Interview with a Pathogen: The Importance of Investigative Reporting in All Things

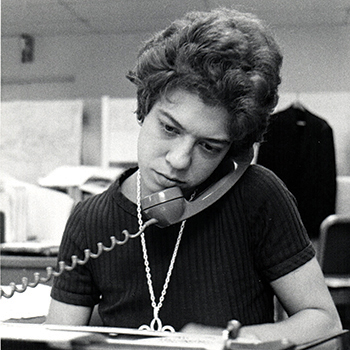

Dolly Katz, MPH ’90, PhD ’95

Senior Epidemiologist, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Our sixth-grade teacher, Mrs. Method, decided our class was going to produce a newspaper.

She got a mimeograph machine and gave out our assignments. I wrote up our recent trip to the art museum. As she paced up and down our rows of desks reviewing the stories, she was quite the tough editor. While looking over my shoulder to read the museum story, she suddenly slapped my desk and proclaimed, “Now this I can use!”

From then on, I planned on being a reporter. When I arrived at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I got a job with The Daily Cardinal. After college, I worked as a reporter, first for the American Hospital Association in Chicago, writing news stories for their main journal, then for a small paper, The State-Journal Register, in Springfield, Illinois.

That positioned me well for the job I would have for years to come—as a medical reporter for the Detroit Free Press. That paper had a broad concept of what a medical reporter could cover, so I wrote on all kinds of things, from Detroit’s abortion scene to the latest pharmaceutical breakthrough.

But what always interested me the most was epidemiology. Back then, a reporter could call the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and within a minute or so be on the phone with an expert, a trained scientist working for the federal government. It was always amazing to me how they knew what they knew. How did they know it was the potato salad and not the macaroni salad, and how did they figure that out?

I made a promise to myself: If ever the newspaper business becomes a problem for me, I will become an epidemiologist.

During my years with the Free Press, the chief epidemiologist at the Wayne County Health Department became a sort of science mentor to me. I called him all the time, whenever I needed a voice of truth in a big medical story. He would always tell it straight, and I would always learn a lot about science and what it takes to get scientific truths out to the public. I called him during the 1976 swine flu outbreak and he gave me a very straight answer about the evidence at hand and the dangers of marketing a vaccine too quickly.

As a result of these fascinating conversations about epidemiology—and the important, complicated relationship between science and public policy—I made a promise to myself: If ever the newspaper business becomes a problem for me, I will become an epidemiologist.

About ten years later, the newspaper industry did become a problem. The Free Press and The Detroit News got into a pricing battle that resulted in their merger under a special exemption from the antitrust laws. I was ready for a change, and I began thinking more and more about how much I loved epidemiology.

The school wants a broad diversity of voices, perspectives, and talents.

I called the University of Michigan School of Public Health and was put through to the director of admissions. I told him I had a bachelor’s degree in political science and wanted to be an epidemiologist. He said, “come on down!”

This openness is why, when I die, any money that’s there is going to the School of Public Health. From that first phone call, the school was fully committed to me becoming an epidemiologist. And I was by no means the only student who had what you might call an “unusual trajectory.” The school was and is open to people from any profession and from different walks of life pursuing paths to public health together. The school wants a broad diversity of voices, perspectives, and talents.

Because of the school’s commitment to me, and with my advisor’s encouragement, I stayed at Michigan for a doctoral degree after I finished my master’s. While working on my master’s degree, I had worked for the Michigan Department of Public Health. After completing my PhD, I became an Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officer at the CDC, a two-year fellowship program and something of a dream job. From there I worked as a regional epidemiologist in the Florida Department of Health for nearly six years before returning to the CDC to work as an epidemiologist in the Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, where I am now.

My journey is not all that unusual. The field of journalism generates a lot of engagement with other professions and has been for many a pathway to many professions.

With my journalism background, I was well-equipped to become an epidemiologist. Journalists know how to ask questions. They know how to do research and how to interview people. They know how to get information out of people who don’t necessarily want to offer it. And they can think outside the box—if one approach isn’t working, try something else. Journalists do these things for a living.

For a long time, journalists have even used many formal epidemiology methods. Predicting elections by applying statistical models to polling data can get journalists pretty close to knowing who will win an election as election day approaches.

In a sense, journalists and epidemiologists do the same thing. You ask questions to find out what is going on. You write it down, make sure it’s accurate, you get it reviewed, and you publish it. Different venues, sometimes different audiences (though not always)—but the same basic methods.

Importantly, journalists and epidemiologists both need to know how to write. The simple declarative sentence remains the foundation of good journalistic writing and is extremely important when writing scientific manuscripts as well. Mrs. Method’s sixth grade assignment was still with me, propelling me forward in my new career.

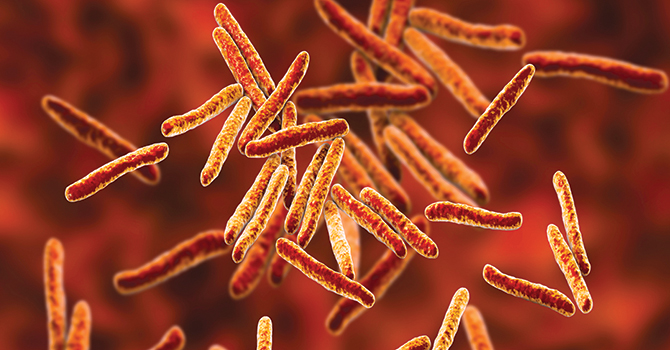

Today, I help to run a consortium of academic institutions and health departments partnering with the CDC to improve testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection—a condition in which the tuberculosis infection persists but the immune system controls it so that a person is not symptomatic, ill, nor contagious. Some events that affect the immune system—through aging or disease—might reactivate the pathogen and can cause the disease known as tuberculosis.

Most people who have a latent tuberculosis infection live normal lifespans, die of other causes, and never know they are infected. But the relatively small proportion of people who go on to develop TB disease and transmit the infection to others made tuberculosis the leading cause of death in the US at the end of the nineteenth century. Today, although tuberculosis is under control in the US and other developed countries (about 9,000 cases in the US in 2018, with around 500 deaths a year), it remains one of the top-ten causes of death worldwide and the leading cause of death from infectious diseases. The World Health Organization estimates that each year 1.8 billion people—close to one quarter of the world’s population—have latent tuberculosis infection, 10 million go on to develop tuberculosis, and 1.5 million die of the disease.

With so much interaction between humans and this pathogen, it is important to continue interrogating tuberculosis.

Part of my fascination with this complex disease is its huge impact on human culture. Tuberculosis has been around for at least 9,000 years and is still changing and evolving with humans. It has had a massive impact on science, public health, and medicine. Many works of art—operas, books, paintings—are about tuberculosis, which for centuries we called “consumption” because the disease seemed literally to consume its victims, whose weight dropped drastically as the disease progressed. With so much interaction between humans and this pathogen, it is important to continue interrogating tuberculosis. Thankfully, I work on a dedicated team of scientists here at the CDC who know how to ask the right questions and write a good declarative sentence.

My journey is not all that unusual. The field of journalism generates a lot of engagement with other professions and has been for many a pathway to many professions. Whether I’m interviewing a health worker for a story or a pathogen for a study, I have to ask the right questions, get good answers, and translate those answers into information that informs the public. It doesn’t really matter who your employer is—investigative reporting will always be a vital part of the human search for truth and health.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more about Michigan Public Health alumni around the country and world.

- Support research at Michigan Public Health.