Public Health Outside the Classroom

Nicholas Miller, Epidemiology Student

April 23, 2020, Community Partnership, Disaster Relief, Practice

Note: There was a temporary pause in the publishing of our blog posts as our team returned in early March to the rapidly changing nature of the Coronavirus in Michigan. We now wish to share the thoughts of students on their experiences just before the COVID-19 outbreak.

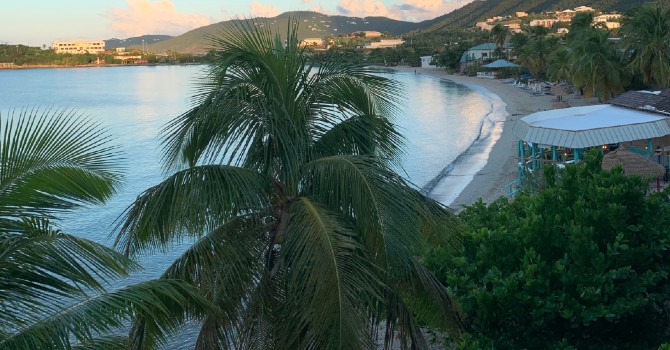

It seems that most times I get to discuss public health outside the classroom setting helps to reaffirm why I love public health. The week I spent in the Virgin Islands is no different. To hear people’s stories about the storms or other topics of concern (mosquitoes, etc.), internalize them, and then plot what actions to take that will help prevent the problems that we heard about, really puts our work in public health into perspective. During this week, the group was able to hone our public health skills, be exposed both to the interworkings of health departments (and all the problems that come with them) and a culturally different environment, all while assessing how the public health needs of a community are being met.

The opportunity to perform a CASPER in the US Virgin Islands exposed us to public health outside of the classroom. I think we talk a big game in our epidemiology classes about how to design the best study, without recognizing how these studies will play out in the real world. During our surveying, there were multiple times where we had to make decisions based on our own training in order to complete the surveys. The work that we did was dirty, it was not a controlled environment where everything worked perfectly. At times in public health we get caught up in the academic value and not the impact that the work has; sometimes we focus more on whether a work can be published in the best journals and less on the actual impact the work has. That is what I feel the CASPER we performed is all about, less on statistical significance of what we found and more on the personal significance of the data. It my hope that the Virgin Islands Department of Health can use this data to make a change for the people of the islands.

The organization we worked with, the Virgin Island Department of Health, is severely under resourced, like the majority of local public health organizations. However, they have strong capital in the people that work for them. These people were committed to helping administer the CASPER with the Michigan students. The health department, especially on St. Croix, was just as impacted by the storms as the community was. Despite the lack of resources, the health department has pushed for increased services such as lab test for lab samples. On St. Croix, all of this work was being done out of FEMA trailers as the permanent building they used to work from was severely damage during the storms. In these conditions, the health department tries its best to provide the essential services that the islanders need. Everyone freely admits that what the health department is currently doing might not be enough but they are actively working to change that.

Working in the culturally different environment of the Virgin Islands, I really found myself being deferential to our local partners, especially when it came to asking people to take our survey. I fully acknowledge that for some islanders, the prospect of discussing their problems with me did not sound appealing. Thus, I usually asked the local partners to ask “INSIDE?” and to ask people participate in our survey. However, depending on the community we were in, sometimes I would ask the survey or the local partner would; it depended on who we thought the participant was most comfortable with. Thus, we approached every interview with humility with respect to the people we were surveying.

By performing this CASPER, we were able to reach out to the community to understand which issues the community is facing. The CASPER was a clear way to assess the needs of the people. In public health, it is incredibly important to work with the community if our interventions are to be effective. It is easy to look at some surveillance data and conclude a community needs some program but that might not be what the community actually views as the most important problem. Furthermore, there are certain problems that may not be apparent without community engagement. Thus, the use of CASPERs as a way to hear from the community is a super important tool in the public health arsenal.

The week spent in the Virgin Island was an immeasurable learning experience as a public health professional. We were exposed to new techniques, organizations, and most of all, people that further educated us on how public health occurs in the real world. Our time (and thus, degrees) are designed to prepared us for public health practice out in the real world; experiences such as the work we did in the Virgin Islands prep us for public health outside of academia in a way that we do not receive in the classroom. Performing the CASPER in the Virgin Islands was a super important experience in making me a more well-rounded public health professional.