Digesting the Data: Tips for Understanding and Acting on the Coronavirus Numbers

Q&A with Neil K. Mehta

Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy

Click Here for the Latest on COVID-19 from Michigan Public Health ExpertsAmong the many new things we are learning in the age of coronavirus is that humans can produce a lot of data. To help us sort through some of it, we connected with Neil Mehta, assistant professor of Health Management and Policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Mehta’s research and teaching lies at the intersection of demography, epidemiology, and sociology.

How can we digest the epic amount of data being thrown at us daily during this pandemic?

This is a real challenge for all of us, including those of us who deal with data for a living. My recommendation is that, if you are tracking the epidemic, choose a few reputable sources you like and stick with those. Right now, I am following data put out by Johns Hopkins University, The Covid Tracking Project, The New York Times, and the Michigan Department of Health.

I have been tracking the number of total cases. But I am putting much more weight on the number of deaths.

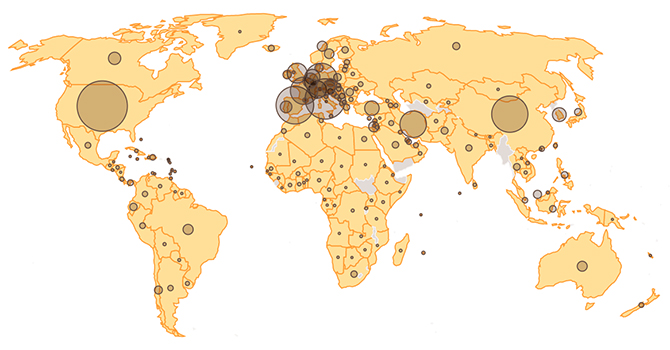

Keep a healthy skepticism with the data as a final word on anything. There is massive variation in the quality of data from one country to another, so we have to be careful when comparing data coming from different countries—and even across US states. Like most people, I have been tracking the number of total cases. But I am putting much more weight on the number of deaths—both total and daily tallies—to track the evolution of the epidemic and see if countries are anywhere near to “flattening the curve.”

Why does focusing on deaths help us understand the numbers?

I focus on deaths rather than case counts because there is a lot of “selection” that goes into testing. By “selection,” I mean that in most countries only individuals who exhibit moderate or severe symptoms are tested. And, importantly, the amount of people tested on a daily basis tends to increase over time, often in response to rising public awareness, fear, and deaths. Therefore, it is hard to get an accurate picture of where a country is in the epidemic by focusing on confirmed cases.

There is far less statistical bias in death trends than in the confirmed number of cases.

This definitely applies in the US, where testing has lagged and is only now ramping up. Daily deaths data is far less susceptible to this sort of “selection” issue, although there are problems with death reporting in many contexts such as in countries with poor death recording systems and where there may be a political interest in suppressing numbers. Nonetheless, there is far less statistical bias in death trends than in the confirmed number of cases. I look at figures that show daily deaths by days or weeks to get the best picture of where we are in the epidemic.

Many of us are tracking the case-fatality ratio—how deadly the disease is, how many of those infected die from the disease. Numbers as high as 3-4 percent were being mentioned, including by WHO. I was skeptical of these initial estimates precisely because of the “selection” into testing. Early on in the epidemic, I tried to identify countries that tested broadly from their population rather than testing only individuals who were very sick. These countries included South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. The case-fatality ratio in these countries were far lower—around 1 percent or less. This is, of course, still very high for a particular pathogen. But because of the more comprehensive testing in these countries, their reported death rate will likely be much closer to the official death rate we establish for COVID-19 in general once the pandemic is past and we can look at all of the data.

Age seems to be a huge factor in the severity of illness and in death rates. Is this just about age or are other factors involved?

Available data indicates that death rates from COVID-19 rise sharply by age. There is also wide variation across countries in the percentage of the population over age 65 and over age 80, where we see significantly high disease severity and death rates. The average age of a population is going to matter for the death rate from this disease.

Population age structure is going to interact with many other relevant factors across the population.

Italy has one of the oldest populations in the world, and that is going to be reflected in their COVID-related death rates. A group from Oxford has done some initial modeling and shown the importance of the age structure of the population. However, population age structure is going to interact with many other relevant factors across the population, including co-residence (multi-generational households) and health care factors. Italy has a large percentage of multi-generational households—many adult children reside with their parents, which is not the case in the US. The interaction of age structure with demographic factors such as co-residence could prove to be a powerful predictor of the impact this disease will have on a population.

What basic principles can you share with us for knowing if and how we should act on any of the data?

First, one of the best tools we have is our collective knowledge from epidemiology on how diseases spread in populations. This spread is often “exponential” in nature, meaning we don’t have only an increase in cases but an increase in the rate of increase. We have strong evidence of “exponential” growth from many historical epidemics. We should absolutely apply this scientific knowledge to the current crisis.

The available international data on hospitalizations and deaths are sending us very clear and consistent signals: without action, the number of deaths grows exponentially.

Second, we should look for consistent signals within the flood of data coming to us every day. Look at data from various countries, which increases our “sample size” and therefore gives us a more solid statistical footing from which to project. The available international data on hospitalizations and deaths are sending us very clear and consistent signals: without action, the number of deaths grows exponentially. Our early figures coming out of the US are highly troubling.

What are we missing in all of this data that we should be paying attention to?

We need to keep the big picture in mind. Specifically, we need to put the COVID-19 deaths in the context of deaths from other causes that take a large toll on our population every day.

Even if the death rate from this virus is around 1 percent, if it spreads widely and rapidly it can quickly overshadow deaths from other causes.

In the US, about 2.8 million people die every year—that's about 7,700 deaths each day. In China's massive population of 1.4 billion, about 27,000 people die each day. China reported about 3,000 COVID-19 deaths. Even if that number is underreported by a factor of 10—say it was actually 30,000 COVID-19 deaths—that still would represent only one extra day of deaths for an entire year, an excess in mortality of about 0.3 percent. That’s a relatively small increase in overall death rates, and it suggests that China’s monumental efforts in controlling the epidemic had a massive benefit to their life expectancy.

Other countries have taken different approaches to control the epidemic, and we have yet to see how large an effect on life expectancy the epidemic will have. We do know that, even if the death rate from this virus is around 1 percent, if it spreads widely and rapidly it can quickly overshadow deaths from other causes and result in a substantial decrease in a country’s life expectancy. This suggests we do need to act and act fast.

The full picture will not be known for a while and will depend on the policies each country adopts to control the spread of the epidemic.

To get a complete picture, it is also important to think about how the epidemic will affect other causes of death. These “indirect” deaths are important to track, and numbers could be as large as deaths directly attributable to the virus. Social and economic dislocations caused by physical distancing policies, for example, could exacerbate deaths from heart disease and many other causes. Meanwhile, certain benefits are also possible, for example, the number of deaths from traffic accidents in China where that number is usually very high and where many have probably been averted. Acute deaths from air pollution are also being studied already, with early indications that the sudden and severe reduction in particulate air pollution will mean fewer of these deaths. The full picture will not be known for a while and will depend on the policies each country adopts to control the spread of the epidemic.

Another fascinating lesson from demographic history, one that always I emphasize with my students, is that nearly every time in modern human history we have experienced a calamitous event like a pandemic or war, death rates and life expectancy recover quickly after it’s over and trends go back to preexisting levels. This is quite remarkable and a testament to our collective human resilience and our ability to adapt to many circumstances.

Photo: NPR

About the Author

Neil Mehta was Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. His research and teaching lie at the intersection of demography, epidemiology, and sociology, and he has active areas of research in aging and disability, immigrant health, race/ethnic health disparities, mortality, obesity, cigarette smoking, and the chronic diseases of older age. Before joining the Health Management and Policy department in 2016, Mehta was assistant professor of Global Health at Emory University and, previous to that, a Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholar at the University of Michigan.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more articles by Health Management and Policy faculty, students, and alumni.

- Support research at Michigan Public Health.