A passion for Dearborn

Michigan Public Health alumni lead with a public health perspective

By Bob Cunningham

DEARBORN, MICHIGAN—Even before Abdullah Hammoud, MPH ’12, took office as mayor, he already had begun recruiting the person who would become the city’s director of the inaugural Department of Public Health.

Hammoud’s pitch to Ali Abazeed, MPH ’17, was simple but included a mutual admiration for something close to both their hearts: their hometown.

“I need you to come back and build something from scratch,” Hammoud recalled telling his close friend about his plan for Dearborn, the second-largest city in Wayne County with a substantial Arab American population. “You’re starting with no employees but yourself. You’re going to advocate for every single dollar that you have because it’s a tough economic time, but the outcomes on the other side of this are going to be immeasurable. I think that success will be worthwhile.”

When the mayor, who took office in January 2022, reached out to Abazeed, he was quite content in his role as a public health advisor at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“He said, ‘Hey, I have this crazy idea. I want to start a public health department and I’d like you to do it,’” Abazeed said. “I loved my job in Washington. I loved the NIH—it’s a job that you don’t really leave. I didn’t take it seriously at first, but what I did commit to him was just to think about it.”

The clock was ticking.

Dearborn is home. … There’s nothing like advocating and fighting for home, and there’s no place like Dearborn—we’re a phenomenal city. It’s the greatest city in all the land and that’s why we’re here.”

— Abdullah Hammoud

“I had a six-month recruitment effort to convince him why he should depart the NIH,” said Hammoud, who, in addition to holding a Master of Public Health in Epidemiology from the School of Public Health, has a Bachelor of Science in Biology from the University of Michigan-Dearborn and an MBA from the Ross School of Business. He served as a state representative in the Michigan House of Representatives from 2017 to 2021. “I had to persuade him to leave a dream job, but I undoubtedly knew he was going to continue to do great things here in Dearborn.”

Hammoud won over Abazeed by focusing on his passion for their city. In April 2022, Abazeed became the founding director of the Dearborn Department of Public Health.

“Dearborn is home. This is the place that provided my family with social opportunities and financial freedoms,” said Hammoud, who also hired fellow Michigan Public Health alumna and Dearborn native Mariam Jalloul, MPH ’19, as chief strategy officer. “My mother came here in the early ’70s at 4 years old. My father came later in his 20s when my grandfather was trying to find a job on the assembly line in the early ’80s. Dearborn is where they met; Dearborn is where they raised their family; Dearborn’s where I was educated. There’s nothing like advocating and fighting for home, and there’s no place like Dearborn—we’re a phenomenal city. It’s the greatest city in all the land, and that’s why we’re here.

“For me, the top of my list is obviously people who are competent, who are skilled and knowledgeable—but also people who are from this city. I think there’s nothing greater than that servant leadership, leaders who are from the community itself. Dearborn is unique, and I care for Dearborn like no other because I was born and raised here. All my memories are from across this town, and Ali has those same relationships.”

A less traditional pathway

After graduating from Michigan Public Health, Hammoud worked with Marianne Udow-Phillips, MHSA ’78, a lecturer in the Department of Health Management and Policy and a member of the Dean’s Advisory Board. She also is the founding executive director of the Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation.

Hammoud decided to take a less traditional career pathway for an epidemiologist because Udow-Phillips’ influence opened his eyes to the world of policymaking.

“She has this way of bringing policymakers and legislators to the table to connect them with researchers so that it can lead to something productive,” he said. “While I was climbing that corporate ladder, working through her, working through Henry Ford Health afterward, my older brother passed away unexpectedly in 2015. When he passed away, I took that as a moment to recalibrate my life and decided to make a full jump into trying to give back as much as I can in the way that he had. I took all the lessons that Marianne had given me over the years and entered the world of politics.”

Public health is more than just healthcare, Udow-Phillips said. It’s more than basic immunizations and other services that are often confused with the focus of public health.

“Public health is about the conditions in which we live,” she said, “and the conditions in which we live are influenced by every aspect of government. They’re influenced by where we build our roads, how walkable our communities are. They’re influenced by safe water and our whole infrastructure; they’re influenced by our education system. Public health is so integral to every other system. And I think sometimes we think of public health as sort of limited to a public health agency, which is really just one very narrow lens to look at public health.

“I’m not sure how many mayors, if any, besides Abdullah have come up in a public health system or operate with a public health lens. He understands this in a way that’s so much broader than most others, and I’m absolutely convinced that both Abdullah and Ali are committed to it and live and breathe it.”

For Dearborn, Hammoud has adopted a public-health-in-all-policies concept to improve community health and not just individual health.

“If you’re talking about the various health disparities that impact immigrants and people of color throughout the city of Dearborn, the south end of Dearborn and southwest Detroit, it’s the asthma epicenter in the state of Michigan—highest asthma rates in the state,” he said. “That’s a public health problem. If you talk about speeding and reckless driving across the city, that’s a public health problem. If you talk about the disproportionate impact that policing has had on communities of color—primarily Black drivers—in the city of Dearborn, that’s a public health problem.

“If you talk about economic development and the way that you zone a city where you permit industrial zoning in the least affluent, largest concentration of individuals where English is a second language, that’s a public health problem. You’re creating this disparity purposely in the way that you create economic policy, and so, for me, it was without a doubt that the city lacked a public health department. It needed one and more than the traditional brick-and-mortar; what we needed was a public-health-in-all-policies approach where every decision you make checks the public health screening to make sure we’re making the correct decision. And, if so, then it should move forward because it’s a good, sound health policy.”

I’m not sure how many mayors, if any, besides Abdullah have come up in a public health system or operate with a public health lens. He understands this in a way that’s so much broader than most others, and I’m absolutely convinced that both Abdullah and Ali are committed to it and live and breathe it.”

— Marianne Udow-Phillips

The COVID-19 pandemic also played an important role for the establishment of the department.

“When you think about the pandemic, it was both the great disruptor but also the great clarifier,” Abazeed said. “The reason why the United States had by far the worst response to a global pandemic of any developed country is because we’ve dis-invested from public health for four decades.

“We have seen public health responsibility shift from cities—where people know their communities best—to counties. Wayne County is responsible for 1.8 million people and they’re technically Dearborn’s health authority. They can’t reasonably take care of Dearborn the way that Dearborn can take care of Dearborn. The state of Michigan can’t take care of Dearborn the way that Dearborn can take care of Dearborn. Making that case, we should be proud of the fact that we’re just the second city in Michigan to have a health department and not shy away from it.”

Building a ‘pseudo think tank’

Abazeed, who received the C.J. and L.R. Ross Scholarship in Public Health, had the perfect background to be the founding director and chief public health officer of Dearborn Public Health. He earned three degrees from Michigan: a bachelor’s degree in Neuroscience, a Master of Public Health in Health Behavior and Health Education from Michigan Public Health and a master’s in Public Policy. He also was a Presidential Management Fellow for the US Department of Health and Human Services and NIH.

But he still is just one person; he knew he needed support.

“I knew I couldn’t do this alone, and I knew I’d have the mayor and the rest of the executive team,” he said. “I knew I’d have the other departments to support in whatever ways possible, but I needed public health support.”

He reached out to Michigan Public Health’s career services team and similar services throughout the university and started recruiting interns. Abazeed was only looking for 5-7 interns but ended up getting more than 100 applications from students across campus.

“I thought to myself, ‘Well, we need all the help we can get,’” he said. “‘I’m one person, the mayor and the team are all busy. No one can supervise or mentor the students in the way that I hope to do—so why don’t we set up a fellowship system where I’ll recruit four interns to serve as executive fellows? Then let’s take 20, let’s take 30, let’s take all of them if we can.’ And we did.

“I want to make this very clear: Without the School of Public Health and without those interns, we’re not where we are today. They built this department, and we’re so indebted to them and for the work that they’ve done and they continue to do.”

“They became a pseudo think tank, and all my directors started saying, ‘Can we get some help from the public health team?’” Hammoud said.

Public health solutions

In 2021, there was catastrophic flooding in Metro Detroit. Dearborn was severely impacted more than just about any other community with 21,000 of 30,000 homes being flooded.

The city is putting together a public-health-in-all-policies plan on how to spend a $26 million Community Development Block Grant from the federal government to help prevent flooding in the future. Part of the money will be used on permeable pavers instead of typical asphalt so affected areas will retain rainwater for rain gardens as well as other infrastructure updates.

Hammoud offered other tangible solutions to solving municipal problems with a public health approach, including truck traffic pollution and sound pollution from the Gordie Howe International Bridge.

“We have a lot of residential streets that experience a lot of heavy truck trailer traffic, and so one of the public health initiatives we rolled out was banning certain truck traffic on roads that are close to or cut through actual residential streets in the south end, the most populated areas. Another initiative we’re working on now is buying one-mile worth of industrialized private land and creating a new zoning called conservation zoning.

“We’re going to knock down all the buildings and build a hiking and biking path and build a dense shrubbery between that major roadway and the residents living on the other side of it to try to decrease any potential impact by bridge traffic.”

The city also is looking to construct affordable housing near the Fairlane Town Center to help reduce the 9,000 parking spaces to decrease the rate of flooding in the area, but also improve public transit and mobility.

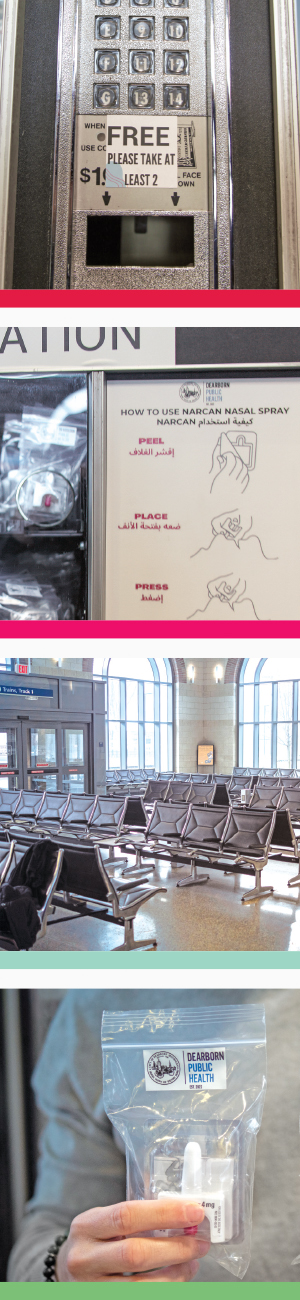

Dearborn Public Health launched a Narcan Vending Station in November in the lobby of the John D. Dingell Transit Center. It allows the public to obtain units of Narcan—a lifesaving drug proven to reverse overdoses—at no cost to residents and in a convenient central location.

“It’s already surpassed 800 units,” Hammoud said.

Udow-Phillips said Hammoud’s perspective on life is fundamental to his success.

“Abdullah’s approach to the world is through a lens of compassion and inclusion,” she said. “He has faced enormous prejudice; he’s faced discrimination against his religion, his creed. He faced it directly in Lansing from fellow lawmakers every day, and yet he never gave up on trying to educate and thinking the best of others. That approach is what we need in this world. His compassion, his humanity, his civility—that defines him too—and that is a very core public health value that he lives every day. I think we have so few of those leaders, and our older leaders could learn so much from him and his values and views of the world.”

Underrepresentation is costing millions

Dearborn is the seventh most populated city in Michigan at about 110,000 people, according to the 2020 Census, but also one of the fastest growing cities in the state, Hammoud said.

“Not only is Dearborn home to the Ford Motor Co., but we’re also the home and capital of immigration,” he said. “When immigrants first touch down in Michigan, they prefer to touch down in Dearborn because of the longstanding history of acceptance and welcomeness to various communities, whether it was the Polish, the Italians, the Lebanese, the Yemenis. The Afghani community right now is really growing.”

The difficulty though, Hammoud said, is underrepresentation—or no representation at all—by the census.

“If you go to the census, we’re 92% white,” he said. “There’s no accurate assessment for capturing the Arab population in the city of Dearborn. If you were to ask me what percentage of the population is Arab, we throw out estimates. We think it’s around 55%. There’s no way to know for sure because there’s no box to check for Arabs on the census. It’s not on the list.”

Hope may be on the way for Hammoud and Abazeed as Dearborn Public Health was awarded a $100,000 grant from the DMC Foundation, a not-for-profit organization that supports southeast Michigan, to conduct the city’s first community health needs assessment.

“We’ve been in touch with the Census Bureau and I’ve been in touch with professors who have helped the City of Detroit file a lawsuit against the Census Bureau for undercounting,” Abazeed said. “We’re exploring our own avenues because we believe that the census is undercounting us anywhere between 5,000 to 12,000 people. Our official numbers are 110,000, but we think we’re close to 120,000, and there are a lot of barriers to why we don’t have that definitive number.”

“From a city perspective—that 110,000—that’s what determines the local revenue sharing formula and the money that you get,” Hammoud said. “If the estimate is off 7% to 12%, you’re losing out on millions of dollars.”

Without the School of Public Health and without those interns, we’re not where we are today. They built this department, and we’re so indebted to them and for the work that they’ve done and they continue to do.”

— Ali Abazeed

‘Our youth has been an advantage’

Not only do Hammoud and Abazeed stand out due to their public health approach to governing Dearborn, but also in their youth. Both are just 32 years old—and so far it has been their secret weapon.

“I firmly believe that our youth has been an advantage,” Hammoud said. “We’re workhorses. I’m not saying that’s always a great thing. You obviously want to have a work-life balance, but we challenge the way things have always been done. And you must have humility to work in public service—arrogance is not going to get you anywhere.

“Public policy is a lever—a lever for change. I can’t sit here and tell you that it takes one hand to pull that lever down; it takes a team. And that’s what we’ve formulated so well here.”

Udow-Phillips said Hammoud’s passion for public health and his vision for governing is contagious.

“Abdullah is just phenomenal because he graduated from college at 19 and started graduate school so young,” she said. “He has always been somebody who has worked hard, excelled and been moved to change the world. He’s just got that energy and that passion, and what I think is exciting about his youth—besides just his own energy—is how inspirational he has been to other youth.”

Abazeed shared an Islamic tradition that fits how he and Hammoud view their responsibilities.

“There’s a beautiful saying: ‘Those who don’t show mercy to our young and respect to our elders are not one of us,’” he said. “That’s something I think about more and more. We have a reverence for those who’ve been here, those who’ve done the work and those who have experience that we don’t necessarily have. We also want to be treated like people who are the same. We have experiences that others don’t have.

“We happen to be Arab American. We happen to be a part of the administration for the mayor who was the first Arab American and the first Muslim American and the first person of color to ever assume this seat for the Arab American capital of North America. I think the joy of being in a position like this is we get to extend that grace and mercy to other people. If there’s someone who shows up with an application for an internship or a job who doesn’t necessarily have experience because they’re working-class, they grew up poor, or they grew up navigating a racist immigration system, then we can extend that offer to someone and say, ‘You have other experiences that don’t show up on a résumé, but we got you because we’re from you and we’re of you.’

“We try to be that every single day.”