Remote Global Health Internship Is Not an Oxymoron

Q&A with Elizabeth Brines

Master’s Student in Health Behavior and Health Education, Gelman Global Scholar

Elizabeth Brines, second-year master’s student in Health Behavior and Health Education,

embarked on an adventure this summer that was quite different from what she had envisioned.

Brines had hoped to be in India learning from global health partners in community—and

on location.

Elizabeth Brines, second-year master’s student in Health Behavior and Health Education,

embarked on an adventure this summer that was quite different from what she had envisioned.

Brines had hoped to be in India learning from global health partners in community—and

on location.

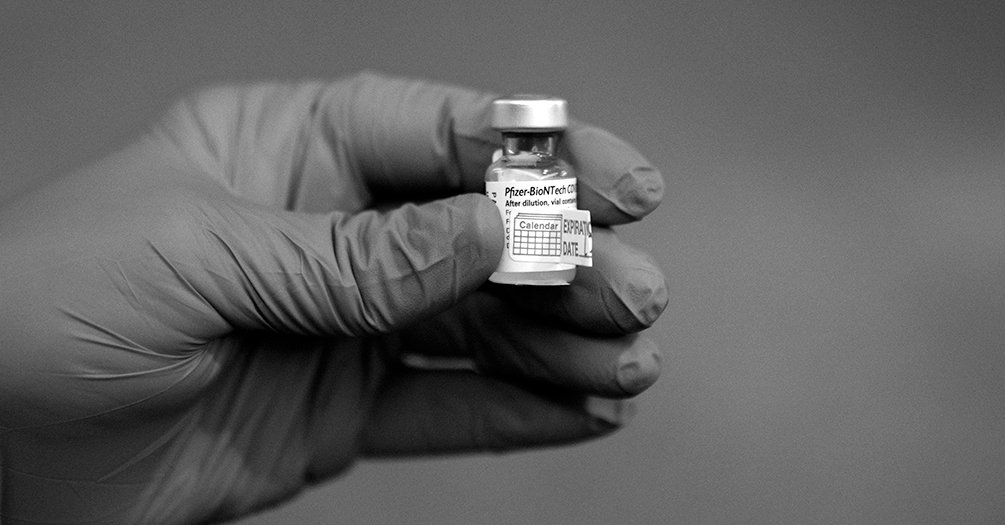

When all global placements were cancelled as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the option to engage remotely in a global health-related project became the only viable option. We asked Brines how she adapted, what she learned from the experience, and what she was able to contribute to public health in Kenya.

What was your first thought when you realized your placement in India had been cancelled?

To be honest, I was relieved. I just knew it wasn’t the right time to be embarking on an on-site international experience. I was incredibly grateful the Office for Global Public Health was able to offer student stipends for remote global internships. I reached out to Dr. Rivet Amico, knowing she does extensive work on global projects, and she came up with several ideas. When she started talking about the PUMA project, I got so excited and I knew it could be a great fit for me.

What is the PUMA project and why were you so excited about it?

The PUMA project is a collaboration between the University of California San Francisco’s Hair Analysis Lab, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), clinicians in Thika, Kenya, who administer PrEP (a drug that prevents HIV infection), and the University of Michigan.

My role was to familiarize myself with a recent PrEP adherence test study that had been done in Kenya and to share the results back with the community. In general, I am interested in improving prescription adherence (and thereby lowering the risk of HIV) through effective monitoring. More importantly for the scope of my role, I think it is essential to involve communities that invest their time and energy into providing useful data with access to the research results. And I knew the PUMA project would give me insights into a research model that does that.

Researchers have an obligation to share the results of studies with participants so they can see how their feedback is contributing to future decisions. By making that collaborative effort to circle back to the participants, we show respect for their insights and build trust in research.

Working with Dr. Kenneth Ngure, a prominent social-behavioral scientist in Kenya, and his research and implementation team, we created materials to communicate the results of the study back to participants and also developed a tool to assist staff with implementing the future point-of-care test.

How does this test factor into HIV prevention and communication measures in Kenya?

The rationale behind the use of a point-of-care PrEP test is to improve our understanding of adherence. Previous studies indicate that young women in sub-Saharan Africa often overreport adherence. Knowing that, this type of test becomes valuable for three reasons.

- Adherence to PrEP dosages and timing is necessary for the drug to be effective. PrEP is highly effective at preventing HIV infection, but only when taken as directed.

- Testing drug levels is a substantially better predictor of PrEP efficacy than self-reporting, especially in populations with known over-reporting.

- Real-time monitoring and point-of-care conversations with providers may be effective at improving adherence.

To create more tools for HIV prevention in Kenyan populations, we need better ways of assessing if patients are taking PrEP in a quantity that actually delivers protection. When implemented properly, this type of test can open the door for conversations around why someone may not be taking their PrEP regularly. Once that conversation begins, providers can work with patients to find new strategies for protecting themselves.

What did you learn about how global health partners work together?

I certainly learned from my remote global health experience how to get creative. Dr. Amico is an original and free thinker, and I learned from her new ways to improvise and play around with what you’re given to produce something unique and hopefully valuable for public health. Before this internship, I never would have listed creativity as one of my skills. But since working with Dr. Amico and working on this project, I’ve found myself becoming more intentionally experimental in bringing elements of creativity into work.

I gained many new perspectives from the PUMA team, including the recognition that I do not and never will have all of the answers. In asking the right questions and being open to feedback from a variety of partners, however, we can together make any product or study stronger than anything I could have come up with on my own. Humility is critical to being an effective public health professional, and this experience highlighted beautifully the value of collaboration.

I also learned how to communicate more effectively with research partners here and abroad and how to adapt to an international context. These skills are critical to engaging in global health work, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to be working with an international team particularly during this time of a global pandemic.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more articles about public health practice at Michigan.

- Support research and engaged learning at Michigan Public Health.

Read More Stories from the Spring 2021 Issue of Findings