Health equity, leadership, and action: Insights from Dr. Rachel Levine

Listen to "Equity, Leadership, and Action: Insights from Dr. Rachel Levine" on Spreaker.

Subscribe and listen to Population Healthy on Spreaker, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you listen to podcasts!

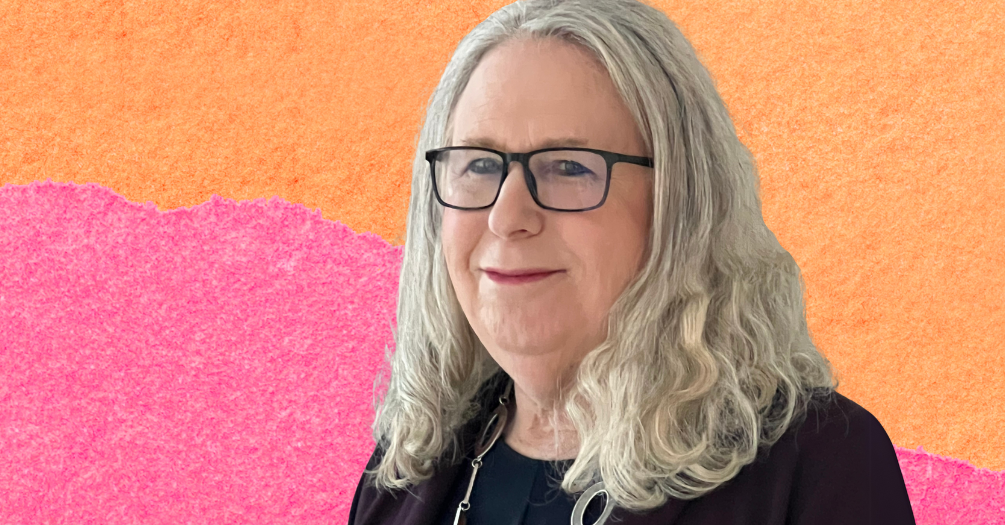

In this episode of Population Healthy, we bring you an engaging conversation with Admiral Rachel Levine, MD, USPHS (Ret.), former Assistant Secretary for Health at the US Department of Health and Human Services. Recorded at a recent live event as part of The Exchange: Critical Conversations with Michigan Public Health, Dr. Levine joins Dean F. DuBois Bowman in a conversation about gender and health equity and shares her experience and vision for achieving health equity. She offers an inspiring call to action for public health professionals and advocates, emphasizes the importance of stepping out of comfort zones, and highlights the need for collaboration across political and social divides. The discussion also touches on her leadership journey, strategies for navigating partisanship in public health, and the challenges and opportunities in providing healthcare for transgender individuals. Listen in for a thought-provoking exploration of contemporary health issues and the pathways to health equity.

In this episode

Admiral Rachel Levine, MD, USPHS (Ret.)

Former Assistant Secretary for Health for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

Levine is an American pediatrician who served as the United States assistant secretary for health, the admiral in charge of the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, from 2021 until 2025.

She is a professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at the Penn State College of Medicine, and previously served as the Pennsylvania physician general from 2015 to 2017 and as secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Health from 2017 to 2021. Levine is one of only a few openly transgender government officials in the United States, and is the first to hold an office that requires Senate confirmation. On October 19, 2021, Levine became the first openly transgender four-star officer in the nation's eight uniformed services.

Levine was named as one of USA Today's women of the year in 2022, which recognizes women who have made a significant impact on society.

Resources

Episode transcript

For accessibility and convenience, we've provided a full transcript of this episode. Whether you prefer reading or need support with audio content, the transcript allows you to easily follow along and revisit key points at your own pace.

[music]

0:00:42 Host: Today's episode of Population Healthy, a podcast from the University of Michigan School of Public Health, comes from a captivating discussion during a recent live school event. Today we bring you insights from Dr. Rachel Levine, the former Assistant Secretary for health at the U.S Department of Health and Human Services. She joined Dean DuBois Bowman in conversation at a recent seminar called Health and Gender Equity in the Modern Era. Join us as we explore Dr. Levine's compelling vision for a future where health equity is a reality for all. And hear her inspiring call to action for public health professionals and advocates. We join the conversation now.

0:01:17 F. DuBois Bowman: I wanna start still with our students in mind. And one of the key benefits of having a program like this and other programs that we do is, our students get exposure to tremendous leaders like yourself. And to be able to have a lens and insight into impactful and influential work at the highest level. And so to start there, can you share more about what it means to be Assistant Secretary for Health and what were some of the things that you focused on in your job?

0:01:43 Rachel Levine: Sure. Thank you. Well, it meant the world to me to have this position. It really was an amazing, unique opportunity to help people. Really in my medical career and in my public health career, I have felt very gratified by that, because all I tried to do and all you're all trying to do, now and in the future is to help people. You do that in medicine, you might do it patient by patient, developing programs or teaching, but in public health, you are able to do this with this broad brush. First for me in Pennsylvania, and then nationally. And so, it was a unique opportunity to do that. We focused on health equity. Health equity is foundational to all of our work. And that started with our secretary. Secretary Xavier Becerra, and he gave us those marching orders for every different division at HHS. And so, our work, I really divide the work that I had as Assistant Secretary into three different categories. One was the Public Health Service Commission Corps, leading those fantastic officers who do medical and public health work throughout our nation. The other was leading the offices. And so we focused on reproductive health care and Title X programs and the syphilis crisis.

0:02:58 RL: We focused on food and nutrition security and food is medicine. We focused on Long COVID and formed an office of Long COVID Research and Practice. I focused on LGBTQI+ health equity. We focused on the environmental work and the climate change work, ending the HIV epidemic and more. So all of the work through those offices. And the third line of work is more subjective. As a staff division of the Secretary's office, my office was a staff division as opposed to an operating division, which are a little bit more siloed. CDC, FDA, NIH, et cetera. I'm in arm of the Secretary. He would call upon us to pull together different strands throughout HHS or even the government, to work on specific issues. For example, Long COVID, climate change work, the syphilis work, but also sickle cell work, the nutrition work, and more. Often with no people and little money. And so, they congratulated me over and over again for doing, fulfilling all of the missions that we had to do with no people and no money. I guess it was a compliment. Eventually I was hoping it would lead to, I can do a lot more if I actually had some more people and some money, but not to be.

0:04:08 RL: So they called us the connective tissue of the department. I was personally hoping the beating heart of the department, but I got connective tissue, so that's okay. Those were my three line of efforts as the Assistant Secretary for Health.

0:04:20 DB: One of the remarkable things, as I listen to your remarks and think about your career journey, is that you've had success at multiple levels. And in part because of that success, new opportunity, and your openness to be able to step out of your comfort zone, to embrace that new opportunity. And so, I just would like to invite you to comment on that as our students are, much of their careers ahead of them and will find themselves perhaps in similar situations?

0:04:47 RL: Absolutely. I have always enjoyed and embraced change and transitions. Huh? And so I have really embraced having a steep learning curve and kicking myself out of my comfort zone. So whether that is going from 80th and first in Manhattan to rural central Pennsylvania, whether that is going from public medicine and in academic medicine to public service and public health, from going from Pennsylvania, nationally, taking on the uniform of the United States Public Health Service Commission Corps, for the Assistant Secretary, that's a choice. Surgeon General is always in uniform. But for me, it was a choice, and I really wanted to do that. And that was really one of the most meaningful aspects of my position. So I think it is very important for people to work to do that, to embrace change and to embrace opportunities, to step out of your comfort zone and to do something new. One example I will use, probably one of the times I really felt out of my comfort zone, making note of the weather, your lovely weather here today, was we went to Alaska and we went to Anchorage, which is a small city.

0:05:55 RL: But then we left Anchorage and we went to Nome. We went to the village of Savoonga, on Sivuqaq Island. We went to Kotzebue and Kiana, and then up to Utqiagvik, which is the top of the world. I was very much out of my comfort zone. The environment, the challenging living conditions, it was just, it was an amazing trip. But I always have relished that opportunity and I would encourage you to do that. You might think you know where your career is going, but if I was in academic medicine at Penn State, I know Penn State's a little controversial here, but anyway, I was at Penn State and doing all my missions. So I saw patients, I was teaching, I was doing clinical research, I was doing administration. Despite everyone recommending that I not leave to become the physician general of Pennsylvania. I just felt it was a unique opportunity and I jumped. And so, as my mother said, it led to something terrific.

0:06:45 DB: Terrific. In recent years, Washington has been an especially partisan political environment. And imagine that you had to work with people who didn't necessarily share the same perspectives as you. And so, I wanna just inquire about what some of the strategies that you use in trying to help work across various lines of difference?

0:07:06 RL: So, things have gotten much more partisan even from when I came. When I was in Pennsylvania, as I mentioned, I was unanimously confirmed twice and almost unanimously a third time. And I worked very closely with the Republican led legislature in Pennsylvania on public health issues. Now, we might not always agree on everything, but we could agree on a lot. And we did. I think that politics particularly started to become very prominent in public health during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. You saw that here in Michigan, in fact the protests at the State House, here in Michigan were one of some of the first public protests against COVID-19 mitigation efforts. And I think that that has led to a real split in public health from a partisan political nature and is carrying through even today. But I had a number of opportunities to meet with legislators of the other party, and to me, people would say, "How does it feel to be a politician?" I've never been a politician. I've never really considered myself to be a politician. Now I understand that the positions I were in are political nominated positions, but I've always considered myself a physician and public health leader.

0:08:14 RL: And in my opinion that shouldn't be political at all. But unfortunately it is. And so I think it is incumbent upon all of us to work across the aisle, to work across parties. None of the public health work we're talking about really in its heart is political at all.

0:08:27 DB: Prior to joining the Biden administration, you served, as you mentioned, as secretary of health and physician General in Pennsylvania. And how did working on public health at a state level differ from that at a federal level?

0:08:40 RL: Right. So it's interesting and you might not, people might not know this. But there's a certain bureaucracy to the federal government. Did you ever hear that? There is a certain bureaucracy in Pennsylvania as well, but that's kind of like the minor leagues. And then you go to the majors in the federal government, you go to the show, as they say, you have to work through that. And I had a great staff that would cut through either bureaucracy at HHS or throughout the federal government. And we work to get a lot done and try to work past that. Be honest with you, I did not find the public health issues that different from Pennsylvania to nationally. It's just that I had to pull back my scope instead of just looking at Pennsylvania's numbers or the Mid-Atlantic numbers, but to like with COVID or something, but to look across the whole country, whether we're looking at COVID-19 rates or vaccination rates, about overdose rates, about nutrition, about HIV or any of the issues that we were dealing with. One of the biggest differences though was my commission and taking the uniform of the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. That was something that again kicking myself out of my comfort zone that I've never experienced before. And it turned out to be one of the greatest honors that I had in the federal government.

0:09:56 DB: In the lead up to the presidential election last year, we saw in my view, just a disturbing amount of negative ad campaigns, particularly in battleground states like Michigan, I imagine Pennsylvania as well. And some of these included ads that had specific anti trans rhetoric. And in recent years we've also seen a growing number of states that have imposed restrictions on gender affirming care for young people. And so, I would like to invite your thoughts. What message would you deliver to the public in response to some of these emerging constraints on, in targeted activities in terms of healthcare?

0:10:37 RL: So, the ads were very difficult and very challenging. And many of them, most of them contain my face in those ads. So I have to tell you, I knew that my appointment would be controversial. I did not expect to be literally the tip of the spear of the culture wars of America. It was challenging. But I said in other interviews, I'm fine. I'm a pretty strong and resilient person, and I'm really fine. What I worry about is the impact of those ads on other people in the community and their families and their providers, and the challenges, particularly for young people and their families, to that rhetoric and that vitriol. I think it is important to note that, the laws that have passed in many states of the country targeting transgender medicine and targeting transgender people in general, are our response to a specific iterative strategy from conservative think tanks in Washington, to target our community in order to split the broader LGBTQIA plus community and to split the progressive community. And unfortunately, they were very successful. Many of the laws that passed come out of a specific cookbook. Often the people who were even introducing the laws didn't even know what they were quite introducing.

0:11:51 RL: They were handed a playbook, and they followed their playbook. It was, unfortunately tremendously effective, starting with trans athletes, then going on to transgender medicine for young people, and then transgender medicine and trans people in general, which is where we are now. And then, it wouldn't surprise me if they go on to the broader LGB community as well. Transgender medicine is an evidence-based, standard of care treatment. We have a lot of research that was going on in the United States, other countries. A lot of it's being curtailed right now, and it evolves over time, as do the medical standards of care for any medical treatment. Should it be better? Should there be more research? Yes. Can it get better? Yes. As treatment for diabetes has changed a lot in the last. Tremendously actually, for type 2 diabetes in the last 10, 15 years, especially now with GLP-1 medications, et cetera. So a tremendous change. And so there's been change in the care standards of care for young people as well. Most of that care is done at children's hospitals throughout the United States. And so, what I would ask the question, if you have a child with diabetes, you would probably go to the children's hospital in your city?

0:12:57 RL: So here you'd probably go to Michigan's Children's Hospital. If you have a child with potentially an eating disorder, you would go to the adolescent division in the eating disorder program at the Children's Hospital. If you have a child with depression or anxiety, you would probably see the child psychologist or child psychiatrist at the Children's Hospital. So if you had any medical condition, you'd go to that clinic. So if you have a child with gender issues, why are we involved with the state legislature? You would go to the gender specialist team at the Children's Hospital. I even had agreement with the AMA on this and spoke with Jesse Ehrenfeld, who was previous president of the AMA, at a conference for PFLAG for families of LGBTQI+ youth. Is that you're really getting in between a physician and a team and their medical provider and the young person and their parents.

0:13:48 RL: Because all this is with parental consent. And so, why are states prohibiting that treatment and not impacting the treatment for diabetes or other things? So I view it in that lens. Now, it is very much of a challenge in over half the country, where gender affirming care or transgender medical services are not available to young people. And they're trying to make that across the country, you have people like your attorney general and governors trying to stand up for that. And we'll see how things come out in the courts, and we'll see how things are. But it is very challenging right now for those young people, for their families who are just trying to parent their teenager and for their medical providers who have been threatened. We're gonna have to stand together. And again, I'm gonna... In the face of all that, I choose to remain positive and optimistic, but I'm extremely realistic and understand the challenges that we have now.

0:14:39 DB: Terrific. So you mentioned stand together. You're talking to an audience who believes in attainment of health for all. And so for those who wanna take proactive measures, what are some of the ways to combat the trends that you just discussed, and including healthcare for trans individuals?

0:14:55 RL: Well, I think it's important for public health professionals and medical professionals that all of us do stand together and continue to support health equity, which I've said before is fundamental to public health. This is not a new concept. Health equity in public health is not a brand new concept. And addressing the social determinants of health is not a new concept. And so, I think that we need to stand together in that. I think that we need to, as I mentioned in the LGBTQI+ community, to stand together as a rainbow family. And we need the help of our allies to stand together. 'Cause we are all stronger together. I think it's important not to have an emotional reaction, if possible, to the challenges that we're facing. And I know that's difficult, but I have often in my clinical training, learned to compartmentalize my emotional feelings when I need to do my work. So if I'm a pediatrician and this critically ill child or a teenager arrives in the emergency department, that can be extremely emotional, the parents, et cetera. Well, you can't let your emotions carry you away. You need to put it someplace, and then do the work that you've been trained to do as a physician or as a nurse, or as a social worker or anyone else.

0:16:04 RL: Well, we need to do that in public health as well, is be able to compartmentalize our emotions. Now you have to bring them out later with your friends and your family, however you process stress. But we need to do our work now. So I think that we need to do that. And I think we need to not make anticipatory changes. I don't think it is wise to make changes in anticipation upon what others might do or say, 'cause we don't know exactly what they're gonna do or say. And there are safeguards. Congress can be a safeguard, the courts can be a safeguard. You have governors and others in different states that can be a safeguard. So we do have safeguards and checks and balances in place. So I think it's important, not to make anticipatory changes based upon tweets and rhetoric. If a change has to be made legally, then I'm always recommending that we follow the law. But often in cases we're not there yet. We've just heard pronouncements that don't have legal weight. So we should not over anticipate and jump the gun and make changes that could hurt people or our communities in anticipation of what might happen in the future.

0:17:14 DB: So we received several questions at registration asking about some of the recent federal executive orders that you didn't name. But one of the things that I think are implied by your comments. And some of our attendees were wondering, as we've also seen pressure put on certain agencies, how do we make sure that health agencies can communicate with the public and share evidence-based information?

0:17:39 RL: Sure. Well, remember, there are three levels of government that we all have. There's local government, and local health departments, and there's state government and state health departments. And then of course, we have the federal government and our federal health department. So I think that state and local health departments need to continue to do their work. And I know many of them, and they will continue to do their work. And dealing with these political challenges is not new for my colleagues in many other states, in many red states. They're used to many of these challenges for the state and their health departments for Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi and Texas and Florida, et cetera. And so, there are ways to work through that. And so, I think that we need to learn from them and listen to them, whether they are in state or local health departments in other parts of the country, and to learn, well, how do they still do good public health in a challenging environment or an environment where health equity is controversial? I think we can learn a lot from them. And unlike some of the rhetoric that I've heard, I have to tell you that our civil servants in public health at the local, the state and the federal level are absolutely dedicated public health professionals. And I think that they're gonna do their work and continue their work as much as they possibly can. And I have faith in them.

0:18:56 DB: So another question that we had at time of registration just inquires about how women's care might be impacted. Are there things that we can do at a state level just to help ensure that women have access to reproductive care that they need?

0:19:09 RL: Oh, absolutely. The Office of Population affairs was under my purview, and the Title X program was under my purview, as well as preventing teen pregnancy, Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Program, and the small but mighty Office of Adolescent health. The Title X program, access to knowledge about reproductive rights and access to birth control, comprehensive sex education has been a victory in public health. The unintended pregnancy rate and the teenage pregnancy rate has consistently gone down since the '80s. It's remarkable. So we don't wanna lose that progress. And so, I think that it's gonna be to the states to be able to do that. In addition, is the right to abortion. And abortion is healthcare. It's essential part of the toolbox for reproductive healthcare for women. And I think that the states have an absolutely critically active role.

0:19:57 RL: In terms of providing that care to people who live in your state, but then also to people who travel to your state. And that's what's happening, is that women and families are coming to Michigan, they're coming to Illinois, they're coming to Maryland, they're coming to Colorado and New Mexico and California from other states to get the healthcare that they need and that they deserve. Michigan and other states are a bulwark for reproductive healthcare for women. There are concerns about other reproductive health care, including even the right to contraception. During, in the opinion from the Dobbs decision, the contributory opinion by one of the justices, there was even an allusion to Griswold versus Connecticut, which is the contraception law, which is from the, I believe that case was from the '60s and threatening that law. I think that it's important for us to be vigilant and to continue to advocate for the full range of reproductive health care for women and families.

0:20:52 DB: Terrific. I wanna follow up on your comment. As things vary across states, that also potentially introduces some challenges along the lines of health equity. And for some people who may have access to be able to cross state lines to seek care versus those who are not in a position to do so. So I'd like to just invite your comments about that as well.

0:21:13 RL: So the ability to seek care out of state is a health equity issue. 'Cause not everyone can afford to travel out of state. Now, if you're north of South Dakota, you might be able to go into Wisconsin, but if you're in Georgia, where are you gonna go? If you're in Florida? So you're gonna really have to drive a long way or you're gonna have to fly. And not everyone can afford to do that. It results in only people of means can actually get the health care that they need and deserve. And that is true now for transgender medical care. I think that's an enormous health equity issue that we should continue to work on. I don't see an easy. I don't see a quick solution right now, but I'm still optimistic for the future. The term I used, when I was the ASH Assistant Secretary for Health, was medical refugees. We have created medical refugees in the United States who have to leave their state to get the medical care that they need and they deserve. I think that's a shame. In the United States of America, we have medical refugees. And I think that's gonna get worse and then it'll get better.

0:22:17 DB: Certainly during the campaign season, you saw lots of misinformation. And I'm just wondering during your time as assistant secretary, I'm assuming that you've acquired a lot of experience dealing with information. And what are some of the most effective ways that you think in the field of public health, that we can work to combat misperceptions and to try to promote accurate information.

0:22:37 RL: We saw the impacts of misinformation and overt disinformation, even before the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and before I was in federal public health, and particularly about vaccinations. Now, the root of this comes from one of our own, the infamous Dr. Wakefield in England, who wrote an article in the early '90s stating that the measles vaccine had a relationship to development of autism. Now what it's turned out is that he fabricated that data and it was a spurious article and has since been withdrawn by the Lancet. It has since had numerous studies which has proven even, I know you work with big data and other people do epidemiology, from clinical trials to big data sets has been proven not to be true. But that has continued. And vaccine reluctance and vaccine hesitancy, it's actually not partisan. It's somewhere where the far left and the far right meet in Oz. And has been a challenge even before the pandemic and even before certain advocates have gained prominence. And so, we had no cases of measles in the United States in the year 2000. We also had very little cases of syphilis in the United States, but we had no cases of measles.

0:23:56 RL: And now we not infrequently see measles outbreaks, including right now one in Texas. And that's because of that misinformation and disinformation. So I think it is incumbent upon us in public health at all levels, whether you're local, state, federal or in academics, to counter that misinformation and disinformation with facts, not alternative facts, actually fact facts. And to continue to talk about the scientific facts that we know. Now, how we do that, I think needs to continue to evolve. I think that the field of public health communications needs to continue to evolve and to get better, to be able to counteract that misinformation and disinformation. So a question that I've been asked a lot, has been about social media and how to do that with social media. Well, you are talking to an out and proud baby boomer. And I don't know the answer to that question. I am not on social media, and I don't know the ins and outs of social media actually that well. And so, I will look to you all, people in public health, but the people in communications, who study social media. I know in adolescent medicine there are some specific people who study the impact of social media on adolescents.

0:25:19 RL: I will look to young people, by which I mean anybody younger than me, if you're not in your 60s, you're a young person. About how best to use social media. I don't know, but it isn't impossible. We Just need to study it better and to learn from it like we learn about everything else. What are the threads to pull to be able to do that? I don't know, but we should be able to figure that out.

0:25:42 DB: I take that as an assignment to some of the students in the room.

0:25:44 RL: Absolutely. Absolutely.

0:25:46 DB: So picking up, you mentioned the lingering vaccine hesitancy and how some of that is spurred by misinformation. There are instances though, where there's been mistreatment even by the medical community in the past, instances that we're seeing now, as I think about communities of color in the past, anti-trans, rhetoric now by way of the federal government. And so, I wanna really nail in on the importance of trust. At some point, as we move forward as a public health or medical community really trying to support healthcare needs, we will be left with that harm or breakdown in trust. And so, I would like to just have you, invite you to comment.

0:26:32 RL: Well, trust is absolutely critical in medicine, and it's absolutely critical in public health. And so, as a physician or other medical provider or mental health provider, you need to have this trust within the doctor-patient or doctor-client relationship. And I think it's critical in public health as well. And I think prior to the last five years or more, I think the public did have more trust in state and particularly federal public health, CDC, NIH, FDA, et cetera. I think that that has been severely damaged, particularly by the politicalization of the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. And so, I think trust has to be earned. And I think that it'll be incumbent upon us now or certainly in the future to earn back that trust. But this is not the first time we've had problems of trust. And you allude to human research that broke that bonds of trust, with the Tuskegee experiment, with other challenges, particularly I'm thinking of sterilizations that were done in the Indian Health service in the '60s and things like that. So many ways that medicine and public health broke the trust of people, particularly communities of color, but not exclusively.

0:27:43 RL: I think that we have to earn that back. I think we have to acknowledge it. I think we have to apologize for it, and I think that we have to then do better. And trust has to be earned. And it's our responsibility to earn back that trust.

0:27:55 DB: So we have time for one final question, and a lucky audience member actually at time of registration gets it. What would you say to an aspiring transgender leader who wants to run for the US House of Representatives in this political climate?

0:28:09 RL: Well, I would say, I would follow the path of Sarah McBride, who I know well has been elected to the House of Representatives as the representative from Delaware. And I saw her last week in Washington. And she's responding with grace under severe pressure, very, very tense, challenging environment. And she is responding with such leadership and grace that she's the future. And so, I would encourage you to continue to do that, to work on a political career. Public health and medical professionals can certainly go into politics. I don't think that I went into politics. I've never been elected to anything, but I think that that would be a very valid political career, and I think it can be done. Now, I probably wouldn't go to Texas to get elected, but if you're here in Michigan or you're in Massachusetts or California or obviously Delaware or certain parts of Pennsylvania and certain other areas in our country and Colorado. Then I absolutely think that you could get elected to local, statewide, and even federal public office. Young people are our future, and I think that we need to not respond to the current environment with fear.

0:29:26 RL: I think that we need to get past our fear, and to do the right thing. What I'd often tell my staff both in Pennsylvania and here, is that when in doubt, we need to do the right thing. Now you got to figure out what the right thing is, and that's not easy all the time. But when you do, don't be afraid to do the right thing and continue to work for the common good.

0:29:47 FB: Terrific. So I wanna, in closing, thank you for your expertise and the diligence that you take to your work. Thank you for choosing a path to serve the public, and then thank you for your courage. Will you please join me in thanking Dr. Levine.

[applause]

[music]

0:30:14 HOST: Thanks for listening to this episode of Population Healthy from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. We're glad you decided to join us and hope you learned something that will help you improve your own health, or make the world a healthier place. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe or follow this podcast on iTunes, Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. Be sure to follow @umichsph on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, so you can share your perspectives on the issues we discuss. Learn more from Michigan public health experts and share episodes of the podcast with your friends on social media. You're invited to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get the latest research news and analysis from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Visit publichealth.umich.edu/news/newsletter to sign up. You can also check out the show notes on our website, population-healthy.com for more resources on the topics discussed in this episode. We hope you can join us for our next edition where we'll dig in further to public health topics that affect all of us at a population level.

[music]

Related Content

Explore the topics discussed in this episode further with our curated list of resources. We've compiled relevant materials mentioned in this episode so you can dive deeper into the conversation.