Three Generations, One Passion: When Public Health Runs in the Family

By Laura López González

Every day like clockwork, Michelle Khurana piled into the backseat of her parents’ car for the trip west from Plymouth, Michigan, down Ann Arbor Trail toward the city. It was the 1970s, and at the wheel sat the toddler’s father—an Indian-trained doctor, newly arrived in the country by way of the United Kingdom and just beginning to establish an internal medicine practice.

Eventually, the car would turn onto Observatory Street, arriving at a parking lot near Washington Heights.

And then they waited.

Michelle’s mother, Dr. Zubeida Khurana, had landed in the US with a busy toddler and another baby on the way. Still, a friend had convinced her to enroll in a master’s program at the School of Public Health.

So for two years, Michelle and her father made the daily trip to campus, waiting for Zubeida to emerge after class.

Almost 20 years later, Michelle would find herself in the same parking lot. This time, she was the student.

“It is surreal,” says Michelle, who graduated from the School of Public Health in 1996 before going on to become a medical doctor. She adds with a laugh, “It is doubly surreal when my daughter is there and I’ve dropped her off and picked her up from the same spot on campus.”

A Family Tradition Half a Century in the Making

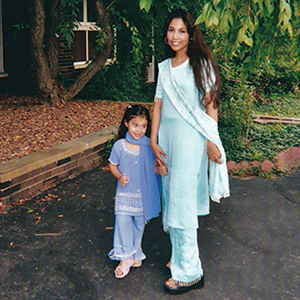

Today, Michelle’s daughter, Laila Odeh, is completing a bachelor’s degree in public health—making her the third generation of the Khurana family to graduate from the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health. Laila is carrying on a family tradition of community service and following in her grandmother’s footsteps with a bit of help from her mom—and some talents Michelle says run in the family.

Zubeida says she was drawn to medicine from an early age in India, creating her own concoctions to treat friends’ scrapes and bruises. By the time she was 12, she was helping out at a cousin’s private gynecology practice, where she scolded the cousin for shouting at the women filing through the door.

“I’d say to her, ‘Talk softly to the patients,’” Zubeida remembers.

“I used to spend so much time with patients getting to know them. I knew each patient

and their family . . . all their background.”

—Zubeida Khurana, MPH '76

As a child, Zubeida realized that talking was as much a part of any cure as medicine. As a doctor, it defined her career.

“I used to spend so much time with patients getting to know them,” says Zubeida of her days in private practice, during which she also worked evenings providing sexual and reproductive healthcare at Planned Parenthood. “I knew each patient and their family . . . all their background.”

Zubeida laughs, “When I was retiring, oh my God—there were all these crying spells. But sometimes, we’d be out somewhere, like in the mall, and people would come up from behind and just hug me.”

“I turn around and there are my patients,” she says. “They’re more like my friends.”

She spent so much time talking with patients that, as a child, Michelle wondered if her mother really practiced any medicine at all.

“In public health, we have to look at the patient holistically.”

—Michelle Khurana, BS ’93, MPH ’96

“I remember when I was little thinking that she’s not even doing medicine—she’s just talking,” says Michelle, who spent hours as a child at her parents’ practice. “But when I became a physician, a parent, an adult—I realized that’s what public health is. It’s not just medication or vital signs, it’s what’s going on in your home. Are you worried about your job or finances? Do you have money for medication? Do you have time to exercise?”

“In public health, we have to look at the patient holistically,” Michelle says.

A Mother Knows Best

Despite coming from a family of doctors, Laila had no intention of pursuing a career in health when she started at the University of Michigan. Instead, she toyed with the idea of majoring in political science or public policy. Laila was unconvinced when her mother suggested she sign up for the Public Health 200 course.

“I remember her actually showing me a Findings magazine and saying, ‘This is the kind of stuff you like,’” Laila recalls. “I thought, ‘no, it’s definitely not.’ I didn’t give it a chance.”

“Then I opened it,” she says, sighing. “And she was right.”

But within weeks, Michelle received what she thought was a panicked call from the reluctant public health student. Thinking it was an emergency, Michelle stepped out of a meeting.

“Oh my God, Mom,” Michelle remembers Laila saying on the other end of the phone. “Did you know that African American women have the highest maternal mortality rates in the country?”

Michelle knew then that Laila had found her place in public health.

“I knew, personality-wise, she would like it and find it interesting,” Michelle says, “With health inequalities? Laila gets super passionate about it—she just can’t stand it.”

Laila says she’s been inspired by faculty such as Riana Elyse Anderson, assistant professor of Health Behavior and Health Education. Anderson’s groundbreaking work on racial discrimination, trauma, and healing among Black families has made her a frequent voice in news outlets such as the New York Times, CNN, and Psychology Today.

My grandmother treated her patients’ ailments, but more than that, she was a person

for them to talk to. She had so much empathy for her patients, and that’s something

that inspires me now.”

-Laila Odeh, Bachelor’s Student in Public Health

Like Anderson, Laila is hoping to work on racial equity within healthcare. As a first-generation Indian-Palestinian American, Laila has a particular interest in working with immigrant and refugee communities, following in her grandmother’s footsteps. Zubeida provided medical services at Dearborn’s Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS) and also served as a board member.

“Many refugees and immigrants attend my mosque, and they’re the kindest people. But they have to deal with a lot of stigma,” she says. “In general, there’s a huge gap in culturally-aware health services for this population.”

Laila is currently applying to graduate school, where she plans to study public health and social work.

“My grandmother treated her patients’ ailments, but more than that, she was a person for them to talk to,” Laila says. “She had so much empathy for her patients, and that’s something that inspires me now.”

About the Author

Laura López González is a freelance health journalist and editor. Her work has appeared in outlets such as Al Jazeera, the Guardian, and Devex. Follow her on Twitter @LLopezGonzalez.

Photography by Scott C. Soderberg

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read “Humanity Rises: The Personal and Professional Lives of Two Scientists Combating COVID in India”

- Support research and engaged learning at Michigan Public Health.