Silver linings

Critical knowledge gained from COVID-19 pandemic proves invaluable to alumni

Amy Crawford

It felt like everything happened at once.

At first, the pandemic was far away. Then, all of a sudden, the Detroit area had become a hot spot for a disease that had only just been named COVID-19, and Denise Brooks-Williams, MHSA ’91, was on the front lines of a global pandemic.

“It definitely was a fast build,” said Brooks-Williams, senior vice president and CEO, North Market, with Henry Ford Health. “There were so many things we didn’t know at the time. Was it airborne? Did it live on surfaces? Now, we can get test results in an hour, but that wasn’t the case then.”

As the state shut down everything from restaurants to schools, Henry Ford, which has hospitals and medical centers throughout Michigan, postponed elective procedures, and restricted visitors for the health and safety of employees and patients. Efforts would be focused on treating the deluge of COVID-19 patients with constant adjustments to procedures and protocols as scientists learned more about the virus and health care providers adapted to changing conditions.

I think there will be a lot of positive things that come out of this.

-Denise Brooks-Williams, MHSA ’91

“Our supply chain team was good about providing regular updates on our PPE supply and other supplies that we were burning through like never before. Every day our leadership team would do an evening huddle, where we would ask ourselves, what do we need to do different or adapt to continue to keep our team members safe?” said Brooks-Williams, whose jurisdiction includes two acute care hospitals and 70 clinical sites across Oakland and Macomb counties.

Looking back on those early weeks in the spring of 2020, Brooks-Williams is proud of her entire team, some 8,000 health care providers and support personnel who met the crisis head-on and held it together for their community during extraordinary times. But as the pandemic stretches into its third year, she is also looking to the future and to new and ongoing challenges that must be faced and overcome.

I wouldn’t expect my team to do something that I wouldn’t do myself.

-Richa Gupta, MHSA ’02

Across the country, the pandemic put stress on the health care system, revealing both its strengths—heroic providers and adaptability in the face of uncertainty—and areas where it must improve. And no one was better situated to learn these lessons than the executives working to steer hospitals and health systems through COVID. From recruiting and retaining the doctors, nurses, and other essential workers who keep hospitals running, to reimagining their business model, these leaders are already thinking about how health care will look after the pandemic and how we can prepare for the next one.

‘Defining moment for Rush’

Most hospitals had to improvise as they pivoted to pandemic care. Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center was built for it from the beginning.

Planned and constructed in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the anthrax-laden

letters sent through the US Postal Service in the weeks afterward, and the 2003 SARS

outbreak, the butterfly-shaped building known as Rush Tower has 39 negative pressure

rooms to help contain aerosolized pathogens. Its emergency department (ED) is divided

into three 20-room pods, each of which can be converted to negative air pressure to

isolate infectious patients from other emergencies. Additional spaces can be quickly

converted for triage and patient care during “surge mode,” when Rush Tower is expected

to accept transfers from around the city.

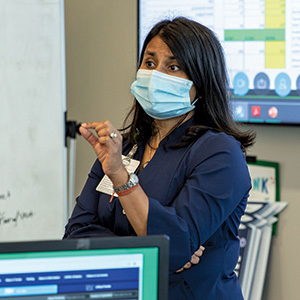

But even with all that preparation, the novel coronavirus presented plenty of unknowns, said Richa Gupta, MHSA ’02, senior vice president of clinical operations and chief operating officer at Rush University Medical Group, who has led Rush’s pandemic response since March 2020.

“While we were built to handle something like this physically, the real challenge was preparing the people who worked in the buildings to be ready for this,” she said. “This was a defining moment for Rush. Being a leader during a pandemic is really a big risk to take, but I’m really thrilled that we took that risk. We knew we wouldn’t always make perfect decisions, but we made the best decisions we could with the information that we had.”

Gupta brought an astounding level of energy to her role, putting in 14-hour days in the Rush “command center” with a leadership team of about a dozen others who oversaw physicians, nurses, facilities, communications, infection control, and other key elements of Rush’s pandemic response.

For Gupta, leading by example was key.

“I wouldn’t expect my team to do something that I wouldn’t do myself,” she said. “The whole team was willing to sacrifice a lot of time with our families to be there, to make sure that all of our decisions were made as quickly as possible, and that they were cascaded through the system just as quickly.”

Trained as a physician in Mumbai, India, Gupta realized during her internship that practicing medicine was not for her and she came to the University of Michigan School of Public Health looking for another way to improve health care outcomes. It was not until the pandemic, however, that she truly realized the importance of leadership and the difference that administrators can make in patient care.

“We saw how our decisions could save lives,” Gupta said. “Sometimes, it can feel like you’re just managing a business, but you’re really in this to improve lives, or I am, anyway. And there’s really been no better time to be an administrator. It calls on problem-solving skills and change management in a way that we’ve never had to do before.”

Finances impact patient care

Of course, managing the business side of health care is crucial because finances also have an impact on patient care. That’s a pandemic lesson that became all too real for Bill Manns, MHSA ’91, who took over as president and CEO of the community-owned, not-for-profit Bronson Healthcare in March 2020.

An irony of that spring was that even as hospitals were deluged with patients, many

faced staggering financial losses because elective procedures and routine care were

postponed. Bronson has 100 locations throughout southwest Michigan; it’s not only

the region’s primary resource for medical care but also its largest employer. So when

the system faced a $15 million budget shortfall in March 2020, there was more at stake

than money.

“I knew the organization couldn’t lose $15 million a month and survive,” Manns said. “It’s the balance of running a health system; there’s an old adage, ‘No margin, no mission.’ You can’t care for the community if there are no resources. So this was a story about, ‘How do you preserve the mission by protecting the margin of the organization?’”

Manns was facing an additional challenge. Formerly the president of St. Joseph Mercy Hospitals on the east side of the state, he had accepted the top job at Bronson just before the pandemic hit, which meant he had to get to know a new system, new colleagues, and a new town—all while managing the greatest crisis of his career.

“Bronson had a robust welcoming plan to integrate my family and me into the community,” Manns said. “That went up in smoke because the public health profession couldn’t support having large gatherings. Meanwhile, I had moved into a new condominium and we’d started work on it, but the governor shut down construction so the place was half-finished with debris and things all over. I had to do a little bit of electrical work and some plumbing myself just to make it habitable.”

He wasn’t spending much time at home, though. Instead, Manns was busy getting to know his leadership team, learning about their personalities and skills. He also worked to bring them together around the system’s operations and financial situation, making it clear that he was open to their thoughts about how things could be turned around.

“We actually asked about a hundred leaders for their ideas and what they thought we could do differently to improve the financial performance of the organization,” Manns said. “We sorted those leaders into small teams and we asked questions and got their answers on a weekly basis—it was important to be transparent. Each team could see what the others were working on, with the best and brightest ideas bubbling up from those who were closer to operations.”

Manns also asked key physician leaders to serve on an advisory team that reviewed the proposals for potential impact on quality of care and clinical workflow, while identifying additional ideas.

Voluntary salary reductions for Manns and other executives were an obvious first step, but Manns wanted to find revenue through growth rather than cuts. The system had recently partnered with a large primary care group to add seven new locations and needed to ensure that these new patients were able to access Bronson system resources. Advances in telehealth offered new ways to serve patients without exposing them to the coronavirus. And by consolidating the command center for Bronson’s four hospitals, the system was able to streamline its resources while making crisis management and communication more effective.

“We did some things that really helped us bounce back while creating a growth mindset,” Manns said. “Our people found revenue and opportunities that went well above anything that I would’ve expected, and we were able to really stabilize the organization financially.”

By the summer of 2020, health care leaders were already beginning to think in terms of what they called the “new normal.” They knew the first wave of the pandemic would not be the last, but, at the same time, it had highlighted so many other areas that were ripe for change.

“I think this is a tipping point for health care,” said Gupta, arguing that the pandemic has driven home the importance of shifting the industry’s financial model. Historically, hospitals have run on fee-for-service, which is why canceling elective procedures during the pandemic sent so many into the red. In recent years, however, health care has begun to transition to a value-based system that looks at longitudinal outcomes for patients instead. Such a structure ought to serve patients better, but change can be frustratingly slow.

“There are a lot of fiscal and quality arguments to be made on both sides of this debate, but I think it’s important that we all align on this, rather than continuing to have a foot in each canoe.”

Limited pool of health care workers

A more immediate problem, however, is staffing shortages. At Rush, administrators are working out the best way to deploy everyone from doctors to medical assistants, with a goal of “the right work by the right person in the right place,” Gupta said.

Meanwhile, hospitals around the country are competing for a limited pool of health care workers at every level.

“There’s a wage war for staffing right now,” Gupta said. “And this gets back to administrators. How we equip our leaders to support our staff on a daily basis is what makes the difference for staff engagement. I have heard directly from staff that it’s when you don’t feel that engagement or respect, that they will leave for a dollar or two more an hour.”

Staffs are also experiencing the effects of burnout. After nearly two years on the front lines of a pandemic, workers at every level are exhausted and demoralized.

“My team that directly reports to me, they’re hospital presidents, chief medical officers, nursing officers,” Brooks-Williams said. “They’re incredibly high-level professionals, but we had people get COVID. We have sometimes cried together. We definitely prayed—a lot. We became incredibly close, of course, because we had to support and rely on one another, but it took us getting out of the first wave to begin to talk about resiliency and support.”

For Brooks-Williams and other health leaders, these “softer” elements of leadership have emerged as among the most important parts of the job.

We’ve got caregivers who have given their all. How can we give back to them?

-Bill Manns, MHSA ’91

“One way is, we’ve increased our mental health benefits for our employees and their families.”

Manns and his team are also considering a concierge service for employees to help alleviate stress and shorten their to-do lists by, for example, picking up their laundry or catering their lunch.

Child care has been among the biggest stressors, and one that has had an impact on health care systems’ ability to maintain staffing levels. With frequent school closures and a shrinking pool of daycare providers, working parents have struggled to find consistent care during the pandemic.

Bronson partnered with the YMCA to provide care for essential workers’ kids during the height of the pandemic, but Manns knows that the childcare issue is not going away and it’s not something that employers can continue to expect parents to navigate on their own.

Positives from COVID

A health care system exists within the context of its community, and the pandemic made it clear that the relationship must extend beyond the hospital doors. In the Detroit area, for example, the Black community was especially hard-hit, and when Gov. Gretchen Whitmer created the Michigan Coronavirus Task Force on Racial Disparities in April 2020, Brooks-Williams was an appointee.

“What we could see is the death rate might have been higher because African-Americans were delaying coming to the hospital,” Brooks-Williams said. “We had poor testing at the time, so people didn’t know what they had, they didn’t know what to do at home, and they didn’t have an established relationship with a provider who could guide them through it.”

The task force called for more testing in the community, and Henry Ford Health helped by establishing drive-through and mobile testing sites in neighborhoods that had been underserved.

“Then, we also put together what we called ‘COVID kits,’” Brooks-Williams said. “These would go to people who didn’t need to be admitted, but did need to isolate.”

The kits included masks to help people avoid spreading the virus to their family members or roommates, as well as thermometers and pulse oximeters.

“What we found is when people went home, they didn’t always know when they were not faring well because COVID can get worse—fast!” Brooks-Williams said. “We would send them home with a pulse ox so that they could monitor their blood oxygen, and if they dropped below a certain number, then that indicated they should come back to the ER immediately or call 911. We believe it contributed to saving lives.”

The pandemic has led to important medical breakthroughs, improving scientists’ understanding of airborne viral transmission, for example, and furthering the technology of MRNA vaccines, which has already led to advances in longstanding wars against other pathogens.

Brooks-Williams and others who have led hospital systems through the worst pandemic in more than 100 years, however, also know that the most effective strategies for getting through a crisis are often the least flashy—supporting caregivers and their community, empowering people to care for themselves and one another, and seeing patients and providers in all their complex humanity.

“When we catch our breath and get a chance to pause, I think we’ll be able to create some change for the good,” Brooks-Williams said. “I think there will be a lot of positive things that come out of this.”