The first line of defense

Investigating the spread of fungal infections due to climate change

By Matt Markey

Photos by Yuan Zhu

Jennifer Head probes the darkest corners of the microscopic world, focused on a particularly devilish group of bad actors—ones that can essentially steal the breath of life from their victims.

Fungal pathogens are often somewhat of an apparition, an unexpected and seemingly invisible opponent of good health, until they are exposed under a laboratory lens or on a chest X-ray.

Head is helping to compose the book on understanding these potent vectors of disease, which sometimes can be misdiagnosed as pneumonia, tuberculosis or cancer.

She hopes to see an increase in the healthcare community’s awareness of their fingerprints and the dangers these pathogens can pose to everyone, especially those people who are most at risk.

Specific fungal threats

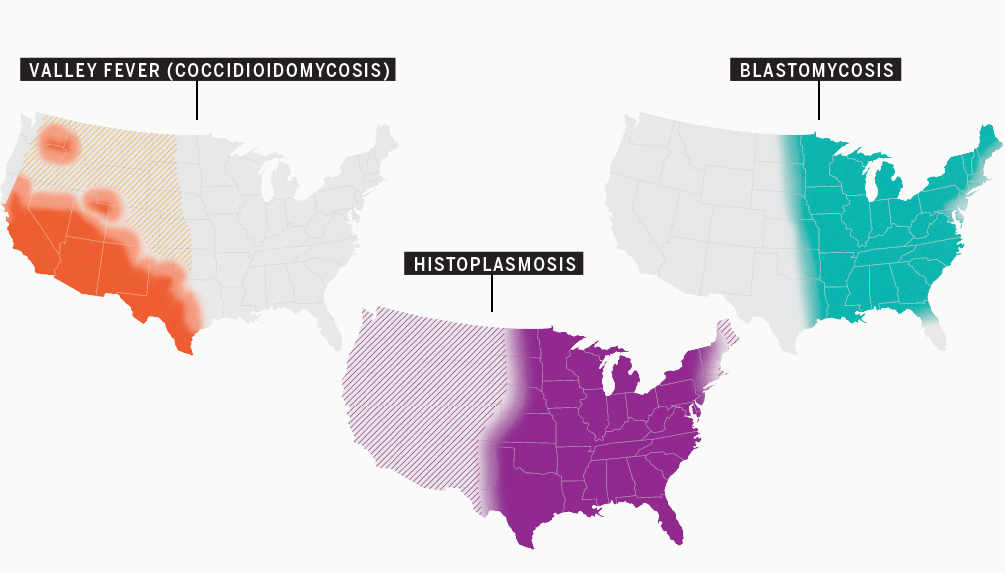

Head, the John G. Searle Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, focuses primarily on a trio of fungal infections: valley fever, histoplasmosis and blastomycosis.

While rarely mentioned in the general health news and often overlooked by medical personnel, these pathogens pose real risks to human health. Living in soil or decaying wood, they can be carried airborne and commonly attack the lungs after an individual inhales their spores.

All three of these fungal contagions can lead to acute respiratory distress and other serious complications. Although most manifestations are pulmonary, the spherules from the fungus can disseminate to other parts of the body.

INTERESTED IN A DEGREE from Michigan Public Health? Learn more about our programs.

Climate change and disease spread

Due to a rapidly developing unholy alliance with the ever-changing climate, Head said the fight against these pathogens is getting more complicated and the battlefield is expanding.

The geographic corridors where these diseases have been most prevalent historically are now tougher to configure as climate change stretches the map. And as the fungal pathogens are broadening their footprint, they are likely presenting a much larger threat to the health of a greater portion of the public.

“Every fungal species has an environment where it prefers to live, but we have seen dramatic increases in these diseases in some areas, and we’ve seen them expand into regions where they had not been detected previously,” Head said. “They were thought to have these very clearly defined endemic zones, but climate change is making those zones much harder to determine.”

READ MORE about faculty, students, alumni and staff.

“Every fungal species has an environment where it prefers to live, but we have seen dramatic increases in these diseases in some areas, and we’ve seen them expand into regions where they had not been detected previously. They were thought to have these very clearly defined endemic zones, but climate change is making those zones much harder to determine.”

Geographic distribution and risks

Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) gets its common name from California’s San Joaquin Valley, where it was initially identified. Its spores are present in the arid soils of the grasslands in that agricultural region. When inhaled, valley fever’s spores can bring about extreme fatigue, cough and fever.

Histoplasmosis is more common in the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, and its spores are most often found in the disturbed soils of construction sites or in the droppings of birds and bats. The symptoms of histoplasmosis are often tougher to identify, but it can produce long-term shortness of breath, fever, persistent cough, and, in some cases, the pathogen damages the eyes, causing scarring and the potential loss of vision.

Blastomycosis is most often found in the southeastern and south-central United States and in the Midwest, including a few hundred cases identified annually in Michigan. In 2023, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula had the largest outbreak ever reported at more than 100 cases. Blastomycosis hides in decaying organic material such as leaves and wood, and in the soil. While blastomycosis can be asymptomatic in some cases, in others it can develop into a severe pulmonary illness that is life-threatening.

Head sees a big picture, public health issue with this class of infectious agents, since the significant risks they present are not limited to people who are immunocompromised.

“While many fungal pathogens require their host to be immunocompromised to cause disease, this set of environmentally transmitted fungal pathogens can make otherwise healthy individuals sick,” she said.

Head said while many cases of disease caused by fungal pathogens are misdiagnosed, epidemiologic modeling of valley fever in California has shown a likely link in that suspected relationship between a changing climate and the increase in infections across a broader area.

“California and other western states are seeing dramatic increases in valley fever, and we hypothesize that much of this increase is related to climate,” she said.

She added the fungus requires moisture to grow, and within the traditionally endemic region, researchers have seen the highest incidence of disease following wetter-than-average years.

But the fungus also likely requires heat and dryness for the spores to spread. In previously wetter and cooler areas that are becoming hotter and dryer, the pathogen may now have increased ability to spread. Dryer soils are more easily eroded by wind, leading to more dust that may contain airborne spores.

“We’ve seen increases of over nine-fold in instances of valley fever in California over the past two decades,” Head said. “But even more concerning is that when we look at some areas which have been historically cooler and wetter, we see increases of over 15-fold.”

SUPPORT research and engaged learning at Michigan Public Health.

Climate change fuels valley fever

An increasingly large area of the Southwest could now see cases of valley fever, she said. As the habitat suitable for the pathogen is evolving under a changing climate, that can make scientific studies of valley fever more difficult, since the area of study is often a moving target.

“Tracking the emergence of diseases—and understanding the role of climate in that emergence—is especially challenging if we don’t have surveillance platforms in place to capture cases in new areas,” Head said.

“As an example, valley fever may be expanding eastward into Texas, but we have very little information on where and how fast it is expanding since there is no valley fever surveillance system for that state. As a result, we are limited in our knowledge of how to communicate the risk to people in Texas, and healthcare providers may not be likely to consider valley fever as a potential diagnosis.”

As the Southwest endures longer, hotter summers, more instances of valley fever also are showing up along the coast west of California’s San Joaquin Valley and in the plateau areas of Arizona that previously had not provided the virus with a suitable habitat for growth. The fungus needs heat for the fungal filaments to fragment and more easily disperse in the air, and the hotter, drier summers have provided that ideal brewing environment.

“With climate change, precipitation is becoming more variable, meaning there are periods of extreme drought followed by intense atmospheric rivers. The influx of moisture during wet winters may give the fungus the moisture and nutrients it needs to grow, and the hot and dry summers that follow allow the spores to spread. California, for instance, sees especially big spikes in cases when there is a wet winter followed by a hot, dry summer."

“With climate change, precipitation is becoming more variable, meaning there are periods of extreme drought followed by intense atmospheric rivers,” Head said. “The influx of moisture during wet winters may give the fungus the moisture and nutrients it needs to grow, and the hot and dry summers that follow allow the spores to spread. California, for instance, sees especially big spikes in cases when there is a wet winter followed by a hot, dry summer.

“When a drought precedes the wet winter, the spikes are especially large. We don’t know exactly why this is, but one theory is that the other fungal competitors in the soil die off during drought, giving the pathogen a relatively competition-free soil in which to grow.”

While doing doctoral work at the University of California at Berkeley during the early stages of the tracking of valley fever, Head saw the impact the fungal malady can have as her work moved from the confines of the laboratory to field research in California’s Central Valley.

“It helps you contextualize the transmission patterns better when you can see the actual locations where the pathogen is living and observe the sources of potential soil disturbance in and around population centers,” she said.

“When we went to Bakersfield in the heart of the [Central] Valley, nearly every person we talked to had a story about how they or a friend, family member or pet was affected by valley fever. This motivates me to contribute more to this field of study.”

Personal motivation and future directions

Head took a somewhat roundabout pathway to her status as one of the preeminent voices in the effort to address diseases associated with fungal pathogens and the increasing role climate change likely plays in their spread.

The Cincinnati native studied chemical and environmental engineering as an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis. She was inspired after family vacations to national parks across the American West in her youth had exposed her to a wide diversity of landscapes and environments.

“I fell in love with nature, and I was interested in doing something to protect the environment,” she said.

It was later, while working with Engineers Without Borders USA in Ethiopia, addressing water distribution issues at a school for people who are blind, that Head’s career course began to take a significant shift.

“I became more and more interested in public health as a field,” she said. “I hadn’t considered it before, but I found that the far-reaching impact that public health work can have really interested me.”

She said increasing the awareness of these fungal diseases is essential, since there is no vaccination currently available and respiratory protection, such as wearing N-95 masks, is not practical for workers in the construction and agricultural trades in areas with sustained intense heat.

Head favors more study and expanding the bank of knowledge about this group of pathogens that seems to be finding new favorable areas where they can proliferate.

“There’s a lot of evidence to suggest that climate change is responsible for the spread of valley fever throughout California as well as other parts of the southwestern United States, and we need to better understand the mechanisms behind the increases in incidence,” she said. “We also need a better understanding of how the risk to humans will change due to climate change.”

Head believes that before vaccines are developed and see widespread use, the best protection is knowledge of the likelihood of exposure. The sooner someone who displays symptoms gets diagnosed, the better the outcomes will be, she said.

I’ve continued to be interested in fungal diseases because there are a lot of mysteries that remain to be solved, and I feel positioned to help solve them.”

“Dealing with fungal pathogens and the associated diseases is a complex issue, and a better understanding of how climate change affects exposure to fungal pathogens is a vitally important piece,” Head said.

Although much of her work is related to examining mathematical and statistical models to more clearly define the transmission dynamics of these diseases, she sees a direct link to the care of the individuals in the hot zones where the pathogens are most prevalent.

“I turned toward epidemiology for future study because it felt like the backbone of public health,” she said. “I hope that over time, I will expand my work to be more global again, but now I feel that this is the area where I can best contribute to the health of the public and advance scientific understanding.”

Head is proud to be at the forefront of the challenging research that will be required to safeguard the public from the dangers to human health presented by the likes of valley fever, histoplasmosis and blastomycosis.

“I’ve continued to be interested in fungal diseases because there are a lot of mysteries that remain to be solved,” she said, “and I feel positioned to help solve them.”

Read More in This Issue of Findings