A daughter’s promise

Doctoral candidate Sara Feldman is shaping field of dementia research

By Laura López González

American society is at a crossroads. The number of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in the United States is projected to double by 2050. Meanwhile, the country is growing older, and within roughly 10 years, the US Census Bureau predicts that the elderly will outnumber the young for the first time in American history.

For University of Michigan School of Public Health doctoral student Sara Feldman, dementia isn’t just something she studies, it’s something she lives as a full-time caregiver. Today, she’s working to give future families living with dementia one of the greatest gifts of all: choice.

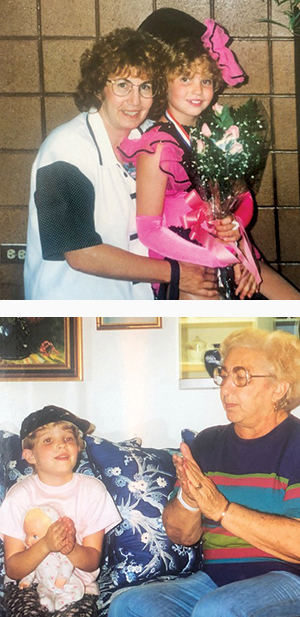

The pair were getting ready to see Barbara’s parents—retirees who had traded the harsh Brooklyn winters for Florida’s perpetual summer. Sara and her mother visited from their home in Colorado every chance they could.

“She might not remember you,” Barbara said gently to her young daughter, Sara. Nearby, a set of suitcases stood packed.

But Sara’s grandmother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, a form of dementia, shortly after Sara was born. In people who have the disease, the brain begins to shrink and brain cells die, leading to a decline in thinking, physical, and even social skills that can limit a person's ability to live independently. Although some medications may help slow or temporarily improve symptoms, there is no cure for the disease.

So, each vacation south came with Barbara’s tender warnings to her little girl.

“You know,” Barbara would say, “she might not remember your name.”

“It was my mom preparing me for what I might see because dementia—and, specifically, Alzheimer's disease—is progressive,” said Sara, now an adult. “We didn’t know what we were walking into every time.”

Still, as a young child, Sara wasn’t worried.

“I was more focused on playing with her, and she was really good at playing,” she said. “But as I got older, I realized my grandmother couldn’t follow through on things. She couldn’t drive, eat, or shower on her own. She wandered and frequently became lost and, over time, lost the ability to communicate and respond to stimuli.

“When she transitioned to a nursing facility, it became very evident that she was sick in some way, even at my young age.”

Parts of the woman who Sara remembers for her big belly laugh and a love of makeup began to slip away. The trips to Florida got harder.

“As sad as it was,” Sara said, “it made me really joyful to be with her because I loved spending time with my grandmother even when she couldn’t recognize me.”

Just barely a teenager, Sara had come to understand that the specter of dementia had haunted her family for two generations.

When she was 13, Sara Feldman turned to her mother, Barbara, and made a promise.

“If you’re ever in a situation like grandma,” Sara told her mother, “I don’t want you in an institution. I want you at home, and I’m going to do everything possible to make that happen.”

Diagnosis cuts deep

Sara spent much of her 20s working on disability and health education and inclusion issues, first as an educator and then caseworker in Colorado, and then as far afield as Senegal, Tanzania, and India.

“I wanted to contribute to and engage with communities but also grow personally and professionally,” Sara said of her time abroad. “Still, I realized within my work that I constantly hit this metaphorical wall in being able to do what I really wanted to do with the degree I had.”

When Sara returned to the United States to pursue a Master of Public Health (MPH), the University of Michigan was a natural fit.

“I wanted a reputable public health program, which, of course, Michigan had,” Sara said. “But I‘m also interested in the social justice component of the work that I do by expanding opportunities for inclusion and equity, and that seemed to be a strong focus within the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education.”

But four months into her MPH program in 2016, Sara received an email from a family friend in Colorado with whom Barbara had been living.

“I hate to do this, and I love your mom and our friendship,” the email read, “but I’m being more of a caregiver for her than a friend. I can’t be that person.”

Sara had a little over a week to move her mother across country, from Colorado to Ann Arbor.

“I entered the second year of my master's program grieving, worried, and in crisis mode,” she said. “In addition to acknowledging that I was losing more of my mother each day, I was also forced to evaluate how to be a full-time student who was also employed while also being a caregiver.

“And I was navigating the shifting roles of our mother-daughter relationship.”

Barbara was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer's dementia within six months after moving to Michigan to live with Sara.

Sara had expected the diagnosis given her family history and because of Barbara’s increasing propensity, for example, to forget conversations, or to pay bills or close doors and even the occasional bowl of soup that found its way into a sock drawer.

“I remember one of my very first conversations with my mom's primary care provider years before she was diagnosed with Alzheimer's, but while she already had mild cognitive impairment,” said Sara, who came to the appointment armed with a list of concerns about her mother’s health that she had hoped to discuss with the doctor.

“He said I might be overthinking some of the concerns I had over my mother and just shrugged them off,” Sara said. “Because we can’t prevent or treat dementia—and because she didn’t have all the more advanced dementia symptoms—the doctor was just sort of like, ‘It’s not time to have this conversation.’

“It was dismissive. I would have really valued having those conversations about even her risk of dementia much earlier on, particularly given family history and her diagnosis of having mild cognitive impairment.”

Still, Barbara’s eventual Alzheimer’s diagnosis cut deep: “It was like a thousand punches.

“I was a full-time graduate student also working part-time in a state that I’d never lived in before. I didn't know anyone. I didn’t have a community. I thought, ‘Well, now what?’”

Is DNA testing for everyone?

If a simple test could tell you whether you were at risk of an incurable disease 20 years from now, would you take it?

Scott Roberts’ wife would not.

“She thinks it would just stress her out,” said Roberts, professor in the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education at the University of Michigan.

Still, Roberts has spent much of his career working to answer that question regarding Alzheimer's disease.

Roberts was training as a clinical psychologist at Duke University when researchers there discovered the link between a gene called apolipoprotein E (APOE) and Alzheimer's risk in the 1990s.

Although one form of the gene is linked with a reduced risk of the disease, another more common type of the gene, APOE e4, can be associated with an increased chance of developing Alzheimer’s. Still, it’s a risk factor, not a given that someone with this version of APOE will have Alzheimer's one day.

Should this kind of genetic screening even be available to patients, the medical community began to wonder?

If it were available, would the results spark terrible depressions, some doctors worried? Or could patients use it to plan for their future—maybe take out better insurance or retire early to make the most of their time before they might get sick?

By 1999, Roberts had joined scientists from the University of Michigan and other institutions to work on the REVEAL study to find out. Ultimately, he said, more than 10 years of research showed no major risks for patients.

“If people do get bad news, they may have some initial distress, but they tend to get back to their baseline levels of depression and anxiety relatively quickly,” said Roberts, who pointed to several caveats. For one, trained counselors disclose a person’s genetic risk for Alzheimer's, unlike popular mail-order DNA testing services that provide similar information directly to the public without follow-up.

‘You don’t have to do this alone’

Sara began to consider shifting her career focus from disability generally to dementia while still in her MPH program, around the time of her mother’s diagnosis. Colleagues in the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education quickly referred her to Roberts.

Given his experience, Roberts knew Sara, like all caregivers, couldn’t do it alone. He also sensed that reaching out for support might not come naturally to fiercely independent Sara.

I just kept trying to say: You don’t have to do this alone even though you are super-capable--there are resources out there.

-Scott Roberts

“I think that resonated with her and made her more open to the idea of asking for help as opposed to trying to figure these things out on her own.”

Sara credited Roberts for helping her navigate her mother’s transition to a newly defined life—and the reimagining of her own future, helping her harness her passion for dementia into a research career that is at once fulfilling and allows her to provide the 24-hour care that her mother needs.

“He was the person who connected me to the health care system, to different health care providers, and the Alzheimer's Association,” she said. “He has been by my side through thick and thin, good and bad, and throughout both my MPH and now my PhD career.

“I've learned from him, and I learned with him. I’m blessed to be able to work with him.”

Round-the-clock responsibility

With Roberts’ help in navigating resources and getting connected to local services and organizations, Sara enrolled Barbara in the Silver Club Program at the University’s Turner Senior Center. The program organizes activities for adults living with dementia, such as art and fitness classes, and provides a chance to socialize.

The Silver Club, and programs like it, also provides caregivers like Sara some time off, which she needs, said Elyse Thulin, a close friend and fellow doctoral student in the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education.

“Sara is awake into the late hours and is also up pretty early in the morning to try to get some work done before anyone else in the house is awake, which includes Barbara and her dog,” Thulin said of Sara’s beagle mix, Simba. “But when Barb’s awake, Sara is generally spending time with her, both to keep her engaged and also because her mom cannot initiate tasks or entertain herself beyond playing games on her iPad.”

For Sara, caregiving is a round-the-clock responsibility that involves thinking ahead to ensure her mother’s well-being—from writing and calling Barbara’s friends now that her mother can’t do this herself, cooking and cleaning, and even hiding household chemicals and medicines to prevent accidents.

And it’s about doing the little things her mom loves too. The pair eventually traded their Ann Arbor apartment for a home in Ypsilanti that could accommodate a paid live-in caregiver for Barbara if she ever needed one. There, Sara planted a huge vegetable patch. In the summer, a sign marked “Barbara’s Garden” hangs near rows of peppers and tomatoes, including the tiny burst tomatoes, the main ingredient to one of Barbara’s favorite pastas, which Sara often cooks her.

“Sara and Barbara are crazy about tomatoes,” Thulin said.

Regulars and baristas at RoosRoast Coffee Shop in Ann Arbor know the mother and daughter duo by name.

“Her mom really enjoys going out for coffee, and so that’s something that Sara would build into their schedule—taking an hour or two to go to RoosRoast, have a coffee, look around, and chat with other coffee-goers,” Thulin said.

And when COVID-19 kept the pair out of their usual coffee haunts, Sara purchased espresso and milk steamers, and perfected how to make her mother’s morning latte at home.

“But that’s Sara,” Thulin said. “She just has this truly unique way of being with people and not just her mom. I can’t really explain it beyond just that she creates space for you to be whoever you are.

“You just really feel seen when you’re with her, and I think that’s part of why she’s so good at creating community—it’s her superpower—and not just for herself, but for her mom.”

Recently, Sara faced some unexpected health problems. Soon, neighbors, friends, and colleagues began showing up like clockwork to provide support, whether that was dropping off cooked meals as part of a meal train, delivering groceries, or even shoveling the driveway after winter snows. One neighbor, Nick, even volunteered to accompany Barbara on a flight to Colorado so Sara could have time focused on her health and surgeries while also allowing Barbara to stay with and visit friends.

“I’m not even sure Nick had ever been on a plane, but he did that to support Sara,” Thulin said. “Sara doesn’t like to ask for things, but I think she gives so much care and space to other people that when you feel like you can do something for her, you’re like, ‘Yes, please, let me help.’”

A ‘family affair’

Today, Sara has been keeping the promise she made to her mother as a child for the past six years as her full-time caregiver. She’s also found her voice as a caregiver and advocate, increasingly speaking about her experience, including in academic journals.

But Sara is also using her experience as a full-time caregiver to help shape groundbreaking research on dementia at Michigan Public Health, including studies investigating how people react to the news that their brains bear biomarkers, or physical signs, strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease and a possible Alzheimer's dementia diagnosis in the future.

Today, because of Sara’s experience and advocacy, studies like these are—for the first time—capturing what early access to this kind of information means for future family caregivers.

“In a lot of our studies, our data has only been collected from the person who is getting tested,” Roberts said. “Sara feels like even if people in our studies aren’t symptomatic, they’re still often talking about dementia with loved ones—it’s a kind of family affair.

Sara feels people should have the right to decide for themselves whether that information might be useful.

-Scott Roberts

Tears began to well up behind Roberts’ thick-rimmed glasses.

“She’s just been such a great research team member, and she’s just such a wonderful person,” he said.

If you had asked Sara 10 years ago if she would attempt to earn a doctoral degree, she probably would have laughed. Today, it’s changed her life and will potentially help change the lives of millions of future families that will have to confront dementia in the coming decades.

“Doing a PhD has turned out to be a beautiful part of my life—it changed my career path and, 100%, I did that for my mother,” Sara said. “And I would do it again hands down.”