Research Abroad: Understanding Local Contexts and Advocating for Change

When researchers engage in projects abroad, their packing lists get long. They need passports and visas and a host of technical tools for work in the field. But they also bring with them the complex histories that exist between their own culture and those of the local communities in which they'll be working. Many of those histories are burdened by memories of prejudice, exploitation, and extractive research practices.

But public health research, by definition, requires working across cultural and national borders to serve vulnerable populations around the world. At its best, public health research generates new scientific knowledge that has the potential to become an advocacy tool benefiting the local community first while providing net gains to all involved. How do we ensure the research we conduct abroad is constructed to achieve this?

Whose Research?

One place to start is by examining the language we use and the attitudes inherent in those word choices. "It is never my research," says Sioban Harlow, professor of Epidemiology and Global Public Health, who has been doing public health research globally for 26 years. She asserts that at times the language used is not partnership language. "Your research usually means a researcher from a high-income country going in with an idea and taking data and maybe sharing some. There's this assumption that we're giving something, as opposed to what we're often doing, which is taking," she says.

If you adopt a different attitude—of working with the community rather than studying

them and telling them what you found—you're more likely to be successful, and results

will be more meaningful and more complete."

–Mark Wilson

Traditional scientific language and processes focus on problem solving, which can magnify one-directional attitudes. One remedy is to leave behind our expectations of solving problems for a local community. "If you adopt a different attitude—of working with the community rather than studying them and telling them what you found—you're more likely to be successful, and results will be more meaningful and more complete," says Mark Wilson, emeritus professor of Epidemiology and Global Public Health, who has been following emerging diseases in Africa, the Middle East, and South America for 43 years.

Mark Wilson at the Agbogbloshie metal salvage dump site in Ghana,

Wilson says this approach also helps avoid outside research teams doing more harm than good, "because as you work closely with local partners who understand the context, you are less likely to treat the people involved in the project as subjects and remember that they are their own agents."

Known Approaches

Certain approaches to research translate particularly well to international research. "One example is community-based participatory research," says Marie O'Neill, professor of Environmental Health Sciences and Epidemiology who studies air pollution, environmental equity, and susceptible populations in the US and in Latin American cities. "The idea is to involve members of the community in every step of the research process, work with them as experts, and return results in understandable, useable formats—these basic approaches can be applied to just about any research where humans are involved."

"If you are going abroad for any kind of research, it should start with ensuring equitable

research standards."

—Chanese Forté

Another example, the Research Fairness Initiative (RFI), was developed specifically for international settings. Sponsored by the Council on Health Research for Development, a global nonprofit championing sustainable health research in low- and middle-income countries, the RFI provides guidelines for establishing equitable partnerships between research institutions from low- and middle-income countries and governmental, nonprofit, commercial, and academic research organizations from high-income countries. "The RFI has been influential in looking at research equity and offering guidance on how to create a contract that's fair and equal between countries," says Chanese Forté, a PhD student in Environmental Health Sciences working on environmental toxicology and occupational health in Thailand. She says, "if you are going abroad for any kind of research, it should start with ensuring equitable research standards."

The RFI provides guidelines around multiple topics spanning the entire research process—from ensuring that the research project is relevant to the local community to determining how data is stored, used, and owned—that institutions should address when developing equitable partnerships. Other similar efforts to address equity in research include the Swiss Commission for Research Partnerships with Developing Countries and the TRUST project.

Researching the Research

Site-specific preparations can begin long before departure. Developing a working understanding of the host culture and learning a few phrases in a local language can go a long way, researchers say. Researching local laws and political situations relevant to your research project "not only gives you an idea of what you might encounter on site but can also aid in the grant writing process and in setting up the initial structures of the project," says Sarah Gutin, a PhD student in Health Behavior and Health Education who researches sexual and reproductive health in Botswana.

"Depending on your location, remember that not everyone can speak freely. When you

arrive on site, listen not only to what people say but to what they're not saying."

—Sarah Gutin

Knowing cultural subtexts can make researchers safer, help them manage the research itself, and often leads to more accurate data. "Depending on your location, remember that not everyone can speak freely," says Gutin. "Thorough pre-departure preparation can set the stage for unexpected revelations. When you arrive on site, listen—not only to what people say but to what they're not saying."

That careful listening can begin here at Michigan, where international students and scholars are active members of our community. In the School of Public Health, the Office of Global Public Health regularly hosts visiting international scholars, offers collaborative research and mentorship opportunities, and facilitates workshops around the world. Faculty can participate in training programs like the NIH's Global Health Training Program, which funds projects in which researchers from high-income countries partner with researchers from low- and middle-income countries.

Building Capacity

Resource discrepancies are a main reason vulnerable populations are vulnerable in the first place. Research capacity—the ability to fund and carry out successful research—is an aspect of that vulnerability which public health researchers can address directly. If our goal truly is to improve population health, we must look through each current project to ask how this particular community might one day be able to conduct this research on its own.

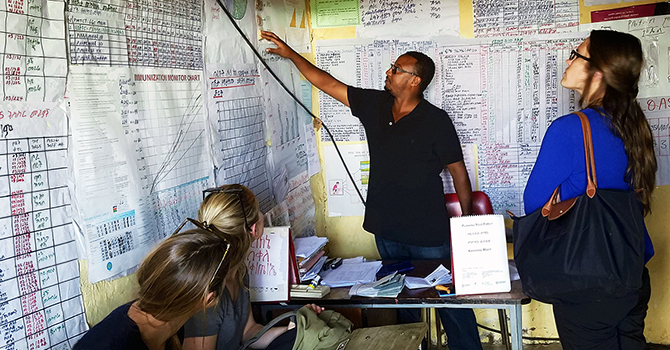

The technical capacities of local researchers are significant obstacles to this kind of independence. "Local researchers may be involved, but they may not have the skills or knowledge to be equally engaged," says Lia Tadesse Gebremedhin, MD, who recently returned to Ethiopia to continue her work there after three years as program director at the Center for International Reproductive Health Training (CIHRT) at the University of Michigan. "For academic partnerships to be mutually beneficial, those in middle- and low-income countries need to benefit according to their gaps, and those gaps tend to be in skill development and participating as equals in collaborative research projects." CIHRT includes local researchers as principal investigators on their projects and as coauthors on publications, which gives local researchers more visibility and authority in their field of research.

Capacity building also helps the entire community push through a major barrier in advocating for themselves: a lack of access to scientific information. "Without data, it is difficult for local advocates to achieve policy change," says Kyle Grazier, Richard Carl Jelinek professor of Health Services Management and Policy, who has been researching behavioral health and social systems in international settings as a Fulbright Scholar in Croatia for the past year. "If we can engage key advocates and provide research data to them in useable, easily understood formats, we can help facilitate partnerships between researchers and policymakers that will benefit the community well after our research team has departed."

Public Health for the Greatest Good

Research that is true to public health will first do no harm. But the best research not only improves community health but moves communities toward self-sustainability and ensures they remain in full control of their narrative and their destiny. "These are people's lives, and it ends up being their data, their story," says Gutin. "We have to remember that the information generated belongs to the community." In this way, capacity-building research always has an end-goal of producing researchers from the local population who can conduct their own successful research.

Research in global contexts adds complexity to an already complex process. Despite the additional efforts and risks, Harlow hopes researchers continue to look for international research opportunities. "It's easy to work in comfortable settings. It's difficult to work in areas where the greatest needs are," she says. "US institutions have to do a better job of engaging where it's difficult, where change is needed most. The goal of public health is to be in the areas with the greatest need, to strive to understand local contexts, and to advocate for change."

Despite our complex histories, public health researchers should be up to those tasks.

Medical residents at the Evangelical University of Africa's Panzi Hospital

Tags

- Environmental Health Sciences

- Epidemiology

- Faculty

- Health Behavior and Health Equity

- Health Management and Policy

- PhD

- Staff

- Students

- Advocacy

- Child Health

- Community Partnership

- Environmental Health

- Epidemiology

- Global Public Health

- Health Behavior and Health Equity

- Health Communication

- Health Equity

- Health for Women

- Policy

- Practice

- Research