Kids and Guns: Geography, Race, and Policy

This is the third article of a 3-part series. Read part 1, Kids and Guns: Safety First and part 2, Kids and Guns: Access to Firearms.

In May, University of Michigan professors Marc Zimmerman, Marshall H. Becker Collegiate Professor of Public Health, and Patrick Carter, assistant professor of Emergency Medicine presented "Kids and Guns: Prevention Strategies," a community conversation in Dexter, Michigan, to help local residents understand the risks associated with youth exposure to firearms and strategies for mitigating those risks.

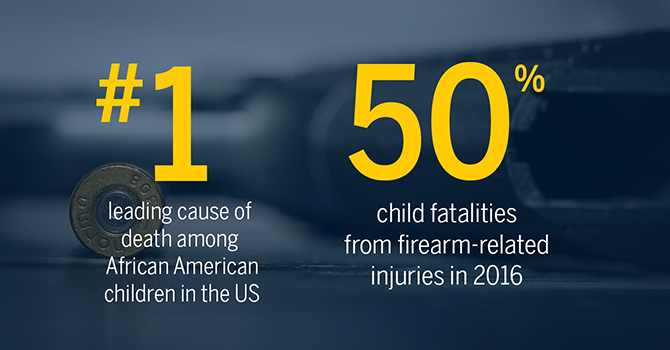

While gun violence is the second leading cause of death among children across the US, it is already the leading cause of death for African American children. "We know that African-American children are over 8 times more likely than white children to die of homicide," said Zimmerman. "That is a terrible reality to ponder, but it helps us know where to focus certain interventions, many of which have been tremendously successful. Without even discussing firearms, we have strategies to build up communities in ways that change environments to reduce crime."

Zimmerman discussed the "greening" intervention studies he and colleagues have led in Flint, Youngstown, and other urban areas. "At-risk youth benefit from very simple interventions to improve the physical environment. Just mowing vacant lots increases a sense of belonging in a neighborhood and encourages residents to spend time outside connecting with each other and participating in physical activity," he said.

"We've coded injuries in the emergency department to specific neighborhoods, and we

can see the reduction in crime in the neighborhoods that have done vacant-lot remediation

and other community greening projects."

—Patrick Carter, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Zimmerman described a common narrative of neighborhood decline but added a hopeful twist: "One broken window goes unrepaired, sending the message that the area isn't cared for, which leads to more broken windows and increasingly significant damage to the built and human environment. But we are finding the opposite is true too. When one neighborhood engages in greening projects, adjacent neighborhoods see the benefits and want to do the same, and the positive effects of improving neighborhoods helps to reduce crime and injury from intentional causes."

Carter has led studies that put a finer point on Zimmerman's greening interventions. "We've coded injuries in the emergency department to specific neighborhoods, and we can see the reduction in crime in the neighborhoods that have done vacant-lot remediation and other community greening projects," he said. "Furthermore, these studies have also shown a very welcome side effect—chronic disease in those same neighborhoods was reduced because people felt safe enough to go out for a walk and engage their neighbors. Physical and mental health are improved for entire communities."

In the United Kingdom in the mid-twentieth century, easy access to carbon monoxide led to a rash of suicides. When sources of heating were changed to natural gas, an observable side effect was a decrease in carbon monoxide related suicides.

Discussing guns and public health without broaching matters of policy is difficult. "With any other epidemiological issue, public health researchers identify, characterize, and mitigate the epidemic as best as they can," Carter said. He provided historical examples of policies and the impact that they can have around self-inflicted deaths.

In the United Kingdom in the mid-twentieth century, easy access to carbon monoxide led to a rash of suicides. When sources of heating were changed to natural gas, an observable side effect was a decrease in carbon monoxide related suicides. In Sri Lanka, farmers were using the toxic pesticides they spray on their crops as their lethal means of choice in suicide attempts. In the 1990s, restrictions on access to these pesticides helped national suicide rates drop by half.

Carter also compared firearm violence to vehicle-related deaths, comparing historical injury rates and automotive safety protocols: "If you can remember the 1950s, you'll recall that cars did not have seat belts, and kids could sit—or stand—in the front seat. Automobile manufactures were originally against mandatory seat belts. Public health research and public outcries for change led to requirements around seat belt installation and usage. Today, safety is a central part of how car companies market themselves. Can a similar movement help lead us to safer behaviors and technologies around firearms?"

The Kids and Guns presentation was hosted by Saint James Episcopal Church as one of its Coffee & Conversation events, which are free and open to the public. Zimmerman and Carter's data-narrative combination was helpful to audience members in comprehending the details of these issues and feeling equipped. "I was really excited to learn about Dr. Zimmerman's greening projects and the multiple benefits they had on communities, including improved physical health. I'll be sharing these studies and stories with my colleagues," said Calisa Tucker, a teacher at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, who attended the May event.

This is the third article of a 3-part series. Read part 1, Kids and Guns: Safety First and part 2, Kids and Guns: Access to Firearms.