Their Lives in Our Hands: The Privilege and Power of Patient-Centered Care

José Gutiérrez

Master’s Student in Health Management and Policy and Business Administration, John R. Griffith Fund Scholar

I was born in California but spent the first four years of my life in Mexico before heading back to Los Angeles, where I lived until I was 22. During my senior year of college, some mentors helped me understand how broad the health care field was—and that is when I decided to pursue health care as a career.

Why are you so passionate about health care and about improving the patient experience?

Regardless of the role we play in this industry, patients are always at the center of it. When we are able to keep patients at the forefront of what we do, our work actually becomes easier and that much more impactful. Early in my health care career, I realized that being in this field is a privilege, that having the opportunity to be part of people’s lives during their most difficult moments is a privilege. Emphasizing patient experience in all that I do is how I thank them for the opportunity to be part of their lives.

Things would have been very different for our family without patient-centered care.

When I reflect on my childhood and the health difficulties my mother faced, I realize that someone, somewhere had the patient experience at the forefront of the work that eventually touched her. Things would have been very different for our family without patient-centered care.

People are putting their lives in our hands. How do we best serve them? How do we ensure their health and well-being? How do we own the complexity of the systems we’ve built and not expect people to navigate our systems? We need to change the structures of health care, to be more fluid so our processes fit people’s lives and acute needs. I owe so much to health care, and I feel privileged to be part of making health care management more trusted, accessible, and patient-centered in every way possible.

Gutierrez with fellow Health Management and Policy students Zechariah Attar and Philip

Cooper at the National Association of Health Services Executives case competition

with an award for their “Know Me, Show Me, Coordinate for Me.” Their case addressed

health care needs among aging adults in the Washington Metro Area, helping them reduce

costs, improve quality, and enhance patient experience.

Gutierrez with fellow Health Management and Policy students Zechariah Attar and Philip

Cooper at the National Association of Health Services Executives case competition

with an award for their “Know Me, Show Me, Coordinate for Me.” Their case addressed

health care needs among aging adults in the Washington Metro Area, helping them reduce

costs, improve quality, and enhance patient experience.

Know Me. Know patients beyond a medical diagnosis. Know their personal goals, daily routines, and best options for behavioral changes.

Show Me. Show patients how to participate in their care. The more patients know about their condition, the better outcomes they are likely to have.

Coordinate for Me. Many patients have multiple conditions. Let systems of care own the complexities this creates—coordination of services, medication delivery, education and training—so that patients can focus on wellness.

There are always two experts in an exam room—the clinician, who is a medical expert, and the patient, who is an expert in their life.

What did your mentors teach you about public health?

Early on, my mentors made me reflect on my personal values and how they tied into public health. I wasn’t told whether they were right or wrong, only to be aware of them, because it can be difficult to separate our personal beliefs from the work we do. I remember them asking me if I believed that having access to health care was a right. I didn’t have to respond to them, but they wanted me to think about it and how this influences the type of work I wanted to pursue.

At the end of the day, I needed to question and change the things we are doing today that are not optimal.

They also helped me understand how my degree, though completely unrelated to health care, prepared me for a career in health care administration. At the end of the day, I needed to question and change the things we are doing today that are not optimal. You would do this in any industry, but in health care, we must remember that people are at the center of these decisions.

How do you analyze upstream and downstream effects on patients?

Michigan Public Health is right across the street from Michigan Medicine, so we can apply our hospital management learning in real time. I’m currently collaborating with colleagues at the Michigan Urology Clinic to develop patient-centered solutions that also work for everyone on the staff.

I have found it very difficult to solve problems from offices and conference rooms.

It is a powerful tool to be able to cross the street and go see a problem or process as it’s unfolding. I can engage with the staff about their processes, ask questions, get their thoughts on what works for them and what doesn’t. In my short career, I haven't found a better tool than simply to go see a process at work. I have found it very difficult to solve problems from offices and conference rooms.

Every hospital produces thousands of pieces of information every day, maybe every minute or second in a larger operation. As a leader, you can’t understand what all of it means and how it fits together if you don’t go and see it and talk to the people who connect those pieces of information every day.

How do you turn all of that into sustainable solutions that really improve care?

Through collaborations that build trust and by relying on processes outside of traditional health care when necessary

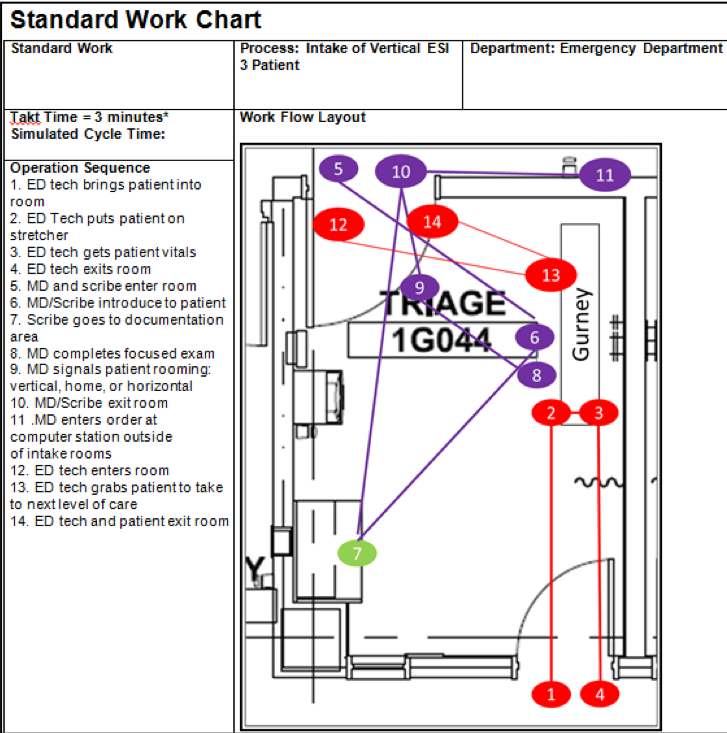

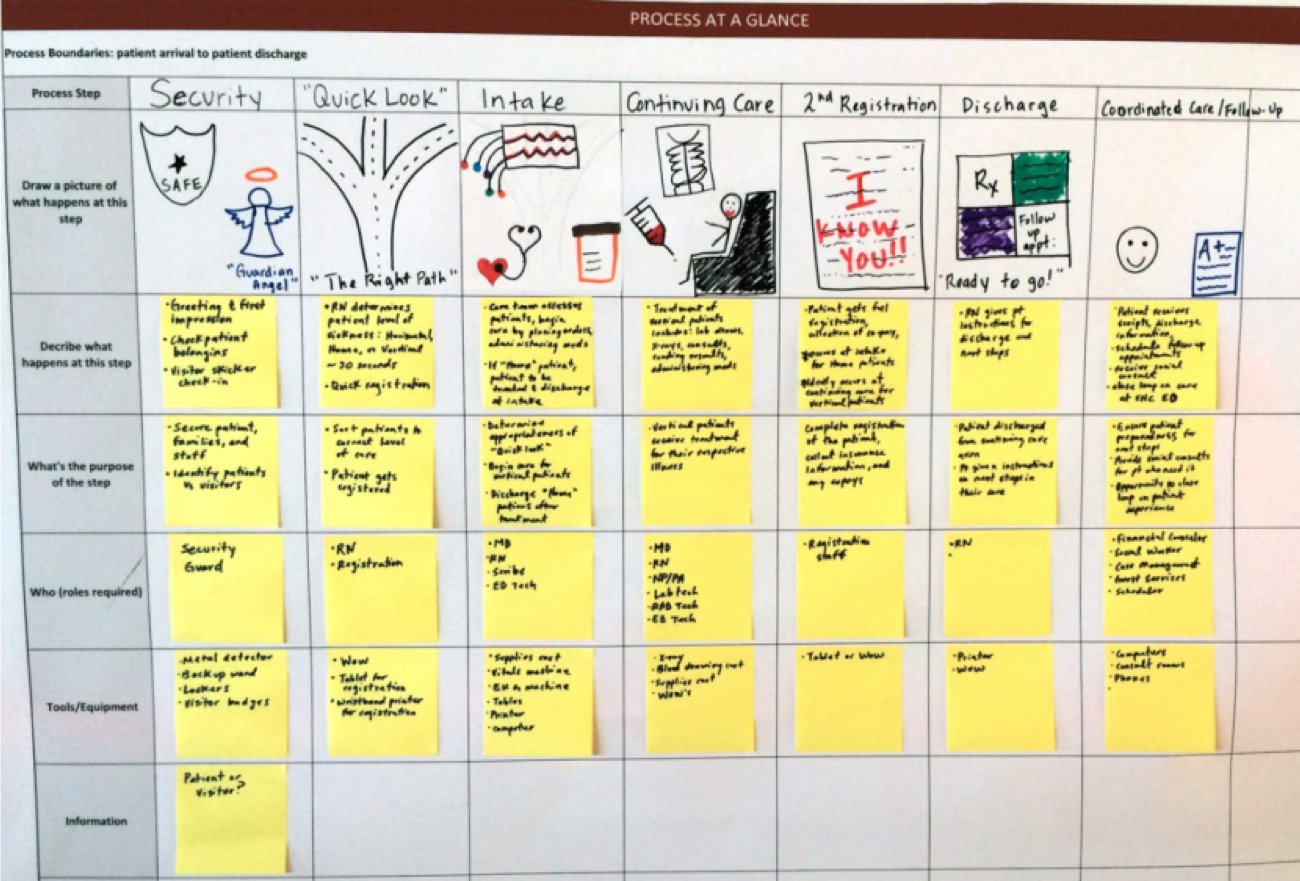

I worked at Stanford Health Care, where I led a team to design the emergency department in their new hospital. It was a challenge not to fall back onto traditional designs—patient rooms here, a nurse station there, intake station over there. We knew we needed to push the limits of what an emergency department could be, but design processes were new to me and everyone in the organization.

We researched other industries and decided to start not with the space itself but with a process of understanding who was coming into the emergency department and why and what staff needs we had in serving those patients. From there, we drew process blueprints on whiteboards and talked through different scenarios—people coming in from ambulances or helicopters, people coming in with various ailments, different staffing arrangements through various shifts.

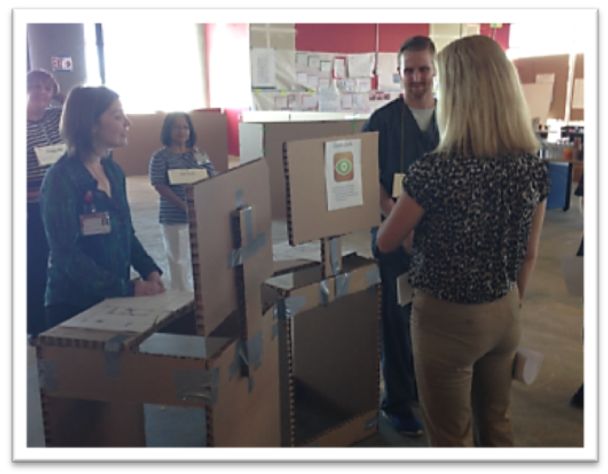

We built an entire emergency department to scale using cardboard.

We had staff in all positions talk through their needs, and then we started building. First, we worked with LEGOs, iterating a bunch of models and working past ideas that wouldn’t work. Then we actually built an entire emergency department to scale using cardboard. We built it, walked staff through it, and then brought in real patients and asked them for feedback.

Why did you go through all of that? Why not hire a design consultant to begin designing the spaces?

Going through a “3P” design (production, preparation, process) isn’t simply about getting the end result—in this case a design for a new emergency department—but about the learnings those going through the process can acquire. Beyond the actual design, my role was to build the capabilities of staff and leaders to think about process and value when making decisions. Having their thinking challenged during these exercises allowed them an opportunity to reflect on and learn about how they might lead differently in a health care environment.

We knew that seemingly small things like door placements and signage make a big difference for staff in the flow of their workday processes. With a real-to-life setting, we could get those details right the first time and have them lead back up to major decisions about walls and spacing and configurations, while perfecting the processes patients and staff actually experience. We got lots of feedback from nurses and physicians, of course, but also from ambulance drivers, lab techs, and other staff.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be part of a process so far out ahead of actually building a medical facility.

All of this was eventually communicated to architects and designers and filtered through

past data as well. As important as anecdotal evidence is, we needed to ensure individuals

perceptions of need were balanced with the community’s cumulative, known demands for

emergency care. And we were basing final designs not on current need but on calculations

for future growth. Our volume had been increasing 6-8 percent annually for several

years, so we wanted to avoid outgrowing the new structure before we even moved

into it.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be part of a process so far out ahead of actually building a medical facility. Our engagement with staff across the system ultimately changed the design of the emergency department and is helping to create a better experience for patients.

- Interested in public health? Learn more here.

- Read more stories about Health Management and Policy students, alumni, faculty, and staff.

- Support research and engaged learning at the School of Public Health.