My Journey to Michigan Public Health

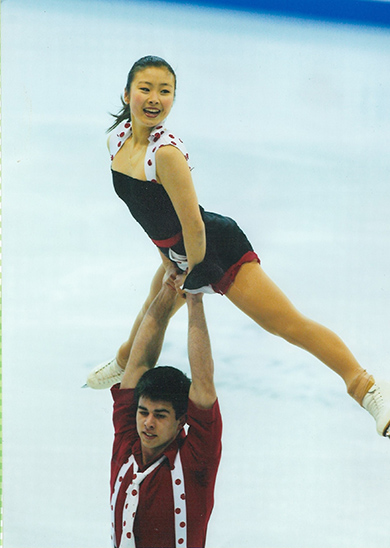

Aya Takai

BA Candidate, Community and Global Public Health

"Overanalysis leads to paralysis!" my coached yelled from the opposite end of the rink, over my program music blaring from the speakers.

As a competitive figure skater, I was an expert overthinker. Whether it was a hypothesis

on gloves giving me a false sense of comfort during my program or a fall being caused

by the trajectory of my right arm pulling me off axis in a jump, I was constantly

trying to figure out what factors were influencing my skating. In a sport where the

slightest hesitation can lead to a major error, overthinking comes with costly consequences.

While it was one of my biggest flaws as a figure skater, my tendency to overthink

eventually led me to public health.

As a competitive figure skater, I was an expert overthinker. Whether it was a hypothesis

on gloves giving me a false sense of comfort during my program or a fall being caused

by the trajectory of my right arm pulling me off axis in a jump, I was constantly

trying to figure out what factors were influencing my skating. In a sport where the

slightest hesitation can lead to a major error, overthinking comes with costly consequences.

While it was one of my biggest flaws as a figure skater, my tendency to overthink

eventually led me to public health.

Figure skating, like many aesthetic sports, values slim, light athletes. Pressure from coaches, judges, and skating partners perpetuates body dysmorphic behaviors among athletes, especially females. Starting skating at the age of 5, I grew up in a community where these behaviors were seen as normal—and necessary for success. After a partner ended a partnership to skate with a "smaller, lighter girl," I struggled with my own body image.

Fortunately, one of my coaches at that time referred me to a sports dietitian. Learning how healthy eating leads to productive training, I was intrigued by nutrition and dietetics, and I started to advocate healthy eating with my peers. But the more I thought about the issue of body dysmorphic behavior in the skating community and sought to understand all of its factors, the more I came to realize that this phenomenon was greater than nutrition and dietetics. Body dysmorphic behavior is deeply rooted in the history and culture of figure skating—in the US and around the world. I came to realize that this phenomenon was in fact a global public health issue.

Last year, I moved to Montreal to train with a new skating partner. Within months,

the partnership was rancid. I was left contemplating about what to do next—in skating,

in

education, in life.

As I walked around the city, emotional and feeling lost, I noticed the homeless. Many seemed to be of foreign descent, perhaps of Asian origins. Montreal, like any metropolitan area, has a large homeless population. After some research and a few discussions with my Montreal-born-and-raised roommate, I learned that a large portion of the homeless population there is not Asian but First Nations—natives of North America.

In this moment, I was alerted to a set of broader and more intricate factors that influence health. The issues I had observed in figure skating had stemmed from history, culture, and decisions made by members of that particular community. For the First Nations homeless of Montreal, factors like political power, legal systems, and structural barriers—ingrained in and compounded by Canada's history—were larger than the community itself and a complex, society-wide matter.

This was my aha moment. And just a few weeks prior, my mother had forwarded me information on a new public health undergraduate program at the University of Michigan. I knew an education in public health was what I needed to further understand complex public health issues such as the ones I had observed in Montreal.

Through my many twists and turns in my skating career, I have learned that life works in odd ways. Like the motley of factors that influence a population's health, so many serendipitous factors led me to Michigan Public Health.

My obsession with overanalyzing cultivated upstream thinking and led to my fascination with public health. I am fortunate to have an opportunity to study at the School of Public Health. The enriching environment here drives my curiosity and passion for public health as I strive to understand the world around me and find my place in improving public health for all.

- Find out more about a Bachelor's in Public Health.

- Support students like Aya.

- Interested in public health? Learn more here.