Family’s Holocaust mystery brings two public health professors together

Uncovering a surprising connection between the families of Michigan Public Health faculty members Kate Bauer and Irene Butter

By Isaac Vineburg

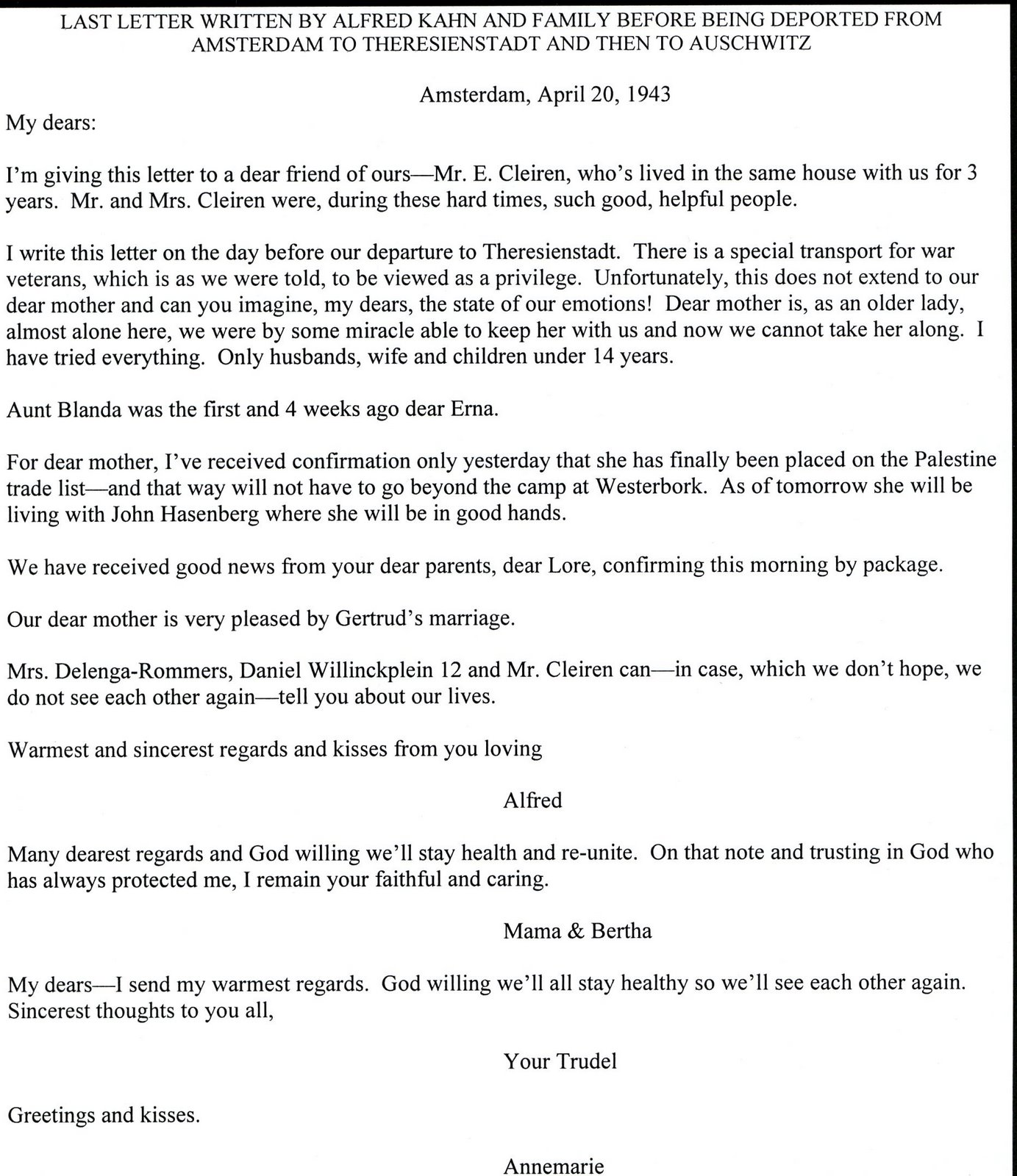

The mystery stemmed from one line mentioned in a family letter from 1943: “As of tomorrow, [Mother] will be living with John Hasenberg where she will be in good hands.” This sparked a search that has lasted decades for Kate Bauer, associate professor of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, and her father, Jim Bauer.

The family letter was written by Bauer’s great-great-uncle, Alfred Kahn, on the eve of his family’s deportation to Theresienstadt, a Nazi concentration camp and ghetto that imprisoned European Jews and acted as a distribution center for deportations to larger Nazi concentration camps and killing centers. The family had been living in Amsterdam after fleeing Germany once the Nazis rose to power.

“This is a special transport for war veterans, which is, as we were told, to be viewed as a privilege,” the letter read. “Unfortunately, this does not extend to our dear mother [...] Only husbands, [wives] and children under 14 years.”

Enter Irene (Hasenberg) Butter, Holocaust survivor and professor emerita of Health Management and Policy at Michigan Public Health. Born in Berlin in 1930 to John and Gertrude Hasenberg, Irene’s family fled Germany for Amsterdam after increasingly restrictive anti-Jewish legislation caused her father to lose his job. She had a happy childhood in Amsterdam, living in the same neighborhood as the Kahns and another German family in exile, the Franks and their daughter Anne.

After the Nazis invaded Holland in 1940, Irene was expelled from school. Jews were barred from public places and public transportation, restricted to certain hours for store purchases, their bicycles were confiscated, and ultimately they had to wear a yellow Star of David patch on their clothing. The Hasenberg family was deported to Westerbork, a transit camp in the German-occupied Netherlands, before ultimately being sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. A brief contact was made with Anne Frank, who was in an adjacent section of the camp.

In 1945, Irene, her brother, mother and father were released from Bergen-Belsen as part of an exchange of foreign nationals, and she eventually made her way to the United States. She attended Queen’s College in New York. From there, she advanced to earn her PhD in Economics from Duke University, where she met her future husband, Charles (Charlie) Butter. Their early career brought them to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where Irene taught in the Department of Health Management and Policy at Michigan Public Health from 1962 to 1996.

A surprising connection

Fast forward to 2024: Kate Bauer, the Michigan Public Health professor, told her father about a Holocaust survivor who spoke at her children’s schools in Ann Arbor. Interested to learn more—and in a potential Amsterdam connection between the families—Jim Bauer researched Butter’s story a bit more, only to find that Butter’s maiden name was Hasenberg, and that her father was John Hasenberg, the man who took in his great grandmother Bertha Kahn all those years ago.

“My dad was like, ‘Holy Cow! Could this be the same person who I’ve been searching for?’” Bauer said.

So, Bauer reached out to Butter, her Michigan Public Health colleague.

“What were the chances that she’s the right family, or that she remembers an older woman named Bertha staying with her family?” Bauer said.

But Butter did remember. She responded almost immediately, stating: “My brother and I loved Oma Bertha, especially as we had to leave behind our own Oma [grandma] in Berlin. She slept in our dining room.”

In addition to Oma Bertha, Butter said: “My brother and I had Hans, the son of Alfred, as a playmate as children.” She even produced a photograph from the early 1940s of herself with Kahn’s son and family, Bauer’s cousins.

“Amazingly, we found the family and the woman who had taken care of my great-great-grandmother, Oma Bertha,” Bauer said. “Irene remembered welcoming her into her own family and home during a very difficult time; she remembered our cousins. And she's alive! She's 93, and has the sharpest memory ever. And then you add on this layer that she was faculty in the School of Public Health, and now I’m faculty at the same school.”

"Two Michigan Public Health professors of totally different generations learn after 80 years that their families lived together during World War II. It’s something I’ll never forget." -Kate Bauer

Butter’s legacy

Butter’s impact on the School of Public Health and the University of Michigan cannot be overstated. In 1990, Butter co-founded the University of Michigan’s Wallenberg Medal and Lecture, an event that honors Raoul Wallenberg, a University of Michigan graduate and Swedish diplomat who rescued tens of thousands of Jews during the Holocaust.

“I always felt I needed to do something like this to acknowledge the gift of being a survivor of the Holocaust,” Butter said in an interview with the U-M Alumni Association.

To this day, the Wallenberg Medal is awarded to humanitarians whose work emulates the human values Wallenberg displayed.

Without Butter continuously educating students about the Holocaust, the connection between the Kahn/Bauer and Hasenberg/Butter families would not have occurred, Bauer said. Butter actively speaks in schools to educate youth about the Holocaust and it was through this activism and engagement that the links were made with the Bauers.

Butter also co-founded Zeitouna (“Olive Tree” in Arabic), an Arab-Jewish women’s dialogue group based in Ann Arbor and composed of six Jewish and six Palestinian women, that has been meeting twice a month for more than 20 years. The group’s motto is “refusing to be enemies.” The connections formed among the women have allowed them to stay committed to each other, especially during times of conflict in the Middle East.

Bringing families together

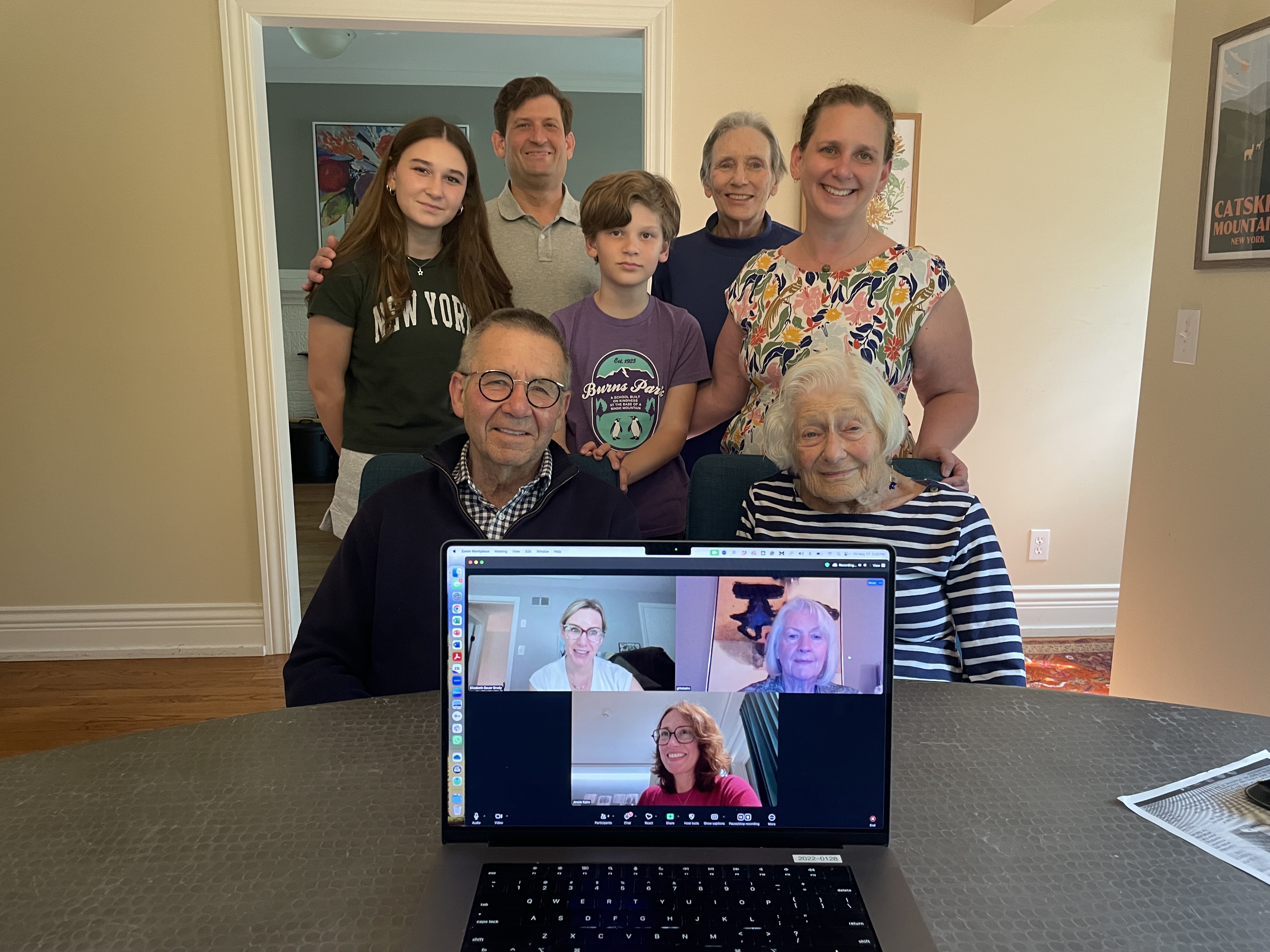

Earlier this spring, Bauer’s parents flew in from New York, and together with Bauer and Kahn cousins video-conferencing in from Germany, met with Butter in Bauer’s home in Ann Arbor, capping off a decades-old mystery and reuniting families who were safe-havens for each other during an unimaginable time of horror.

“Irene was able to share so much about our family and their happy times in Amsterdam before the Nazis invaded,” Bauer said. “She’s also an amazingly kind, thoughtful and intelligent person. She was so excited to hear about my job and what’s going on at the School of Public Health now.”

“Two Michigan Public Health professors of totally different generations learn after 80 years that their families lived together during World War II,” Bauer said. “It’s something I’ll never forget.”

To learn more about Irene Butter, read her memoir, “From Holocaust to Hope: Shores Beyond Shores,” which is co-authored by Kris Holloway, MPH ’96, and John D. Bidwell.

Post Script

Alfred Kahn and his family were deported from Amsterdam to Theresienstadt on April 21, 1943. In September 1943, they were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered.

Not long after Bertha Kahn went to live with Irene Butter’s family in Amsterdam, she was arrested and ultimately deported to Sobibor, where she was murdered.

- Michigan Today: Holocaust survivor, peace activist receives Germany’s highest civilian honor

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more about Irene Butter