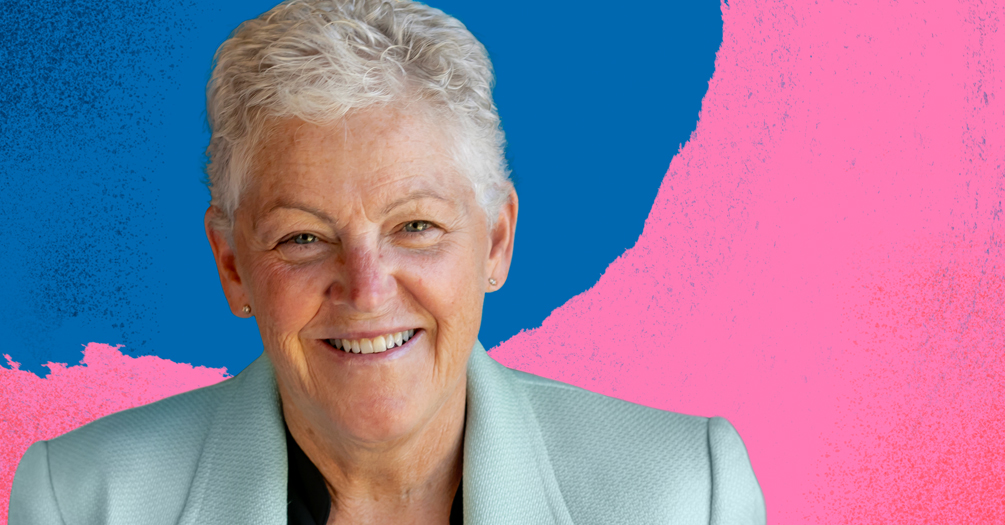

Ahead of the Curve: Gina McCarthy

Listen to "Ahead of the Curve: Gina McCarthy" on Spreaker.

Subscribe and listen to Population Healthy on Spreaker, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you listen to podcasts!

In this special podcast episode, hosted by F. DuBois Bowman, dean of the University of Michigan School of Public Health, we sit down with Gina McCarthy, the inaugural White House Climate Advisor and former EPA Administrator. McCarthy discusses her journey into public health and environmental advocacy, highlighting her experiences working across political divides and emphasizing the importance of environmental justice. As a seasoned leader in climate policy, McCarthy shares her insights on tackling climate change, fostering cross-sector collaboration, and preparing the next generation of public health leaders. Tune in for an inspiring conversation filled with valuable lessons and forward-thinking strategies to drive meaningful change in public health and environmental sustainability.

In this episode

Gina McCarthy

The first-ever White House National Climate Advisor and former US EPA Administrator, Gina McCarthy is one of the nation’s most respected voices on climate change, the environment, and public health. As head of the Climate Policy Office under President Biden, McCarthy’s leadership led to the most aggressive action on climate in US history, creating new jobs and unprecedented clean energy innovation and investments across the country.

Resources

Episode transcript

For accessibility and convenience, we've provided a full transcript of this episode. Whether you prefer reading or need support with audio content, the transcript allows you to easily follow along and revisit key points at your own pace.

[music]

0:00:46.8 Host: Welcome to Population Healthy, a podcast from the University of Michigan

School of Public Health. In today's episode we're featuring a conversation from our

Ahead of the Curve leadership speaker series between Dean DuBois Bowman and Gina McCarthy.

She's the first ever White House Climate advisor, a former environmental protection

Agency administrator and an esteemed professor and environmental thought leader. McCarthy

has had a distinguished career in public health and environmental advocacy, serving

in both state and federal levels under multiple administrations. She's spearheaded

critical climate initiatives and policies fostering bipartisan support and driving

forward the most aggressive climate actions in US history. Join us as we delve into

McCarthy's journey into public health, her experiences working across political divides,

the importance of environmental justice and her insightful perspectives on the future

of climate action. McCarthy also shares invaluable advice for the next generation

of public health leaders. And now here's Dean DuBois Bowman.

[music]

0:02:00.8 DuBois Bowman: Thank you for joining us for Ahead of the Curve, a speaker

series from the University of Michigan School of Public Health, my name is DuBois

Bowman, and I serve as Dean of the School of Public Health. Ahead of the Curve speaker

series focuses on conversations about leadership, and throughout this series we have

discussions with contemporary leaders to hear about their insights, their vision,

and their stories of perseverance. Leadership is a critical component of navigating

complex health challenges and building a better future through improved health and

equity. We want to hear about the important factors that shape great leaders and we

want to learn how they continue to evolve and grow so that in turn, we can help to

train the next generation of leaders. We have a fantastic guest with us today to explore

these issues. I'm delighted to welcome Gina McCarthy, the first ever White House Climate

advisor, former EPA administrator, professor, and environmental and public health

thought leader.

0:03:00.4 DB: Gina has had a long career in public health and environmental advocacy,

having worked at state and federal government levels for many years. From 2013 to

2017, Gina was the administrator of the United States environmental Protection Agency

under President Barack Obama, and then after leaving the EPA, Gina served as a professor

of practice in the Department of Environmental Health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School

of Public Health, as well as President and CEO of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

From 2021 to 2022, she served as the first ever White House climate advisor under

President Biden, and in this role her leadership led to the most aggressive action

on climate in US history, creating new jobs and unprecedented clean energy innovation

and investments across the country. Since leaving the Biden administration, Gina is

completing a climate fellowship for her Alma Mater Tufts University. She's also an

advisor for private equity firms on climate- and sustainability-focused investments,

and she's co-chairing a group coordinating climate policies between the United States

and India. She most recently joined the climate Initiative America is All in as managing

co-chair. Gina, thank you so much for joining us today, I'm really delighted to get

into the conversation.

0:04:27.1 Gina McCarthy: Hey, thank you. It's great to be here, and I apologize for

the long introduction but I'm old, I mean this is what you get.

[laughter]

0:04:36.1 DB: I want to start really toward the beginning and talking about how you

first got interested in public health and environmental work. And as you reflect back,

can you think of early life experiences or even educational or career experiences

that prompted your interests in the field?

0:04:57.0 GM: Probably a lot, sure. Let me just start by saying that, I have always

had difficulty because I never knew what I wanted to be when I grew up. [laughter]

And that started from day one, I just wanted to learn stuff. I just wanted to be active

and engaged, on issues that I cared about. And honestly, when I was a kid I grew up

in the '50s, '60s, '70s and we're talking about a public health challenge, when you

saw the air pollution challenges spewing smoke out of old coal units. And we had a

textile factory near us where the river would run red or green every day, depending

upon what crappy dyes they were putting into their products. So I'm used to fighting

and being engaged on issues both locally, but then at the state and federal level.

0:05:57.7 GM: And it just came naturally to me to recognize that all of these pollution

challenges, and more recently of course, over the past 20 years, focused on the climate

challenges, you realize how interrelated health is on these issues. And so I've had

a great opportunity to work at the local level, I really got my feet wet there, my

undergraduate degree was in anthropology, that may seem like it's disconnected from

public health but it isn't, it gives you great sense of human nature, how people actually

work as communities, how do you really find a way to intervene in a way that's going

to be helpful and provide more safety and security. And I went to work in a really

small town as my first real job and I was the public health agent for the town.

0:06:57.9 GM: Now of course I took that job knowing nothing. I had no idea what they

wanted me to do, and it turned out I needed to learn about septic systems, sewer systems,

wells, and public drinking water, you name it, you get thrown at you for dumping in

the woods pollution, we had all kinds of challenges. And it was a great experience

for me, but the connecting thing was health, the connecting thing was public health,

and it kept me going because you get to have fun with people and serve them at the

same time, to me public service is it, that's all I ever wanted to do. And I like

making money now, that's not bad, but it's not as much fun.

0:07:48.1 DB: So, if we can kind of drill down on that, I appreciate hearing just

some of what you were observing in your own environment and thinking about exposures

and the impact on health. But if we talk specifically about the topic of climate change,

you've described climate change as an intersectional issue for example framing it

as a human rights issue, a youth issue, a racial justice issue and then, importantly

one of the key intersections that you include regards climate change as a health issue,

so if we're talking about climate change specifically, why is it important to regard

climate health in part as a health issue?

0:08:28.9 GM: I don't want to give too complicated or long an answer, but it seems

self-evident to me that health is so critically important, and that when we all became

aware of the challenge of climate change, it became very apparent to me that it was

a driving factor in health. When I first went to the federal government, I had been

working in the state of Massachusetts for a while then I ran the agency in Connecticut,

the environmental agency. And then I got a call asking if I wanted to join the Obama

administration, and I told them of course, but only if you give me the air program.

[laughter] And they said, okay. And they kept trying to take it away from me because

everybody wanted it, and I said, "Nope, I'm going to keep my butt in Connecticut,

or I get the air program."

0:09:25.2 GM: Because air quality is such a fundamental challenge from a health perspective

and so much contributes to air pollution, including the challenge of climate change,

it's intersectional with everything that we get to do and think about, and it remains

a passion for me. I've helped to set up a new international group that's looking at

clean air, I'm working with Bloomberg on Breathe Cities because it's so fundamental,

and we forget how many billions of people every year are dying as a result of exposure

to dirty air, we just have to get at it. And one of the reasons why I took that job,

I will be very honest with you, that at the time that President Biden won the election,

I was very happily getting paid money at Natural Resources Defense Council to run

that nonprofit, and it's a superb organization in New York.

0:10:24.9 GM: Only that's when Covid hit, and I ended up getting a call from President

Biden. And the reason he asked me to become White House advisor was because we knew

each other when he was vice president, the reason why I took that position was number

one, he described his position and this position that he wanted me to take in this

way. He said that this is about Covid hitting and people having no sense of hope or

opportunity, we need to deal with climate change because it's a contributing factor

in so many of the challenges that he knew were already here and happening. And he

basically said, "We're not going to talk about climate change as a sacrifice, we're

going to talk about it as an opportunity, we're going to talk about it as an opportunity

to lower our energy costs, as an opportunity to lower air pollution, as an opportunity

to protect our water quality." And he just kept going on and on, and I'm like, I jumped

at it because he realized that climate and health are absolutely intertwined as health

is in many things. But to me it's always been about air and water pollution, and it's

always been about climate, that's what I do.

0:11:51.3 DB: Thinking about those issues, and then as I think about the field of

public health, something that's so central is the understanding that different communities

can have very different health trajectories based on specific circumstances and experiences

impacting those living in the community, so as you mentioned air and water as examples.

And this notion is certainly true as it comes to a topic like climate change specifically

as well, and so I was just wondering if there were experiences professionally for

you or otherwise that opened your eyes to disproportionate impacts and the need to

address these issues through a lens of environmental justice.

0:12:31.0 GM: There are so many, and honestly, I think that I stuck my nose to the

grindstone pretty well when I was working in the states and pretty well when I went

to EPA. And it was when I was EPA administrator that I had the flexibility to really

expand my focus and my travel so I could literally see what was going on across the

country, because you can't be a public servant and stay in your office, it just doesn't

work that way. And so the trips that I went on, I think the two that had the most

impact to me was one of the times when I went to Texas and I was down in the Gulf

region, and I could not believe that human beings could live that close to oil and

gas industries. I mean massive tanks, massive tanks, people's homes would be within

20 feet of the big chain link fences as if that's a protection, it's protection for

the companies, it does nothing for the communities that live there.

0:13:48.0 GM: And I did public meetings there, and really some of them were heartbreaking,

just absolutely heartbreaking about the health challenges that they were experiencing

and how incredibly difficult it was to actually get at these root causes of problems

and get the regulatory system to be able to really do its job, it's rulemaking job,

that was hugely eye-opening for me because we had been pushing for so long that I

thought we had made more progress than this. And I'm looking at it going, "How do

we let these pockets of poverty?" Because we know that these health impacts are relationally

aligned with the income distribution, the poverty challenges that we're seeing, the

social challenges, racial challenges, these are all bunched together and have to be

fought and understood as one. And the other one was going to Louisiana, man if you've

ever not been to Louisiana, you have to go there because the whole corridor of industries,

mostly plastics industries, all fossil fuel based is still there, they're still humming,

and I'm still seething about the inability to be able to tackle these problems effectively.

So, as you can tell I might have left the job, but I take the job with me and while

I'm focused more on climate, I refuse always to disconnect that from public health,

it's just inseparable.

0:15:25.1 DB: I want to actually shift gears a little bit. During your career, you've

worked for both Republican and Democratic administrations, and it's no secret that

American politics especially as of late has been very divided, and it can be hard

to reach across the aisle to get things done. And as we focus on training future public

health leaders, it's so important for us to be able to train our students to work

effectively across lines of difference. And if you can just maybe reflect and comment

on how you've been able to work across differences in partisan political environments.

0:16:03.0 GM: Yeah, I've worked for six governors, five of them were Republicans and

I'm a staunch Democrat. But that didn't mean I couldn't effectively get stuff done

[laughter] because you have to follow the science and be clear. I think communication

is everything, you have to see what you can do and what's the best you can do and

keep moving it forward knowing that if you don't do it, it won't get done. I worked

in Massachusetts and in Connecticut and frankly, it's a lot different in other states

clearly. But I think we were able to make real progress, and I did it because I reached

out to constituency groups. We had people in all the NGOs working for us, or with

us I should say, to get people involved and engaged because at the state level that's

essential because that's how change happens.

0:17:08.7 GM: And so we worked with them and I worked across the aisle every chance

I got. I didn't win every time but when I won, I won big, because you have to keep

moving forward. But at the federal level, it's even more difficult. I worked for two

presidents: Biden, and prior to that President Obama, they were both Democrats, but

that didn't really help with the difficulty we had in Congress between Republicans

and Democrats, but it was frankly a lot better than it is today. But I did everything

humanly possible to establish a personal relationship with the Republican colleagues

even when they didn't agree with me. I would literally have them come up before a

meeting and say, "I'm really going to pound you." I'd go, "Go for it, I'm ready."

You know what I mean, I'm not suggesting it was a game, but I am suggesting that neither

of us left there without a shaking of your hand, a recognition that we were both doing

our jobs. And I did my best, and I think in many cases, soften the blow for some of

the rules that went through because you spent time with people and you have to, it's

a personal as well as a business relationship that you need to have, and that's how

human beings can get to get over obstacles that otherwise would've prevented them

from working together.

0:18:39.3 DB: Absolutely. And as you're responding, just kind of thinking about the

complexity of the problems that you're working on that are not Democratic problems,

they're not Republican problems, they are problems that we have to solve together

and your response really shares the foundations of what it takes effectively to be

able to work across political lines of difference.

0:19:03.1 GM: I mean, none of us are wearing a big scarlet letter that's an R or D.

If you go into it with that attitude, it's first of all disrespectful, but it's also

counterproductive. [laughter] If you want to win, there were many times when I think

some of the Republicans felt they had to vote against something, but they had talked

to me afterwards and I'd recognized that they kind of liked it, and it was the same

with our industry players, you had to be reasonable, you had to figure out what they

could actually do without putting them out of business, you had to get that sweet

spot for how can you calculate the health benefits and maximize them, but at the same

time actually get this done, and you had to work with outside groups.

0:19:53.8 GM: I had a lot of outside groups that really helped us to get over the

finish line by doing their own lobbying, but also just by going out. We started a

whole moms group called Moms Clean Air Force, and that's all they did was go around

the country and talk to people about why we needed cleaner air and how to get there.

And all those things were precious opportunities for me to realize that we cannot

be without hope, because individuals out there, families need it and they're willing

to jump in. Public service has been just an amazing gift for me.

0:20:34.0 DB: The work that you do has the good fortune of sitting on an evidence

base. One of the challenges now is that there's so many sources of information, including

sources of misinformation and disinformation, and this affects many topics in public

health. And as I think about an issue like climate change, certainly present there.

And so just wonder if you can kind of comment on that factor in the work that you

do of how you've effectively worked with people or help to support and serve people

who may not acknowledge, believe, or even recognize the impacts of climate change.

0:21:11.8 GM: I've tried to figure out how to distinguish the difference between science

and belief systems. [laughter] It's a bit frustrating when people come in already

having chosen their position on the basis of listening to the information that's incorrect.

It's hard but again, it's about recognizing that people are not perfect, people are

people, and we make science very complex often for people. Now when we do rulemaking,

it was essential to go into the complexities and make the arguments you needed to

make and defend what you were trying to do, but in human terms, we talk in language

that people don't understand, many people. And we also, they rely on information that's

not right, we're seeing that right now as the misinformation is just incredible. I

think that's going to continue and in fact get a lot more difficult as AI continues

to sort of expand in a way they're expanding right now, and in a way that's unregulated.

0:22:27.5 GM: There's nobody who's the referee here that can cry foul, you can say

anything you want. I think the important thing from a public health perspective is

that you have to do your job on the basis of science, but you also have to translate

that science in human terms. The reason why I think I've been successful in getting

some difficult things done is I always focused on what it meant for human beings,

and our natural resources that we relied on. You have to put it in clear terms, you

won't win everybody, there are people that will still disagree or think you've done

the work wrong or intentionally wrong at times, but you have to do it, nothing is

easy that's really, really good to do. [laughter]

0:23:21.2 DB: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think that's great insight for our listeners, I

think specifically even about our listeners who are still on their education journey,

our students. I think there are a lot of lessons to be drawn for us as a scientific

community on how we translate perhaps methods of dissemination in the past will no

longer be as effective as they once were and it's our responsibility to figure out

the adjustments to make to affect those communities that we intend to support.

0:23:54.4 GM: I think the challenge on climate is probably the most extreme challenge

that you're going to have in terms of a communication strategy. And honestly, if we

just end at talking about greenhouse gas emissions, we are definitely going to lose.

[laughter] We have to talk about public health, we have to talk about air pollution,

we have to talk about whether we're going to have enough water to drink and will it

be clean. All of these things have to be put in human terms because some people see

it as being fake, other people see it as being too expensive for them, it's going

to get really hard. And I think with the technologies and practices and programs we

have now, it's very clear that none of that is true, the shift to clean energy is

the most cost-effective shift that we can make for our economy and for our families

and for their pocketbooks, I think communication is just essential. And I talk to

scientists all the time about that, they spend a great deal of time talking in language

that people really do not understand, but they're trying hard now to figure out how

to learn those lessons and to make it in language that people will begin to relate

to and then can make their own judgment.

0:25:20.7 DB: I want to talk a bit now about how different sectors can work together

to advance some of these issues pertaining to the environment and climate. And when

it comes to climate change and environmental justice public health as we alluded to

earlier, sometimes is a part of the conversation, sometimes less so. And talking across

sectors I want to start with academic public health, what can academic public health

contribute to advancing solutions in this area? And how can public health scholars

best work with policy makers on climate and health issues?

0:25:57.5 GM: I could be wrong, but I think this is happening a lot, I think there's

a lot of communication going on between the public health community and the advocacy

community, and as you described them scholars. But I think they're not interchangeable,

it's about partnership, it's about collaboration, who has the skills to do what, how

do you work together to make change happen and to make people understand the benefits

of that change. I think that a lot of, I know that a lot of the ways in which people

started to talk about climate change was to make it as scary as it possibly could

be, that was not a wise choice. But at that point in time, there weren't many solutions

to it. But when there is, it just opens up a world of opportunity to actually get

people excited and engaged rather than fearful.

0:27:00.0 GM: And I think that goes for anybody that's working in the public health

field, is they have to work in areas where they can translate the challenge into that

opportunity framing and make it clear, instead of trying to sort of continually look

closer and closer at the number of deaths, nobody relates to that, it's sad, but it's

true. But they care about what their family's doing and their communities, and I'm

not saying that because I feel people are weak are wanting, I think it's just human

nature. That's all that we tend to fight about, is how do you communicate with people

to engage them in a positive way. And that's true of every aspect of health, every

aspect, it's the frustration of my life that we haven't been better at getting an

air quality. I can't understand it.

0:28:03.5 GM: We're finally getting air monitors in Africa, can you believe it? Seriously?

This is what we're doing right now, I just can't get over it. And when you do that,

if you start measuring things and making that measurement visible, people sit up and

go, "Huh, compared to what?" And so we have to be bold about getting information out

in a public way, but we have to make sure to translate that into something they can

grab a hold of.

0:28:39.5 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. And if I think about government as a sector,

either at a state level or a federal level, how have you seen environmental agencies

and public health agencies work together on climate and environmental issues?

0:28:57.1 GM: That's a really good question because at times the relationship has

not been very tight. But I think that's not true now, at least the states that I've

been engaging with and many I know, are really looking at the opportunity to look

more holistically at these challenges and in a collaborative way. And so I'm kind

of excited about the partnerships that are increasing in terms of wanting to make

sure that we take a multi-discipline approach to these issues. I just think it's essential.

0:29:30.6 DB: Lastly, I'll point to the private sector. Clearly a huge contributor

on the one hand to issues around climate change, but also solutions around climate

change, and so we need to work with them to be able to pursue and advance some of

these solutions. And so, what are some of the most effective ways that you found to

engage with the private sector in this work?

0:29:51.4 GM: Yeah, I mean the federal government is important, but to me change in

all cases starts at the bottom up. [laughter] I loved working in local communities,

loved it. And then you go to the state level and that's fabulous too, then you can

go to the federal level if you want. But every part of that means that you have to

have a skillset that is broader than your expertise, and that is your ability to work

together to develop a multi strategy, that you can get your arms around and work forward

on. Right now, I know that there's lots of concern that we're not gonna have any federal

work on climate, which is probably true for a while, but what I know is that because

cities and states have to pay attention to their population that they start activating.

0:30:54.5 GM: And I saw at the last Trump administration, we hardly lost anything,

we so quickly built it back when the next administration came in. And so the role

of the public sector, it's actually pretty exciting today because clean energy is

not just happening in the United States and in fact, they're doing very aggressive

strategies in the EU, there's a lot of work going on internationally on these issues,

and for the public sector, it's all about investments. Now that's an okay thing because

they're the private sector, that's what they live on. But they have found opportunities

to really invest in a way that is at its core, a public health investment and a climate

investment, that's the work that I have been following and doing and helping with

because there's so much to be done that really benefit the entire world.

0:31:53.4 GM: I've been working with the World Bank, they asked me to do some work

on a report that's going to be coming out, I think within the next couple of months,

they're very slow by the way. Within the next couple of months on climate and public

health and it's basically air pollution. And it's going to be really eye-opening.

It's been a great experience for me to see how they get data from a variety of countries

and how they extrapolate that into some meaningful statements and opportunities to

move forward. And then the private sector, the two things I had with the private sector

is one, they have to make money—I get it, that's what they live for. When I did rulemaking,

I sat down with everyone who ran the largest utilities, I went to them if they didn't

come to me. I talked to them all the time when they had a good thing to say about

something, maybe we were going too far, blah, blah, blah, I'd take a look at it, we'd

make changes.

0:32:55.6 GM: Now, it's not that you negotiated something <inaudible>, we negotiated

something they could live with, that's what you tried to do. And I think in terms

of investment, it's the same thing, how do you make investment opportunities in the

global south, that can actually provide meaningful, sustainable development? And that's

some of the work that I'm doing now, which relates to regenerative farming and women

farmers and other efforts underway now that should provide at least some opportunity

for change to begin to happen in investments to begin to flow.

0:33:37.6 DB: I hope your work that you're describing in your career to date and as

it continues, really serves as a model for some of our students who will soon be at

a point where they're making choices about which direction to go in in their careers.

But your work really reflects the necessity and the opportunities to work across some

of those sectors and really, to do so in ways where you also understand the perspectives

of partners in order to be able to work effectively.

0:34:01.0 GM: Yeah, it's essential. I started out by saying I never really knew what

I wanted to do, and I did that on purpose, I do it a lot. Because I feel like students

often pick a career path before they have really figured out that it was what they

would fall in love with. [laughter] And I think people need to take a deep breath,

they need to look at a variety of different opportunities that they might have to

really dig deep into health issues and consequences and solutions and opportunities.

I tried things that I didn't know if I could do, because I just didn't know, I don't

know if I can do that, you have to stretch. The minute you're comfortable to me, you

might as well go do something else, you know what I mean? You've got to grab for the

challenges.

0:34:58.4 GM: And I can't tell you how many times I went through discussions about

jobs with people when I knew absolutely nothing about what I was talking about. In

my younger years, as soon as I got my first job in Canton, I had to go buy books on

what the hell do they do? What does a job like this do? I had to go out and get some

certificates to be able to do, it's been a blast. So, I just don't want people to

program their lives, I want students to know that they have large opportunities to

continue to grow in many different ways. Probably you should tell the truth at job

interviews, that's always a good thing. I didn't lie, I just didn't completely tell

the truth.

[laughter]

0:35:50.1 DB: So, we're at January 16th, a few days away from the presidential inauguration,

and there's been a lot of talk about how the incoming administration will handle climate

issues and how it might shape environmental policy at the federal level. And from

your experience, if you can just kind of talk to our audience about what ways each

new administration gets to actually shape what happens let's say, at the EPA and then

what it takes to get things done.

0:36:18.6 GM: The federal government is, as everybody knows, pretty big, and even

at EPA when I was there, it was like 15,000, it's quite a bit more than that because

of money that they've received to expand their opportunities there. The federal government

is filled with incredibly honorable, smart, and clever people. As we saw during the

prior Trump administration, they rolled back some rulemakings that they didn't like

and they figured out how to do that, but very little beyond that. It is very hard

at the federal level for you to change a final rulemaking as long as within the period

of time when Congress can't arbitrarily change that, which is a pretty small window.

So I think Congress is looking at opportunities to roll back things, but I think they're

going to find it hard. But the best thing about the federal government employees is

that they're not just smart, but they're very loyal to their jobs.

0:37:17.7 GM: They went there to do their jobs, not to mess it up, and we didn't lose

too many people last time because they didn't want to leave. And while they may have

had challenges with changes in their job or other things, but it was undone as quickly

as the next change in administration. But having said that, it's so hard to predict

what this administration is going to do. I think you and I know that they're bringing

in outside people to come in to dismantle the federal government, which they call

nasty names of, I'm hoping that it's a lot of talk and that the folks in the federal

government continue to what I call, keep their butts in their seats.

0:38:04.3 DB: Yeah, and for those who may be feeling angst about the direction of

environmental policy over the next four years and beyond, what are some of the ways

that members of the audience can channel their energy over this time period. People

who are feeling the urge to act, and the urge to act now?

0:38:18.0 GM: I think your best bet is to see if you can do some work in your local

communities, some work in your cities, some work in the states. There's always a need

for people willing to jump in who have a science background or a health background

because health impacts everything, and science is the core in which everybody at least

should make decisions. And so, I would encourage people not to discredit how exciting

it actually is to work at the community level, and at the city and state level. We

are going to have governors like crazy fighting to make sure that we maintain the

Inflation Reduction Act, which has given them so many billions of dollars across the

country, and I think they're going to want to hear from people and they're going to

want support on how to translate, what they're doing into language that everybody

will get excited about and want to expand.

0:39:20.9 GM: It will be difficult at the federal level, but I don't see the same

challenges at the state level. My mother had this old saying: don't cut off your nose

to spite your face. That's what I'm telling the Republicans in the districts in which

they've received millions of dollars and lots and lots of projects are going. I think

it's a very good thing to remind them that these are their constituents, this is who

they work for. So, I'm pretty comfortable that those issues will arise. There's so

much you can do with a public health degree, you know that. Public health means one

thing to one person and another to another, but it's always fundamental to decision

making always.

0:40:07.1 DB: Absolutely. So, I want to talk about some of your current activity.

So recently you've taken on a position as managing co-chair of the America Is All

In coalition, and this is the most expansive coalition of leaders ever assembled to

support climate action in the United States. They come from thousands of cities and

states, tribal nations, businesses, schools, etcetera. Can you tell us more about

the goals of the coalition and why you decided to join?

0:40:38.6 GM: I decided to join America Is All In mainly because when I was at one

of the <inaudible> in Egypt a few years ago, that was when the Trump administration

wasn't doing much. He had dropped out of the Paris agreement and Mike Bloomberg gratefully

said, I'll put up lots of money, let's go give the US presence internationally, and

he did that, and I helped with that. And so I started then an ongoing relationship

with America Is All In In that I reengaged in after the White House. And really it's

all about working at the local state levels to get people engaged and excited about

acting on climate. We bring together a lot of players, we go across the country, we

help with things like giving cities access to how you get the inflation reduction

act money, we'd give sort of remarks, we go to colleges, we go to universities, we

just get out on the road and explain the opportunities that we all have available

today to actually make a change tomorrow. [laughter]

0:41:53.1 GM: And so it's really fun and interesting. And part of it is working with

folks like Governor Inslee in Washington and I worked with Lisa Jackson, who's at

Google. Governor Pritzker soon will be joining, and the governor in California. It's

so much fun actually to talk to them and see how engaged they are, but it's even more

fun to talk to mayors for me. [laughter] There are literally hundreds of mayors that

have joined this coalition. They're trying to learn what they can do with their communities

to protect people, to actually build in a way that is sustainable, to look at what

does adaptation really mean? How do I build for the future and how do I engage people

in my community to act and to get out there. I love that work, it is the best because

mayors collaborate with one another, they share information on how they got things

done. What were the problems?

0:43:01.2 GM: How does the rest of us avoid those challenges? So, just bringing people

together is amazing. We've got Mayor Bibb who is really an outstanding young man,

and he is so articulate and passionate about what he's going to do with his city,

and we've got tribal leaders and tribal nations that see firsthand the devastation

of climate and frankly, it probably hurts their heart more than it does mine, it's

such a preventable problem and it's so devastating for them. And we work with them

to try to figure out how do we keep ourselves going? How do we work together? How

do we learn from one another? How do we share our experiences and our expertise? And

we'll do that again and frankly, as I said before, that's where change happens. And

all-of-a-sudden everybody wants to do the same thing, and it's great. I wish that

I thought the next administration wasn't doing what they say they're doing, we've

got to be prepared for it and we've still got to move, and that's what it's all about.

0:44:07.7 DB: Absolutely. So, I want to ask a question that, may be no surprise given

that it's one that rings close to home and I want to thank members of the audience

who submitted questions at the time of registration. And some variation of this question

is one that I got a lot during registration, and that is really focusing on the Great

Lakes. Of course, here in Michigan, we're surrounded by the Great Lakes, which contain

one fifth of the world's fresh surface water supply, and I just want to probe your

thinking about things that we can do here in Michigan to protect this vital resource.

0:44:43.3 GM: That's a really good question, I've worked with a couple of people who

are commissioners that oversee a lot of the work on the lake in terms of maintaining

its vibrancy, but doing that in a way that looks to be protective of the natural resources

that border the lake, and I think it remains a significant challenge. There remain

challenges with how to handle sewage effluent, there's challenges with how to keep

the canals free of pollution, it's always going to be a challenge, but it is an incredibly

beautiful place.

0:45:22.7 DB: Absolutely. So, we have time for one last question, and I want to really

return to thinking about our students. What advice would you give to our students

who are taking their first steps in their careers as future public health leaders?

0:45:37.2 GM: I guess I would ask them to be open to not define their path as clearly

as some of them might think they have to. For me, it was all about knowing that it

was an issue that would always be one that followed me no matter what I did. Public

health to me is it, that was always the thing that I cared about and thought about

the most. When I went to Tufts, I went to the environmental health engineering program

because I was driving them crazy about why more wasn't happening to protect public

health. So, you can go at it at very different angles, but don't chart your path so

clearly and decisively that you miss opportunities that are right in front of your

nose. Because I think it allows more vibrancy and excitement in your life.

0:46:31.5 GM: I never wanted to be in the same job for a whole long time because I

felt like it would stifle me to some extent. And don't be afraid that whatever your

degree is, that it doesn't exactly fit a job that might be open, it's all about what

you do when you get there and start talking to people about it and how excited you

can be about bringing in some new ideas and new perspectives. That's how things should

work. And so, for me it did, and I would encourage students to equally be bold, go

out there, get lots of different ideas of what you can do for a living.

0:47:11.2 DB: Absolutely, absolutely. So we're just about out of time now for Ahead

of the Curve, and I'd like to thank you Gina, for taking time to be here with us today

and for sharing some really great insights about your leadership and your career,

there are so many lessons embedded for all of us but again, thinking about our students,

just you as a model of how you've continued to grow, how you stretch at times and

have benefited from that throughout your career. Such a fantastic conversation, we're

thankful to have you here. Thanks to all of you for joining us here in Ann Arbor on

a snowy winter day. Be well, stay safe and forever: go blue.

[music]

0:47:56.9 Host: Thanks for listening to this episode of Population Healthy from the

University of Michigan School of Public Health. We're glad you decided to join us

and hope you learn something, that will help you improve your own health or make the

world a healthier place. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe or follow this

podcast on iTunes, apple podcast, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you

listen to podcasts. Be sure to follow us at, UMICHSPH on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook

so you can share your perspectives on the issues we discuss, learn more from Michigan

public health experts and share episodes of the podcast with your friends on social

media. You're invited to subscribe to our weekly newsletter, to get the latest research,

news and analysis from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Visit public

publichealth.umich.edu/news/newsletter to sign up. You can also check out the show

notes on our website, Population-healthy.com for more resources on the topics discussed

in this episode. We hope you can join us for our next edition, where we'll dig in

further to public health topics that affect all of us at a population level.

Related Content

Explore the topics discussed in this episode further with our curated list of resources. We've compiled relevant materials mentioned in this episode so you can dive deeper into the conversation.