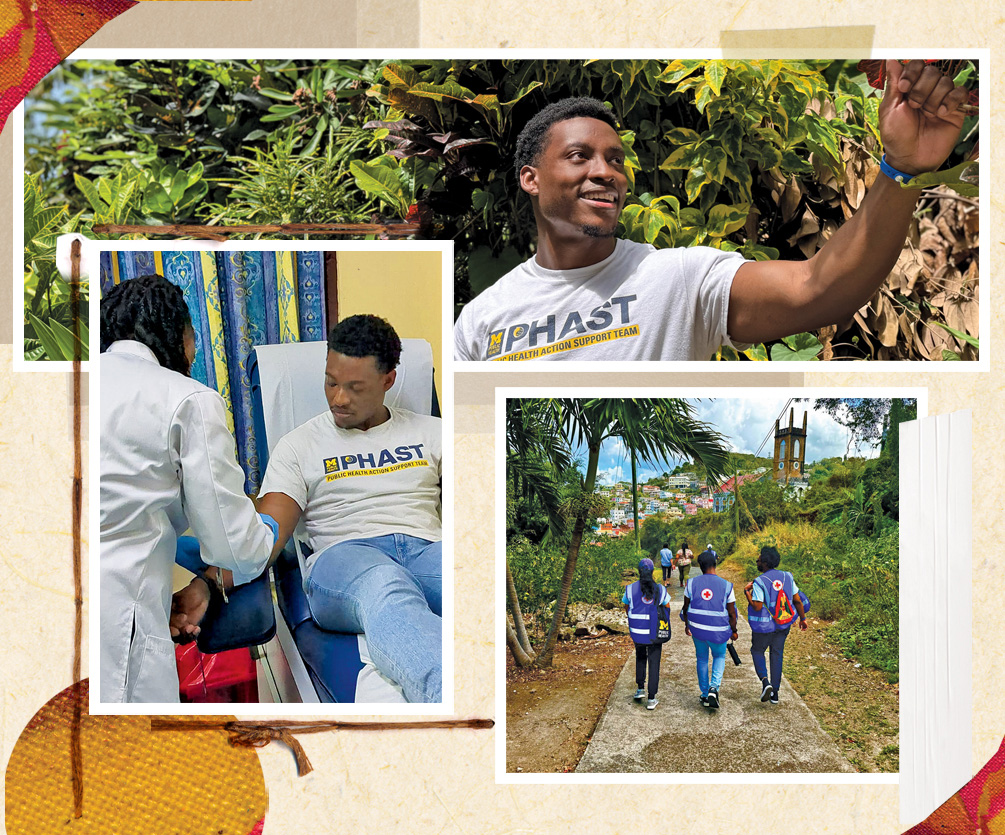

On a PHAST track

Public health students’ experiences beyond the classroom prepare them for success

By Bob Cunningham

Darius Moore, MPH ’24, has always focused on health equity in everything he does, whether it’s in the classroom or in his work and research interests.

In February, Moore put his beliefs into action when he donated blood to the Blood Bank of Grenada, experiencing firsthand the importance of community engagement in public health.

Moore and 14 classmates from the University of Michigan School of Public Health traveled to the Caribbean nation to participate in the annual experiential learning project through the school’s Public Health Action Support Team (PHAST). During spring break, his team spent a week working with the Grenada Red Cross Society on a new project to establish a voluntary, unpaid donation model for blood donation on the island.

The process was swift, taking only about 30 minutes—and Moore’s impact was even quicker. Minutes after his blood donation, a medical professional urgently needed his O-positive blood for a patient.

“They literally pulled it out of the fridge and took it to screening right away,” Moore said. “It felt incredible to see in real-time how my donation was used to potentially save someone’s life.

“It was really impactful for me because I got to see the whole process of it benefiting someone else, and it felt good to do that. Initially, I wasn’t going to donate because I didn’t want to delay the team, but something inside me urged me to go ahead. I’m glad I listened to that voice because the Red Cross didn’t have any other O-positive blood at the time, and who knows what the outcome would have been otherwise.”

PROSPECTIVE STUDENT? Learn more about Michigan Public Health.

Moore’s experience highlights the stark contrast between Grenada’s current blood donation system and the more systematic approach seen in countries such as the United States. In Grenada, the family replacement model is prevalent—people must find their own blood donors during emergencies. This process is often time-consuming and uncertain, which can lead to critical shortages and reliance on imported blood.

Experiential learning is key

Michigan Public Health provides students with hands-on experiences that prepare them for impactful careers. PHAST is a keystone of this experiential learning in the school’s Office of Public Health Practice.

One of the program’s most impactful partnerships is with Grenada. Since 2013, students have traveled to the island to collaborate on various public health initiatives. These projects range from setting up surveys for the Grenada Planned Parenthood Organization to assisting in disaster response and recovery.

Led by Dr. Laura Power and Sadé (Richardson) Mulkey, PHAST ensures that students connect with the communities they serve, both locally and internationally.

Power, an infectious disease physician and a clinical associate professor of Epidemiology, emphasizes the value of experiential learning.

It felt incredible to see in real-time how my donation was used to potentially save someone’s life. It was really impactful for me because I got to see the whole process of it benefiting someone else, and it felt good to do that.”

— Darius Moore, on his blood donation

“What really stands out is the applied experience for students and the connections to partners,” she said.

Power, who is the director of the practice office, underscores the importance of students seeing how their classroom learning translates into real-world action. PHAST trips allow students to apply theoretical knowledge, from engaging in community-based surveys to assisting in health policy formation.

Mulkey, a former PHAST participant and now the director of strategic initiatives in the practice office, highlights how these experiences redefine educational boundaries.

“Nothing goes in that nice, clear-cut framework you learn in the classroom,” she said. “It’s about getting your hands dirty and realizing the impact you can have on real people with real stories.”

The annual trip to Grenada is the culmination of the Public Health in Action course Moore and his classmates took in Fall 2023. The course prepares students through weekly lectures focused on community engagement, ethical research practices, and understanding Grenada’s demographics, history and economy. Moore’s team was tasked with helping the Grenada Red Cross Society develop a voluntary, non-remunerated blood donation system.

The team’s mission involved understanding local perceptions of blood donation through a combination of community surveys and critical informant interviews.

“We wanted to see how everyday people in Grenada felt about donating blood, their concerns and what would motivate them to donate,” said Moore, now a doctoral student who earned his Master of Public Health degree in Health Behavior and Health Education in May.

Moore’s team engaged with people in their everyday environments, such as spice markets, schools and police stations.

“Interacting with community members on the ground had its challenges, but it was about making the academic information accessible and practical for people,” he said.

Advancing public health initiatives in Grenada

When the 15 students of PHAST, along with Power and Mulkey, made the trip to Grenada, they were split into three teams of five, and each had a specific mission to work with a local community partner.

In addition to Moore’s group, one team focused on Alzheimer’s and dementia care. Another team worked on creating a disabilities affairs unit within the Grenada Ministry of Social and Community Development, Housing, and Gender Affairs.

For the Alzheimer’s and dementia care initiative, Global Epidemiology student Allison Baumgartner gathered insights and recommendations through focus groups and vital informant interviews with people with disabilities, their caregivers and other stakeholders.

It was the first time Baumgartner conducted in-person interviews, and soon the depth of the caregivers’ dedication quickly became apparent.

“It was amazing to see how caregivers, whether formal or family members, were deeply committed to providing dignity and quality care for their elderly loved ones,” she said. “They were eager to learn more and improve their caregiving skills, which highlighted the importance of our work.”

This trip also prepared Baumgartner for her summer internship in Bangladesh, an eight-week immersion near the capital city Dhaka, where she worked on maternal and child health.

“The skills I developed in Grenada, such as conducting interviews and engaging with community members, were invaluable for my internship,” she said.

Anisah McEwan, who graduated in May with a Master of Public Health degree in Health Behavior and Health Education, led the initiative to create a comprehensive care plan strategy for the Grenadian government. This plan aims to integrate insights from previous surveys and studies on the island’s aging population and their caregivers.

McEwan’s team partnered with local organizations and conducted focus groups and interviews in familiar and accessible settings, creating an atmosphere of trust and cooperation.

“We were able to conduct interviews at local disability advocacy groups’ offices, which helped build rapport with participants,” McEwan said.

A highlight of McEwan’s trip was the opportunity to deeply engage with the Grenadian community.

McEwan found that her classroom learning translated effectively into her work in Grenada. For instance, the socio-ecological model helped frame the complex interplay of factors affecting individuals with disabilities.

“I was able to implement theories and techniques from my studies in a real-world context, which confirmed the value of my education,” said McEwan, whose experience in Grenada solidified her commitment to community health. “Being out in the community, meeting people, and understanding their needs was incredibly energizing for me.”

Baumgartner concurs with McEwan’s assessment.

“Putting people and communities at the center of public health work is essential,” she said. “We’re not just gathering data—we’re building relationships and working alongside communities to uplift and support their needs. It’s about being present with the people you’re working with, understanding their needs, and using your skills to help make a positive difference.”

The beginning of PHAST

As one of the student co-founders of PHAST, Rohan Jeremiah, MPH ’06, a former Paul D. Cornely Scholar and Postdoctoral Fellow of Ethnicity, Culture and Health, has witnessed and contributed to the program’s growth since its inception in 2005. From his time as a student to his current role as a consultant, Jeremiah’s journey with PHAST showcases the impact of experiential learning in public health.

PHAST began as a concept during Jeremiah’s time as a Master of Public Health student. Working alongside faculty members Matthew Boulton, now the senior associate dean for Global Public Health, and JoLynn Montgomery, then professor of Epidemiology, Jeremiah and a group of about 15 students sought to link classroom knowledge with real-world public health practice.

Initially, PHAST focused on disaster preparedness and response, leveraging training from the Centers for Public Health Preparedness and Response, established by the CDC in the aftermath of 9/11. The program’s first major deployment came in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, where students were stationed in Louisiana and Mississippi to support recovery efforts.

Jeremiah’s commitment to PHAST didn’t end with his graduation. He continued to be involved, driven by the program’s significant impact on students and communities.

“Seeing the real-world impact and the professional development it offered made me want to stay involved,” he said.

Before enrolling in Michigan Public Health, his experience as a US Peace Corps volunteer had already shown him the value of fieldwork in understanding public health.

Over the past 20 years, PHAST has evolved from a volunteer-driven initiative to an integrated component of the public health curriculum, allowing students to earn academic credit for their participation. This structured approach has enhanced the program’s ability to provide meaningful experiences and has fostered a new generation of public health professionals.

Jeremiah’s ties to Grenada are both professional and personal. After earning his MPH, he moved to Grenada to join the faculty of St. George’s University School of Medicine. His family’s roots in Grenada helped him assimilate quickly, and he eventually spent five years working there, building significant relationships and contributing to public health initiatives.

In 2012, after returning to the US for a postdoctoral fellowship at Michigan Public Health, Jeremiah was approached by Dana Thomas, then a program manager in the practice office, about extending PHAST to Grenada.

“It was a natural fit,” Jeremiah said. “Grenada is close, English-speaking, and I had built strong connections there.”

By 2013, PHAST had begun its annual trips to Grenada, focusing on projects aligned with the community’s needs.

One key factor that makes PHAST successful is its focus on community needs. Jeremiah underscores that projects are always driven by what the local agencies want for their service population, ensuring the work is genuinely beneficial.

Public health is inherently an interdisciplinary field. You need people to tell the story and others to provide the information to tell that story. This program forces students to understand how these different perspectives come together to create a more comprehensive solution.”

— Sadé (Richardson) Mulkey

“We ask our Grenadian partners what their priorities are and tailor each PHAST project to meet those needs,” he said.

Over the years, PHAST projects in Grenada have included developing updated school drug and alcohol policies and supporting domestic violence shelters.

Today, Jeremiah continues to consult for PHAST, helping to conceptualize projects, maintain relationships and ensure continuity. His role involves preparing students for fieldwork and offering cultural insights and practical advice to promote smooth transitions.

“I participate in classroom lectures to discuss project expectations, cultural norms and community partner overviews,” he said.

Jeremiah’s involvement in PHAST has had a profound impact on his own career.

Now a professor and associate dean for Global Health in the College of Nursing at the University of Illinois Chicago, he continues to leverage his experiences with PHAST to inform his work.

“Maintaining a robust portfolio of global health practice alongside my research has been incredibly rewarding for my scholarship while enhancing public health infrastructures in Grenada,” he said.

SUPPORT research and engaged learning at Michigan Public Health.

An unparalleled opportunity

It’s clear PHAST’s strength lies in its interdisciplinary approach. Students from the school’s six public health disciplines—Epidemiology, Health Behavior & Health Equity, Environmental Health Sciences, Health Management & Policy, Biostatistics, and Nutritional Sciences—work together, merging their knowledge and complementing each other’s strengths.

This collaboration reflects the real-world necessity of integrated public health solutions.

“Public health is inherently an interdisciplinary field,” Mulkey said. “You need people to tell the story and others to provide the information to tell that story. This program forces students to understand how these different perspectives come together to create a more comprehensive solution.”

The success of PHAST is made possible through generous donor support.

We wouldn’t exist without it.”

— Dr. Laura Power, on donor funding

“We wouldn’t exist without it,” said Power, citing that donor funding is crucial for covering travel expenses and logistical costs associated with these trips and allowing students to focus on their work and learning.

For Michigan Public Health students, PHAST offers an unparalleled opportunity to connect classroom learning and real-world application. By working directly with communities, students will continue to gain valuable skills, build confidence and develop a deep sense of empathy well into the future.

Through this hands-on experience, they are not just learning public health—they are living it.

Handmade paper and painted journal art by Roland Benjamin of Harvest Studios in Grenada.