the meteorologist report that it's, say, 85 degrees in Detroit. But there is often a significant temperature range above and below what one sees on the Detroit weather map. "It's going to be hotter if you're standing on an asphalt parking lot vs. some place with trees," says Marie O'Neill, associate professor of environmental health sciences and epidemiology at SPH.

O'Neill's former student Jalonne White-Newsome (PhD '11) led a study to see whether satellite imagery might help researchers more accurately predict heat vulnerability. White's team monitored the temperatures at 19 homes across metro Detroit and then compared those temperatures with satellite images displaying impervious surface levels surrounding those homes. Higher ground temperatures were correlated with a higher precentage of impervious surfaces, suggesting that maps including these satellite images could help in identifying at-risk areas for public health interventions.

Despite the relevance of impervious surfaces, O'Neill cautions that other factors also contribute to temperature variability. For example, she and her research team have found that elderly people living in high-rise apartment buildings experienced indoor temperatures in the 90s, even when outside temperatures were in the 80s.

Hidden Costs

How will building a road affect a remote and isolated community over years, and even

decades? That's the question Joseph Eisenberg aims to answer through his research in Ecuador. His goal is to better understand

the dynamics of how roads change communities, so that the costs and benefits of development

can be more equitably distributed.

How will building a road affect a remote and isolated community over years, and even

decades? That's the question Joseph Eisenberg aims to answer through his research in Ecuador. His goal is to better understand

the dynamics of how roads change communities, so that the costs and benefits of development

can be more equitably distributed.

Since 2000, Eisenberg, professor and chair of the SPH Department of Epidemiology, has been conducting research near Ecuador's northern coast. The region's commercial center is located at the confluence of three rivers, in a town called Borb—n. Prior to 1996, Borb—n was populated by a tight-knit community of subsistence farmers. It was geographically isolated and could only be reached through a network of rivers. In 1996, a road was built, connecting town to coast. Soon other roads appeared, opening up the region to the rest of the country.

Eisenberg's research tracks a variety of outcome measures for communities along the road, including diarrheal disease, antibiotic resistance, dengue, and nutrition. He has found, for example, that increased movement of people by road has led to an increased risk of infection and disease, likely due to the introduction of novel strains of pathogens among the previously isolated population. He has also found that, although in theory the region's increased accessibility should provide better access to health care, this hasn't been the case. "They're just now building a hospital in Borb—n," says Eisenberg, noting that residents have had to wait over 20 years.

The road system has made it possible for corporations to extract resources. Deforestation, in particular, has affected the region's water flow and climate, both of which affect local water quality.

In the meantime, the road system has made it possible for corporations to extract resources. Deforestation and gold mining, in particular, have affected the region's water flow and climate, both of which affect local water quality. Social conflicts are increasing, too, as new immigrants move into a region already suffering from poverty and unemployment. Additionally, government subsidies for fuel in Ecuador have made fuel an attractive commodity to smuggle into Columbia. "We've seen movement of petroleum barrels that are going out of the delta and into Columbia," says Eisenberg.

He and his team have also been looking at other measures, like social cohesion and social capital, and their impact on health. They're finding that there's less of both in the road communities vs. the remaining remote communities. This is a potential problem for locals because positive social bonds serve as a protective factor against poor health.

"We're not here to say that roads are bad," says Eisenberg, acknowledging that Borb—n's roads have made transportation cheaper, and individuals have some opportunities for better pay. Instead, he hopes to identify the downsides of development so that such downsides can be proactively addressed in Ecuador and other developing regions. Right now, "a lot of the benefits of the road are being exported."