Understanding Black Distrust of Medicine

Joel D. Howell

Elizabeth Farrand Professor of the History of Medicine

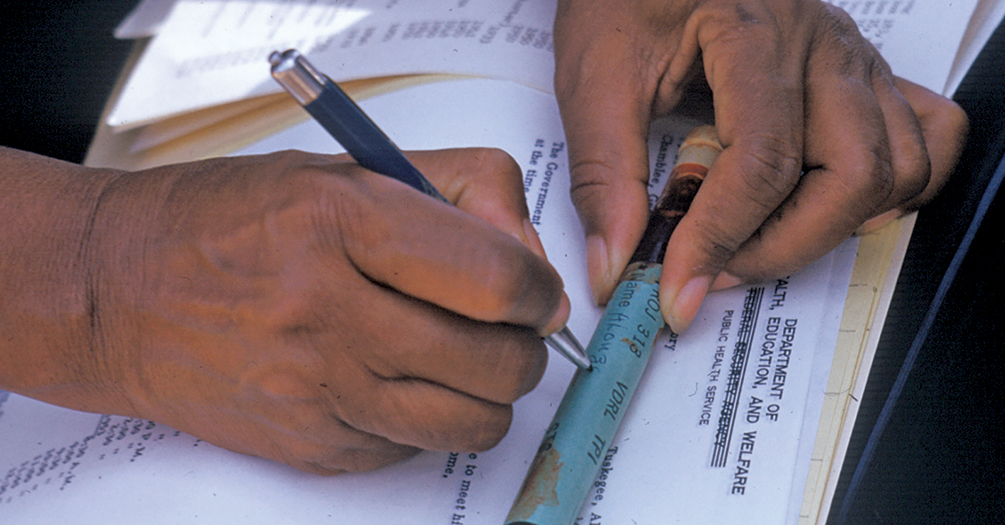

Photo. A nurse writes on a vial of blood taken from a man who was included in the Tuskegee syphilis study in Alabama, circa 1950.

Looking back on the year since the COVID-19 pandemic first struck Michigan, we can be glad the availability of safe and effective vaccines appears poised to play a major role in bringing the pandemic under control, if not completely to an end.

Yet the vaccine is of no use unless people take it. And hesitancy to take the vaccine could be a major impediment to widespread immunity, especially among some groups of people who stand a greater risk from the disease.

One of the most visible ways racism was made manifest was in multiple instances of physicians carrying out unethical experiments using African Americans.

—Joel D. Howell

African Americans’ hesitancy to take the vaccine comes in part from an awareness of the medical system’s long-standing structural racism. One of the most visible ways racism was made manifest was in multiple instances of physicians carrying out unethical experiments using African Americans. Two of the most well-known examples of such experimentation are the infamous experiments done by J. Marion Sims and the experiments done in and around Tuskegee, Alabama.

J. Marion Sims was a South Carolina physician who moved to Alabama in 1835. A few years after he arrived, Sims carried out a series of experiments attempting to discover a cure for vesico-vaginal fistula, a condition usually resulting from complications of childbirth and causing women to leak urine and stool uncontrollably.

Sims set out to find a cure for this condition by operating on enslaved women. At least ten women were either purchased by Sims or given to him by their owners. They lived in a hospital he built behind his house. We know the names of only three: Lucy, Betsey, and Anarcha. One motivation to find a cure was simply economic—if the fistulae from which these women suffered were repaired, they would have much more value for their owners.

As enslaved human beings, the women were not in a position to give their consent for these procedures, which could be excruciatingly painful. Sims operated on the women multiple times. Anarcha was operated on thirty times between 1846 and 1849 before Sims was successful. Although other surgeons may have actually discovered a cure first, it is Sims who has been given credit for the key findings that made closure of a vesico-vaginal fistula possible.

Sims went on to a successful career marked by numerous honors in the US and abroad and has often been called “the father of American gynecology.” He was also the first US physician to have a statue erected in his honor, on the edge of Central Park in New York City. As we became more aware of the egregious nature of Sims’ experiments in recent years, the statue was taken down (in 2018). People have proposed a new set of statues be erected to commemorate the memory of Lucy, Betsey, Anarcha, and the other enslaved women who were used in the experiments.

Almost a century later, another series of experiments raised another set of ethical issues concerning the treatment of African Americans. A 1920s survey had shown a high incidence of syphilis in and around Tuskegee, Alabama. In 1932 the United States Public Health Service (PHS)—precursor to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—decided to conduct a “study in nature” to determine the natural history of untreated syphilis in African American men.

All health care professionals need to know about these experiments, because they can offer insight into why many people are distrustful of medical systems.

For four decades, from 1932 to 1972, the PHS systematically examined 400 men with syphilis and 200 others who served as controls. The PHS physicians lied to the men about the nature of the study and the tests they were asked to undergo. When one of the men became suspicious and sought treatment on his own, the PHS prevented him from being treated.

Though they were well aware of the serious consequences of untreated syphilis, experimenters did not stop the experiments when penicillin became a safe, easy, and effective treatment for syphilis in the mid-1940s. They did not stop the experiments when new ethical codes were promulgated nor when the Civil Rights Movement led to a nationwide soul searching about racial issues.

Meanwhile, the Tuskegee experiments were regularly described in medical journal articles widely distributed throughout the US. Yet readers of the articles did not insist that the experiments be stopped. The experiments finally ended in 1972, when a whistle-blower leaked information about the experiments to the news media. One result of the experiments was the creation of a new procedure intended to prevent future ethical improprieties, the system of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

But among the most important results of these experiments are the ways they remind us of how unjustly the medical system has treated African Americans and how this contributes to a lack of trust of the system, especially among African Americans.

All health care professionals need to know about these experiments, because they can offer insight into why many people are distrustful of medical systems. It may also help to address some of the myths that have grown up around the experiments that are often found on social media. One of those myths is that the men in the Tuskegee experiment were intentionally injected with syphilis. While untrue, it’s understandable that someone knowing the PHS systematically prevented 400 African American men from being treated for a treatable disease might believe it.

Rather than simply dismissing fears about vaccination as invalid, health care workers who know what has happened in the past may be able to address the hesitancy people may have when asked to accept medical intervention. As we do so, we must keep in mind that Sims and Tuskegee are but two manifestations of a much larger set of problems.

People who have never heard of these experiments are aware of the inequities in the medical treatment of African Americans to this day, inequities that may contribute to a lack of trust in medical systems. To put it another way, if those two experiments had never happened, the underlying racism that nurtured those experiments would still exist.

About the Author

Joel D. Howell is Elizabeth Farrand Professor of the History of Medicine and Professor in the Departments

of Internal Medicine, History, and Health Management and Policy. He received his MD

at the University of Chicago and was a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar at the

University of Pennsylvania, where he received his PhD in the History and Sociology

of Science. Howell is director of the Medical Arts Program and a Senior Associate

Director director of the University of Michigan Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars

Program. He has written widely on the use of medical technology, examining the social

and contextual factors relevant to technology's clinical application and diffusion,

analyzing why American medicine has become obsessed with the use of medical technology.

Joel D. Howell is Elizabeth Farrand Professor of the History of Medicine and Professor in the Departments

of Internal Medicine, History, and Health Management and Policy. He received his MD

at the University of Chicago and was a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar at the

University of Pennsylvania, where he received his PhD in the History and Sociology

of Science. Howell is director of the Medical Arts Program and a Senior Associate

Director director of the University of Michigan Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars

Program. He has written widely on the use of medical technology, examining the social

and contextual factors relevant to technology's clinical application and diffusion,

analyzing why American medicine has become obsessed with the use of medical technology.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read Good Science Changes: That’s a Good Thing in this issue of Findings.

- Support research and engaged learning at Michigan Public Health.