Humanity Rises: The Personal and Professional Lives of Two Scientists Combating COVID in India

By Fernanda Pires

As COVID-19 arrived in their home country of India over a year ago and created a devastating wave of disease this spring, Michigan Public Health biostatisticians Bhramar Mukherjee and Mousumi Banerjee have stepped into new roles as go-to experts and advocates—offering their advice to heads of state, appearing on international news shows, and organizing charitable giving.

What is it like to be taking on these new and augmented roles?

“I have definitely been thinking differently over the past 18 months,” says Mukherjee, John D. Kalbfleisch Collegiate Professor and Chair of Biostatistics. “I am focusing on evaluating and promoting public health interventions that address problems directly and save lives. This is different from my past work concentrating on association studies and quantifying evidence. I want to influence policy and the data ecosystem in India through data-driven research.”

“I believe in humanist values,” says Banerjee, Anant M. Kshirsagar Collegiate Research Professor of Biostatistics. “Whether in my professional work, my passion for the arts, or bringing up my children—above all else, I try to live in a way that prioritizes people.”

Their engagement in data science and desire to serve their communities brought Mukherjee and Banerjee together when the pandemic first struck. They wanted to understand what was happening in India—still home to most of their family members.

Three Days to Publish a Model

In January 2020, Mukherjee became intrigued by the work of fellow Michigan Public Health biostatistics professor Peter Song, who had built an epidemiological model for the Wuhan data. “At the time, the pandemic wasn’t so scary—it was more of an academic interest,” she said.

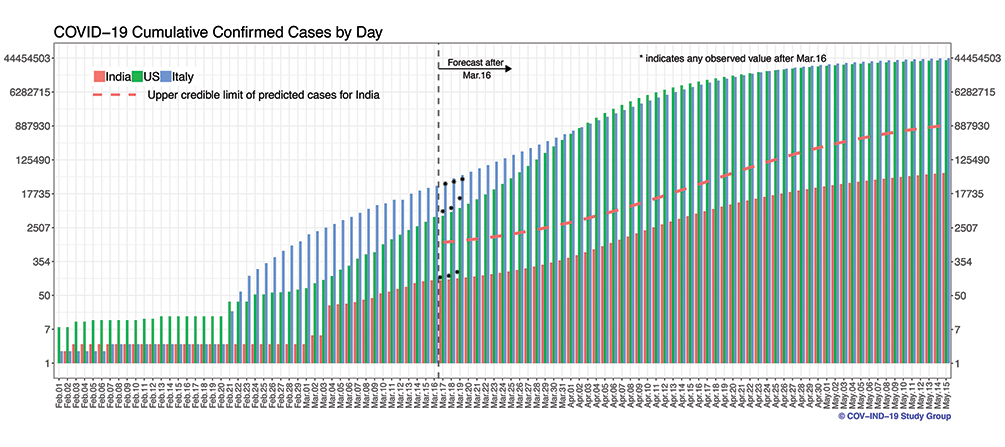

In March, India had reported only 536 cases and 11 deaths. But, Mukherjee notes, by following the virus’s path in the US and Italy, you could see what was about to happen. “We have many students and faculty of Indian origin in the Biostatistics department, and we were all anxious,” she remembers. “I called everybody and said, ‘I really need your help. Drop everything, we have to raise awareness through our projections. I think this will make a difference for all of us.’”

We can work together, unite our knowledge, and provide vital scientific information.

This can be our contribution as public health data scientists and citizens.

—Bhramar Mukherjee

Instead of agonizing, they invested. “Let’s take a deep dive into the problem,” Mukherjee told her colleagues. “We can’t go to India right now. We are not able to help on the ground. But we can work together, unite our knowledge, and provide vital scientific information. This can be our contribution as public health data scientists and citizens.”

In their collective effort, a modeling initiative related to COVID-19 was born.

“We were all feeling concerned about the situation in India and worried sick about our families,” Banerjee said. “After Bhramar’s call, we worked nonstop day and night to get our first article out. Three days later, on March 21, 2020, our first prediction model for case counts and projections in India was published.”

The scientists didn’t anticipate that the Indian international media and dozens of other news outlets would pick up and report on their research.

“The next morning, our pictures were everywhere saying that our study had predicted that a difficult future was coming for India,” Mukherjee says. “Just days later, on March 24, 2020, the historic lockdown in India was announced. Seeing our work have such an immediate and broad impact was something quite spectacular.”

Advocating for Transparency

In the following weeks, Mukherjee, Banerjee, and their team were obsessed with analyzing data from India and its population of 1.34 billion. They knew that data-driven modeling could inform and guide policymakers and stakeholders to address the global pandemic as it struck their motherland.

“I was closely following the data emerging from my home state of West Bengal. It became apparent that there was data falsification in our state. They were underreporting not only case numbers but also deaths,” Banerjee said. “There was an absolute lack of transparency. Often, COVID-19 fatalities were recorded as related to various other causes, like underlying conditions or organ failure.”

You might live on the other side of the world from India, but this is not India’s

problem alone. Pandemics are everyone’s problem. Big or small, we all must do our

part.

—Mousumi Banerjee

Together with a group of 14 health scientists, physicians, and providers all raised and educated in the state of West Bengal but not currently living there, Banerjee wrote an open letter addressing their concerns on the gross under-testing in West Bengal and the misreporting of data on the causes of COVID-19 deaths.

“It was my first brush with activism,” Banerjee said. “We are spread all around the globe. But even beyond our common ancestral heritage, we are linked by our public health conscience during this time of unprecedented global health disaster.”

Political arguments, public protests, government pressure, email threats, messages of support, national television interviews and debates—their letter provoked mixed responses from government officials and local communities. A few weeks later, another coalition—this time 75 public figures in West Bengal, including writers, filmmakers, actors, musicians, and academics—showed their support and also asked state officials to “rise above petty whataboutery and listen to experts in dealing with the health crisis.”

“When politics interferes with human lives, I cannot stay quiet,” Banerjee said. “In the end, the government sent another independent committee to evaluate the reporting of data in the state and they came out with similar observations as ours. It doesn’t mean the numbers are totally accurate now, there are still questions and challenges. But it is no longer a joke. They know everyone is watching now.”

Their research and predictions have kept Mukherjee and Banerjee in the media spotlight for months.

“This year, I was on television more than my father, who is a well-known actor in Kolkata,” said Mukherjee laughing. “I am very excited to talk about public health, from personal insights to population statistics. The impact of this work on my life as a scholar and educator has been profound. I get so many emails every morning. I wake up to emails from students in India saying, ‘I want to study biostatistics because of your work.’”

“That’s perhaps the biggest impact—a young woman sitting in a village in India thinking about becoming a biostatistician because she saw you talking about what this profession can do and being fearless about speaking the scientific truth.”

Risking Travel during a Pandemic

Mukherjee and Banerjee also felt the urge to go home, to be close to their families. Mukherjee went first—in November.

“Being an immigrant scientist from India, I have always celebrated my hyphenated identity, shuttling back and forth between the two continents each year,” Mukherjee says. “This was the first time in 24 years that I had to live in agony from not being able to visit my parents.”

Her travel was model-informed. She looked at the data and “knew that November to January would be the valley of the curve,” she notes. There were many concerns, of course, including not yet being vaccinated at the time.

While preparing for travel, she talked to epidemiologist colleagues, read papers and news articles, and designed a very personal risk management and mitigation strategy. But Mukherjee decided to go because her family—especially her parents, who are in their 80s—was “becoming fatalistic. They thought they might never be able to see me again.”

“I took every precaution, designing my journey in a very careful way,” Mukherjee said. “I wore a hazmat suit, N95 mask, goggles, face shield, and gloves. I looked like an astronaut but was totally okay with that. It is better to be safe than fashionable.”

Once in Kolkata, Mukherjee stayed in her apartment to quarantine before seeing her elderly parents. “This trip was a tribute to my parents and to public health prevention strategies,” she says. “I had been looking at their photos on my desk for too long. I had to see them.”

Banerjee’s journey to Kolkata in March 2021 had similar planning, safety protocols, and protective gear, including the astronaut outfit. Her mission: to get her 84-year-old mother, who suffers from multiple comorbidities, vaccinated.

Three days after she arrived in Kolkata and was still in isolation, her mother received her first dose with no adverse reactions. Her plan was off to a good start.

It didn’t last long. With quarantine complete, Banerjee was able to escort her mother for her second vaccine dose after four weeks. With registration and appointment confirmed, they made their way to the fourth floor of a vaccination center.

“When I got there and saw a small, overcrowded room—about 75 people in one space—my heart started racing,” she said. “My public health conscience was yelling to get out of there. But I couldn’t. My mom needed to be vaccinated.”

After a long wait, the center announced it had run out of vaccines.

“I panicked. Everyone panicked. I could not believe it,” Banerjee said. “After phone calls, more waiting, and lots of anxiety, my mom got vaccinated. It was a very stressful situation.”

More stress was still to come.

As cases in India were skyrocketing and the US announced it would close borders to travelers from India, Banerjee was planning her journey back to Michigan.

On her to-do list was a mandatory COVID test, which came back positive.

“I was shocked by the result—crushed,” she said. “I’m an informed public health scientist. It’s my job. I had taken all public health precautions. When the result came back positive, I just broke down. For 24 hours, I lost my ability to think. As a data scientist, I deal with uncertainty all the time. But I couldn’t handle this uncertainty in my own life, not to mention the disaster still unfolding across India.”

Banerjee canceled her flight to the US, not knowing when she would leave India. She self-isolated for a week, then took three tests with three different labs. “All three came back negative,” she reports. “The emotional wreckage from the earlier false positive was huge. But I felt loved, cared for, and nurtured by friends and family in India during quarantine.”

On May 1, 2021, eight days after the false positive, she was flying out of Delhi.

“On the plane, I cried for a long time,” she said. “I left the city with a strange set of emotions. I knew it was time to leave, my job there was done. I needed to return here and leverage my position to help my country.”

Supporting from Afar

When friends, family, students, and colleagues learned of Banerjee’s journey, they wanted to support her West Bengal community. With no time to waste and clear goals, she started a fundraising campaign through Tagore Beyond Boundaries—an arts and humanitarian foundation Banerjee created in 2014—to mobilize dozens of people.

“We decided to assist health centers in Kolkata. I had been there and had witnessed the need,” she said. “With my connections in the area, I could communicate directly with local providers delivering care. Each week, we knew exactly what they lacked.”

To support regional businesses and avoid shipping costs, they bought locally. Banerjee’s foundation helped provide oxygen supplies, masks, surgical gowns, and oximeters to local health centers and food to small villages in the suburbs of Kolkata.

“If everyone takes small steps to help their own community, we can alleviate a lot of pain,” Banerjee said. “We now need increased vaccination and other preparations for future outbreaks. We also need economic recovery in the countries most affected by COVID-19, like my own.”

While Banerjee raised funds to deliver supplies, Mukherjee and her team—which now includes 15 graduate students—continued to analyze epidemiologic data to make predictions and recommendations for India’s devastating second wave. Mukherjee’s own family was ravaged by the second wave, with her father, sister, and nephew all being hospitalized with COVID.

At times like these humanity rises. It has to.

—Mousumi Banerjee

Mukherjee hopes a robust vaccination program can keep another wave at bay. “India has a very young population, with 40% of people age 18 or younger. They cannot be vaccinated right now as there are no vaccines approved in India for this age group,” Mukherjee said. “India is unlikely to reach herd immunity without a vaccine for the young, so the importance of public health interventions is further amplified. It will be critical for India to vaccinate as many as possible, as fast as possible, while also tracking new variants.”

With the global pandemic far from over, these two immigrant scientists continue raising their voices, their science, and—they hope—more of humanity.

“At times like these humanity rises. It has to,” says Banerjee. “You might live on the other side of the world from India, but this is not India’s problem alone. Pandemics are everyone’s problem. Big or small, we all must do our part.”

About The Author

Fernanda Pires is a senior public relations representative at Michigan News. She holds a master’s degree in journalism and broadcasting from Michigan State University and worked as a reporter and newswriter in Brazil.

- VIRTUAL EVENT - MARCH 10, 2022 at 4:00 PM - COVID in India Two Years Later - The Personal and Professional Lives of Two Public Health Scientists Battling the Pandemic featuring featuring Dr. Bhramar Mukherjee and Dr. Mousumi Banerjee in conversation with Dean DuBois Bowman. Learn more here.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read “Three Generations, One Passion: When Public Health Runs in the Family”

- Support research and engaged learning at Michigan Public Health.