Everyone versus Coronavirus: An Epic Public Health Challenge and What the Future Could Hold

A global pandemic has challenged the idea that our public health systems are adequately developed and resourced and has exposed deep needs across those systems. Here are some of the lessons we’re learning, the data we’re collecting and organizing, and the work we’re doing to protect the health of today’s populations and of generations to come.

All eyes are on public health and will be for the foreseeable future.

The Foundation Was Already There

The first reports of a new type of virus that could cause respiratory diseases in humans came in the 1960s. They were soon dubbed “coronaviruses” because the array of the external spike proteins can have a crown-like appearance.

Coronaviruses Old and New

I had just finished a national service commitment in Central America where we confirmed that the same viruses causing illnesses in temperate zones cause illnesses in the tropics when I was brought to the University of Michigan School of Public Health by Thomas Francis to work on respiratory illnesses.

As we learned more about these viruses, we also began observing outbreaks that caused respiratory illness but did not behave nor look like influenza viruses, rhinoviruses, or other viruses that cause respiratory disease.

The first reports of human coronaviruses came in the 1960s, when multiple teams began identifying novel respiratory pathogens, first in a sick child and then in medical students. The viruses were behaving similarly and had a similar morphology, or shape.

They were soon dubbed “coronaviruses” because the array of the external spike proteins can have a crown-like appearance.

In the spring of 1967, a sharp outbreak of a viral infection was detected in the Tecumseh, Michigan, community. Continuous surveillance for respiratory infections had been in progress in Tecumseh since November of 1965. And an extensive study of human blood sera had been collected in that community for eleven years. All of this provided a strong foundation for us to characterize the 1967 outbreak.

This virus tended to spread preferentially within families and primarily impact the respiratory system, as influenza viruses tend to do. Today, we know a lot more about influenza and coronaviruses—and in general, we understand them to be divergent, with coronaviruses more often causing the “common cold” and influenza infections tending to cause more severe illness.

The novel strain of coronavirus causing COVID-19 disease is also unlike the flu in many ways. But one thing it shares with influenza is that it tends to find and rapidly spread through nursing homes and other high-density populations—like prisons and food packing plants.

Every virus exhibits unique behaviors, and every human body responds differently to a viral infection. We have been studying this novel coronavirus for only a few months. We still have a lot to learn.

—Arnold S. Monto, Professor of Epidemiology and Global Public Health and Thomas Francis Jr. Collegiate Professor of Public Health

Monto directs the university’s Household Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Study (HIVE)

and continues to publish broadly on coronavirus occurrence and transmission in Michigan.

He is working on several CDC- and NIH-funded studies looking at the epidemiological

spread of COVID-19.

Stacked Practices

When talking about coronavirus protection, we can use a Swiss cheese analogy. If you think about Swiss cheese, none of the holes are exactly lined up. As you start to stack those layers of Swiss cheese—or imperfect layers of protection, like masks and social distancing—one on top of the other, the holes become covered and, eventually, by stacking enough slices you’ll be able to substantially reduce the risk of infection.

—Ryan Malosh, Assistant Research Scientist in Epidemiology, on the Population Healthy Podcast

Occupational Health Practices Protect Everyone

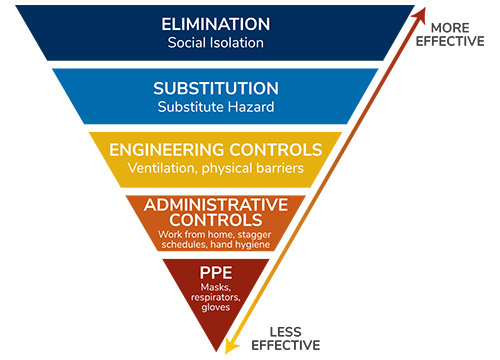

When we think about keeping people safe in the workplace from any hazard—radiation, dangerous chemicals, or this novel coronavirus—we approach risk mitigation by stacking different layers of protection so we’re not relying on a single aspect of risk mitigation to keep us safe. Occupational health provides a whole suite of tools to support this.

Our public health infrastructure provides the first layer of protection, with disease monitoring, modeling, case investigation, and contact tracing. Engineering controls create physical protections from exposure to infectious disease—enhanced ventilation systems, physical features to encourage social distancing, and physical barriers to prevent the spread of respiratory droplets. Administrative measures include the team cultures we build around using these controls, implementing new patterns for worktimes to reduce the number of staff and customers, and the policies we implement around sick leave, telecommuting, and other employment changes that support infection reduction. Personal protections include wearing personal protective equipment wherever necessary and emphasizing personal hygiene, like handwashing, along with sanitation in general.

Many workplaces now realize they have more flexibility and employee enthusiasm than expected. In a very short period of time we’ve seen tremendous ingenuity and resilience across American businesses to drastically reduce our exposure to the coronavirus. Each tactic we engage provides more protection. The more layers we stack, the lower our risk of infection.

—Rick Neitzel, Associate Professor of Environmental Health Sciences

Current Shortcomings of Immunity Testing

Some hope that tests for immunity to COVID-19 could be used to allow people to go back to work, travel, and other activities. But were immunity to become the ticket to reenter society, those without it may face real restrictions on movement, employment, and access to other resources. The implications of such restrictions would not fall equally across society and so could create or exacerbate inequality.

Lack of immunity could also become a source of social stigma, in an ironic twist to how disease stigma has typically occurred throughout history, in which those suffering from the communicable disease—think HIV, polio, and even SARS—face discrimination and exclusion.

Disease and its consequences are influenced by social factors like income, neighborhood, race, and ethnicity. It was true during the 1918 influenza pandemic, the polio epidemic, and throughout history—and with COVID-19, we are seeing it is still true today.

—Denise Anthony, Professor of Health Management and Policy, Director of the Health Informatics program

Crystal Ball or Compass?

The power of epidemiological models is not like a crystal ball, identifying the exact timing of an epidemic. Instead, models are more like a compass, showing the direction of an outbreak within a range of possibilities.

—Joseph Eisenberg, John G. Searle Chair and Professor of Epidemiology

Vaccine Desires

In 1905, the Supreme Court ruled in Jacobson v. Massachusetts that states have the right to mandate vaccines. Smallpox was prevalent, and to promote the health of citizens by ensuring people had adequate immunity, states were granted this right. This has been broadened to include new vaccines that have been shown to protect population health. And yet we find ourselves in a situation where vaccine hesitancy—delaying or refusing childhood vaccines—has become a socially and legally accepted behavior at a level high enough to affect herd immunity.

If and when a coronavirus vaccine is available, will people still want it? Research from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed that, by the end of the pandemic, many fewer people wanted the vaccine compared to the middle of the pandemic. I’m concerned that, if and when a vaccine is available, there might be a large enough proportion of the US population that declines the vaccine that we are not able to achieve herd immunity.

—Abram Wagner, Research Assistant Professor of Epidemiology

Learning More to Address a Pandemic

Humans produce a lot of data, and the current coronavirus crisis seems to have accelerated our production of and engagement with numbers, formulas, graphs, and maps. We can learn a lot from all the statistics, especially if we know how to digest and interpret them.

Antibodies, Vaccines, and Immunity

Antibody tests, or serological tests, search blood serum for evidence that an individual has been infected with a virus. If a person is infected by a virus, their immune system produces specialized antibody proteins that are uniquely equipped to fight off that specific virus—in this case, the SARS-CoV-2 virus. When the serum from a person who was infected with COVID-19 is applied to a small portion or fragment of viral protein immobilized on a solid surface, the serological test will reveal these specialized antibodies.

If accurate and widely available, COVID-19 antibody tests could not only aid in selecting serum for patient treatment but could help determine the true rate of infection and measure the spread of the virus and disease.

If accurate and widely available, COVID-19 antibody tests could not only aid in selecting serum for patient treatment but could help determine the true rate of infection and measure the spread of the virus and disease. Many COVID-19 antibody tests have hit the market, and some are proving too inaccurate to be useful for clinical care or epidemiologic studies.

Our antibody test protocols focus on the spike proteins from the SARS-CoV-2 virus—the proteins on the outer surface of the virus that help it enter our cells. There hasn’t been enough time for us to document infections and resulting immunity, then to follow those cases forward to see if they get infected again in the future.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is a member of the large coronavirus family of germs which includes the SARS-CoV virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and MERS-CoV, which triggers Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). People who have had SARS and MERS appear to retain antibodies to their viruses for several years. We know that the spike proteins that viruses use to invade our cells are exposed and are therefore good targets for the immune system. We also know the spike protein on coronaviruses produces an immune response.

We are working now to extrapolate from what we know about endemic coronaviruses and from SARS and MERS to develop better antibody tests and effective vaccine options. Ultimately, this virus may be different, and continued efforts will be needed to assess the length of immune protection, whether you have recovered from COVID-19 or have received a vaccine for it.

—Aubree Gordon, Associate Professor of Epidemiology

With researchers at the University of Michigan’s Life Sciences Institute, Gordon is advancing a new antibody test to identify people who have been infected with the coronavirus. The test being validated now could accelerate selection of patient plasma for use in treating new COVID-19 infections.

Predictive Models for the World’s Largest Democracy

We are constructing predictive case count models in India to provide projections over

a time horizon under hypothetical and varying public health interventions. Strict

intervention measures for the largest democracy in the world are appropriate. Our

assessments of the economic, social, and health care implications for such interventions

in India led us to this conclusion: Until we acquire biological herd immunity from

COVID-19, there is need for social and economic immunity—not just coverage for testing

and treatment for everyone in India but subsidies and incentives for people to survive

the consequences of these severe interventions needed to stop the virus from creating

a catastrophe in India. We have provided helpful models. The implementation of such

measures is up to policymakers and stakeholders in India and is complicated and fraught

with risk.

We are constructing predictive case count models in India to provide projections over

a time horizon under hypothetical and varying public health interventions. Strict

intervention measures for the largest democracy in the world are appropriate. Our

assessments of the economic, social, and health care implications for such interventions

in India led us to this conclusion: Until we acquire biological herd immunity from

COVID-19, there is need for social and economic immunity—not just coverage for testing

and treatment for everyone in India but subsidies and incentives for people to survive

the consequences of these severe interventions needed to stop the virus from creating

a catastrophe in India. We have provided helpful models. The implementation of such

measures is up to policymakers and stakeholders in India and is complicated and fraught

with risk.

—Bhramar Mukherjee, Chair and John D. Kalbfleisch Collegiate Professor of Biostatistics

Mukherjee and Peter Song, Professor of Biostatistics, lead a team of researchers analyzing epidemiologic data from India to make predictions and recommendations on the spread of COVID-19 in this nation of 1.34 billion people.

Inequality and Sociological Imagination

The virus is spreading widely in prisons. Are people coming in sick because of infection risks in their community or because they have been incarcerated recently due to policies that encourage mass incarceration? Or are they contracting the virus in prison? There may be a lot of transmission in prisons, but we can’t draw a neat box around this porous institution and pretend all of the risk comes from there.

—Jon Zelner, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology

Zelner is working on a study funded by the National Science Foundation about how mass incarceration and segregation impact disparities in the spread of COVID-19.

Digesting All the Data

We need to keep the big picture in mind. Specifically, we need to put COVID-19 deaths in the context of deaths from other causes that take a large toll on our population every day. In the US, about 2.8 million people die every year—that’s about 7,700 deaths each day. As data continues to come in, one thing seems clear: without action, the number of deaths grows exponentially. Even if the death rate from this virus is around 1 percent, if it spreads widely and rapidly it can quickly overshadow deaths from other causes and result in a substantial decrease in a country’s life expectancy.

—Neil Mehta, Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy

Mehta’s research and teaching lies at the intersection of demography, epidemiology, and sociology.

Truth: Coronavirus Affects Some Populations More than Others

The virus is affecting our society in ways well beyond contracting the disease. And those impacts are felt disproportionately depending on who you are and where you live.

Peeling Back the Layers of an Epidemic

The public health effects of COVID-19 are like an onion. The outside layer of the onion represents the immediate outcomes of morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19—what we as a society are mostly focused on right now, two pieces that are extremely urgent, concerning, and demand immediate attention. Once you peel away that outer layer of the onion, underneath it many other layers of public health crises are emerging, including the health effects of social isolation, mental health outcomes, lack of access to health care, or avoiding treatment for fear of contracting disease. This is particularly important for older adults who tend to have higher levels of chronic diseases.

We are likely to see an increase in mortality due to non-coronavirus related diseases

during this time. After that layer would be the population health effects of a deep

economic recession. We know economic recessions have a very strong effect on population

health, especially for mental health. We almost always see increased rates of suicide

during economic recessions.

We are likely to see an increase in mortality due to non-coronavirus related diseases

during this time. After that layer would be the population health effects of a deep

economic recession. We know economic recessions have a very strong effect on population

health, especially for mental health. We almost always see increased rates of suicide

during economic recessions.

—Lindsay Kobayashi, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology

Kobayashi is leading the COVID-19 Coping Study, which aims to inform strategies to support well-being and coping for older adults during the crisis.

Weathering

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black, Latinx, and Native American individuals, and the poor, is extreme and alarming but, unfortunately, not surprising. These populations are subject, over years and decades—even generations—to a broad range of stressors that weather their immune systems, weakening their ability to mount a proper response to the infection and predisposing them to the automimmune attacks (“cytokine storms”) that are often the primary cause of COVID-19 related death.

—Arline Geronimus, Professor of Health Behavior and Health Education

Geronimus studies the phenomenon called “weathering,” in which minorities exhibit weakened immune systems due to the stress of poverty, crime, poor living conditions, sleeplessness, and other factors.

The Role of Racism in COVID-19 Disparities

Many Black Americans have been segregated through redlining policies into neighborhoods with underfunded schools. The segregation caused by redlining combined with lax industry regulations and “not in my backyard” attitudes have placed many industrial polluters in communities of color. This disproportionate exposure to environmental toxicants—a concept known as environmental racism—has left Black Americans to have an asthma prevalence 39 percent higher than White Americans. Put simply, race is not a risk factor—racism is. To say “underlying medical conditions” created the disparity in COVID-19 cases and deaths without highlighting historical and policy contexts is like saying the Flint Water Crisis was caused by lead dissolving off water pipes. While true, it ignores the social context of the disaster. This is just one example of how systemic racism increases coronavirus risk.

—Melissa S. Creary, Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy, and Paul J. Fleming, Assistant Professor of Health Behavior and Health Education

A New Normal Focused on Health Equity

African American, Latinx, and low-income Michigan residents are more likely to live

and work under conditions that place them at greater risk of exposure. This includes

“essential,” often low-wage jobs impossible to perform from home, limiting the ability

to practice social distancing and other protective actions. Racial inequity and poverty

are also linked to multiple chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, asthma) associated

with worse COVID-19 outcomes. This double jeopardy—greater likelihood of infection

and increased lethality of the infection—contributes to the health inequities reflected

in Michigan’s COVID-19 numbers.

African American, Latinx, and low-income Michigan residents are more likely to live

and work under conditions that place them at greater risk of exposure. This includes

“essential,” often low-wage jobs impossible to perform from home, limiting the ability

to practice social distancing and other protective actions. Racial inequity and poverty

are also linked to multiple chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, asthma) associated

with worse COVID-19 outcomes. This double jeopardy—greater likelihood of infection

and increased lethality of the infection—contributes to the health inequities reflected

in Michigan’s COVID-19 numbers.

We now understand in very fundamental ways that a “new normal” must focus on protections for low-wage workers, who—once considered marginal—are “essential” to the continued functioning of critical infrastructure, health, and social care systems. The pandemic has also crystallized the critical role of housing and clean air to protect against the spread of the infection. Consistent with the reality of our “new normal,” these protections are essential components of a public health strategy that values people as critical societal assets, recognizes the interdependence of all our communities, promotes racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic equity, and is well-positioned to protect and sustain the health and well-being of Michigan communities.

From “Building a New Normal: Strategic Actions for Health Equity in a Post-Pandemic World”

—Amy J. Schulz, Angela Reyes, Roshanak Mehdipanah, Linda Chatters, Barbara Israel, and Enrique Neblett

Consistent Access to Food

When the pandemic was declared in March, 4 of 10 low-income Americans were already struggling to afford enough food for their households. Only 18% of them were able to stock up enough food for two weeks.

Using data from a national survey of low-income adults in mid-March, Julia Wolfson, assistant professor of Health Management and Policy and Nutritional Sciences, and Cindy Leung, assistant professor of Nutritional Sciences, measured household food security—the lack of consistent access to food—and challenges to meeting basic needs due to COVID-19.

Coronavirus and Immigration

We welcome any commitment to reduce arrests and the consequential detentions and deportations

that follow. However, we know from years of public health research that a deep mistrust

will still persist and exacerbate coronavirus risk throughout mixed-status immigrant

communities. Put simply, prioritizing certain arrests without explicitly halting collateral

arrests—that is, the arrest of those who are not the target of the enforcement action

but happen to be in the same place at the same time—will not be enough to gain the

community trust needed to halt the spread of coronavirus. Reverting to an enforcement

strategy that has itself been associated with public health harm is too little, and—we

fear— too late.

We welcome any commitment to reduce arrests and the consequential detentions and deportations

that follow. However, we know from years of public health research that a deep mistrust

will still persist and exacerbate coronavirus risk throughout mixed-status immigrant

communities. Put simply, prioritizing certain arrests without explicitly halting collateral

arrests—that is, the arrest of those who are not the target of the enforcement action

but happen to be in the same place at the same time—will not be enough to gain the

community trust needed to halt the spread of coronavirus. Reverting to an enforcement

strategy that has itself been associated with public health harm is too little, and—we

fear— too late.

—William Lopez, Clinical Assistant Professor of Health Behavior and Health Education, and Nicole Novak, PhD ’16, Assistant Research Scientist at the University of Iowa College of Public Health

An Effective Response Requires Team Science

Many of our experts already study aspects of disease prevention and control that were immediately applicable. Others have quickly reassessed and pivoted their work to focus specifically on this outbreak.

Monitoring and Preventing Disease in Michigan for a Safe Return to Work

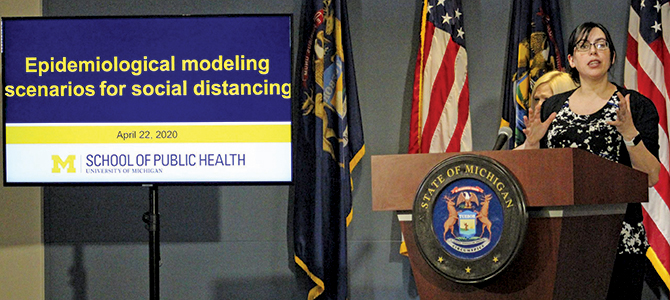

In service to our communities and population health across the state of Michigan, nine researchers from the School of Public Health have been working closely with public health officials and policy makers in Michigan to provide public health modeling and expertise to help state leaders make informed decisions. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer and others are taking input from Michigan Public Health faculty and other experts to make policy decisions about the state’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak and to help Michiganders return to work safely with a public-health-informed plan.

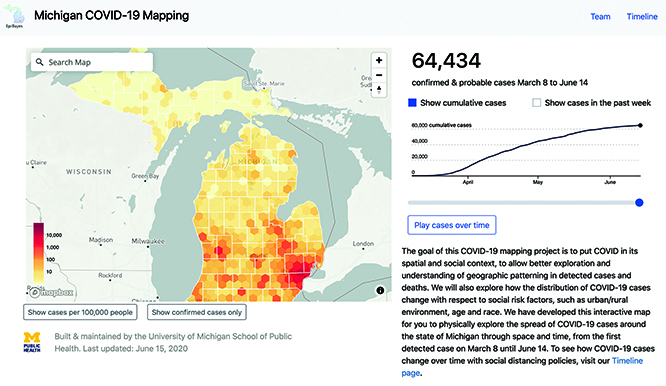

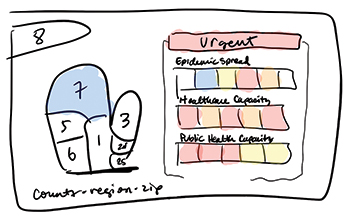

The School of Public Health—in collaboration with the Michigan departments of Health and Human Services and Labor and Economic Opportunity and with the School of Information and College of Engineering—has developed and implemented a precision population health strategy for the state, including publicly available online tools that support the state’s return to work.

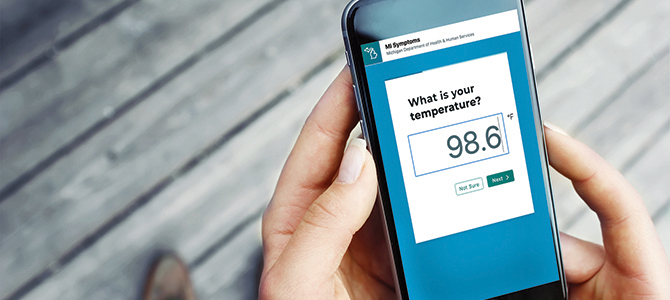

Tools include an online symptoms app designed for employers and employees but available to all Michigan residents. Users enter information daily to help identify symptoms that might be caused by the virus and make decisions about when to seek medical care. Local and state public health officials will use the collective data to identify potential new outbreaks and disease hotspots.

Another tool, the MI Safe Start Map dashboard, uses key public health indicators, such as number of daily new cases per million residents and percent of positive tests, to help local and state public health officials identify and track hotspots that require further attention. A version for the general public lets people look up current risk phases and underlying indicators by region to understand official decisions.

Faculty with expertise in occupational health and safety are working with the state to help inform how workers across different industries can return to work safely.

Modeling for Policy

“We need to find safe ways to reengage with our communities so that we can mitigate the spread of disease and risk while still allowing us to resume some level of economic activity. To do that, we need real-time information on the movement of the epidemic throughout the community so local and state officials can make informed decisions on how and where to reengage.”

—Emily Martin, Associate Professor of Epidemiology

Martin, along with Marisa Eisenberg, Associate Professor of Epidemiology, Complex Systems, and Mathematics, have appeared live during Michigan Governor Whitmer’s press briefings, explaining the models and procedures developed by epidemiologists at the school.

The Risk of Delaying Care

For many types of cancer, the data show delays in treatment lead to worse outcomes for patients. But each time a cancer patient goes to the hospital to receive care, they’re also putting themselves at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. It is essential to balance the need for treatment of a serious disease with the additional risk COVID-19 poses for cancer patients, whose immune systems are often compromised.

—Holly Hartman, PhD Student in Biostatistics

Hartman is lead researcher on a team of data scientists and cancer experts from the School of Public Health and Rogel Cancer Center that developed a free app to help doctors compare long-term risk of postponing treatment with additional risk posed by potential COVID-19 infection.

Virtual Senior Center

Low-income older adults and those with serious health problems are particularly vulnerable to the negative health and social impacts of isolation, and many lack the technology needed to connect virtually with the outside world.

—Mary Janevic, Associate Research Scientist, Health Behavior and Health Education

Janevic is working with colleagues in the School of Information and School of Social Work to evaluate how older adults in Detroit participating in virtual social activities as part of a virtual senior center initiative are coping with the isolation and stress of the pandemic.

Why Should I Help?

COVID-19 has affected people from every community around the world. We are working to learn more about how COVID-19 has affected the lives of people in Michigan who have tested positive for the disease. By choosing to participate in this study, Michiganders will help contribute to our current and future understanding of COVID-19, and help us inform policy and resources for others in the state of Michigan.

—Nancy Fleischer, Associate Professor of Epidemiology

Fleischer is leading the Michigan COVID-19 Recovery Surveillance Study, a collaboration with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to understand the experiences of adults in Michigan with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

For coronavirus-related research from Michigan Public Health

publichealth.umich.edu/covid

For coronavirus-related news updates from Michigan Public Health

publichealth.umich.edu/coronavirus

A Crisis of This Scale Requires Precision Public Health

Many people have heard the term precision medicine. Precision public health is a similar concept with some unique qualities that make it the ideal approach for managing the coronavirus pandemic. Precision medicine is about delivering the right treatment at the right time to the right patient. Precision public health is focused on having the right information at the right time to make the best decision to improve the public’s health. Typically, this involves big data, genomics, wearable devices, and other digital tools to pinpoint needs and match them with appropriate solutions.

Pandemics are too big to address with a one-size-fits-all approach. Widespread stay-at-home orders have allowed us to flatten the curve and alleviate the initial strain on the health care system. But continuing them for too long will devastate the economy, cause other public health consequences, and lead to a frustrated and non-compliant public. We need to use technology and build a culture of positive compliance to help track people’s symptoms well before people think they need a test. This will help local and state public health officials identify early outbreaks in specific regions and address them immediately.

Our public health problems have not evaporated.

Trained as a geneticist, I have been studying precision public health for years and, together with colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, am working with Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s task force focused on economic recovery for the state of Michigan. As part of this work, we collaborated with the state and on-campus colleagues to develop and implement precision public health approaches that engage and educate the public and inform decision-making by the state’s leaders.

Our actions as scientific researchers and communicators alone will not not alleviate the broad effects of this pandemic or any future public health crisis. We need support from government units, nonprofit and community organizations, and the private sector. And we need support and participation from the general public—from me, from you, from my family, and from your family.

Disease outbreaks happen all the time. Pandemics are always a possibility. Dam failures in mid-Michigan caused devastating flooding. Racial, ethnic, and health inequality is causing tremendous suffering in this nation. Hurricane, tick, and heatstroke season are just beginning. Our public health problems have not evaporated.

But the coronavirus pandemic has exposed our deep need for precision public health, built on a robust infrastructure of public health research, practice, teaching, and communication. We need public health to be at its best so that the next pandemic is less severe and the health disparities we live with every day become a thing of the past sooner rather than later.

—Sharon L. R. Kardia, Associate Dean for Education and Millicent W. Higgins Collegiate Professor of Epidemiology

The temperature check screen from the app Kardia and colleagues developed to inform statewide disease tracking and business and policy decision-making across Michigan.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Explore Michigan Public Health's coronavirus research and resources.

- Support research at Michigan Public Health.

Tags

- Spring 2020

- Advocacy

- Big Data

- COVID-19

- Detroit

- Disaster Relief

- Environmental Health

- Epidemic

- Features

- Global Public Health

- Health Care Policy

- Health Equity

- Health Informatics

- Industrial Hygiene

- Infectious Disease

- Lansing

- Leadership

- Mental Health

- Mentorship

- Nutrition

- Policy

- Poverty

- Precision Health

- Racism

- Vaccines