Smoking Truth to Smoking Powers: Big Business Meets Public Health

Kenneth E. Warner

Avedis Donabedian Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of Public Health, Professor Emeritus of Health Management and Policy, Dean Emeritus

From the beginning, there was deceit.

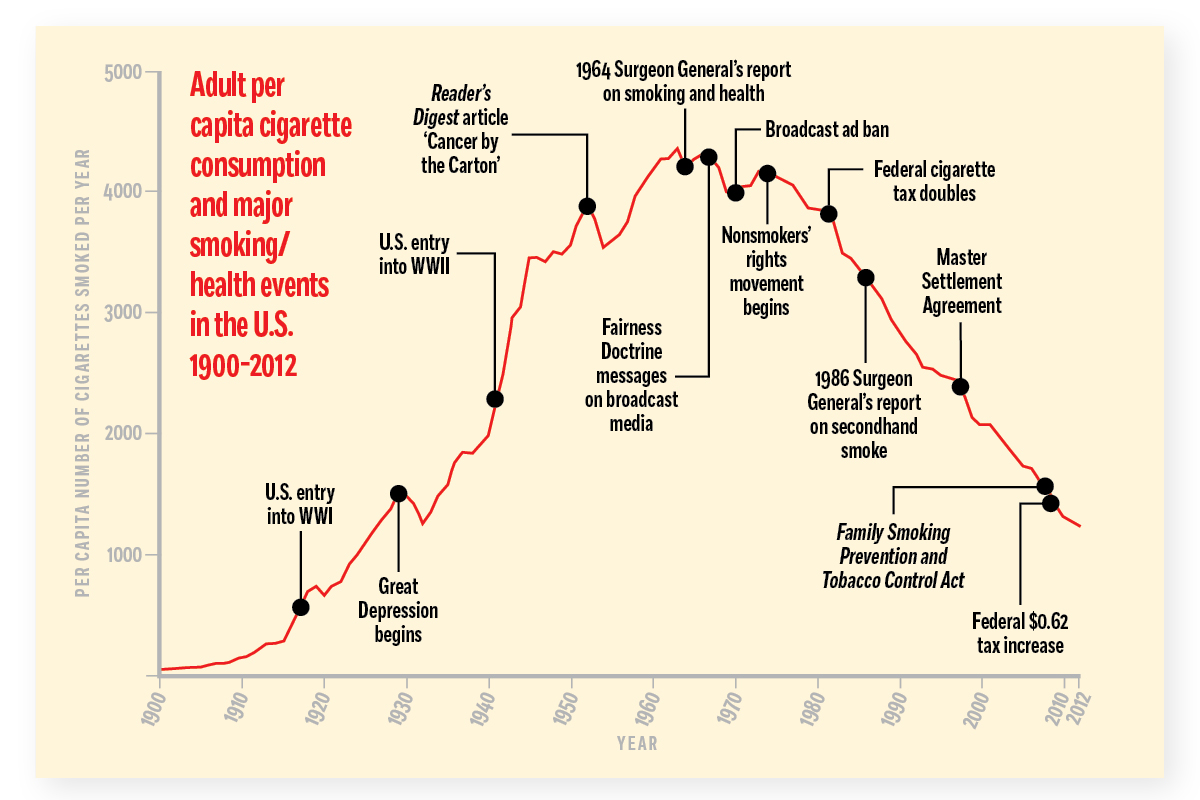

In January 1954, the CEOs of every major US tobacco company gathered in New York City to plan a coordinated response to the devastating public reaction to a major smoking-and-cancer scare. Just over a year earlier, Roy Norr had popularized the findings of new scientific research indicting smoking as a cause of lung cancer in his Reader's Digest article titled "Cancer by the Carton." Read by millions, the article led to a sharp two-year decline in smoking, the first since the Great Depression. The industry was as scared by plummeting sales as smokers were by the news about lung cancer.

The industry execs responded by publishing a "Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers" on January 4, 1954, in more than 400 newspapers in the US, reaching over 40 million people. Accompanying the promise of a new research organization—whose sometimes-damning findings the industry would consistently dismiss—the "Frank Statement" asserted that there was no proof that smoking caused lung cancer. The CEOs went on to say: "We accept an interest in people's health as a basic responsibility, paramount to every other consideration in our business. . . . We always have and always will cooperate closely with those whose task it is to safeguard the public health."

The "Frank Statement" was Exhibit A in a decades-long "brilliantly conceived and executed" strategy in which the industry had consciously striven to "create doubt about the health charge without actually denying it."

The number of adults who smoked rose steadily from 1900 to 1952, except during the Great Depression when manufactured cigarettes became difficult to afford. When sales dropped in 1953 and 1954, Big Tobacco responded by marketing filtered cigarettes, sold as "letting the flavor through" while blocking the substances that cause cancer. Ads for Kent cigarettes claimed its new filtered cigarette was the only cigarette to "show you proof of greater health protection."

Industry documents prove that the purpose of filters was not risk reduction but rather public relations, to reassure the public that smoking was "safe" again and that they did not have to quit smoking. Ironically, it was later learned, Kent's Micronite filter was made of asbestos.

But the ads worked. Smoking resumed its upward trend in 1955. Adult per capita cigarette consumption soared, reaching its all-time high in 1963. Then, on January 11, 1964, the government issued Smoking and Health, the first Surgeon General's report on the dangers of smoking. Coverage of the report ranked it among the top news stories of the year. From January to March, adult smoking plummeted by 15%. By the end of 1964, however, smoking was down only 5%, demonstrating the powerful grip of nicotine on its users.

In the years since the first Surgeon General's report, smoking claimed the lives of 20 million Americans.

Still, broad publicity on the report's findings halted six decades of nearly uninterrupted annual increases in per capita consumption. With few exceptions, smoking has declined annually in the subsequent 54 years. The forces of public health have secured cigarette tax increases and smoke-free workplace laws, restrictions on advertising, prohibitions of sales to minors, anti-smoking media campaigns, the development of smoking cessation treatments, and litigation against the tobacco industry.

Research estimates that the tobacco control movement avoided 8 million premature smoking-produced deaths from 1964–2012. On average, each of the beneficiaries gained 20 years of life. Tobacco control measures accounted for 30% of the entire life expectancy gain from 1964–2012 for Americans over age 40.

Such numbers indicate why tobacco control rates as one of the great public health success stories of the past half century. Yet sadly, smoking remains our country's greatest cause of premature, preventable mortality, responsible for nearly a fifth of all deaths. In the years since the first Surgeon General's report, smoking claimed the lives of 20 million Americans.

The portrait of who smokes today has changed dramatically from a few decades ago. In the 1950s, over half of all men smoked, including doctors, and smoking among women was rising rapidly. Today, America's smoking marketplace is dominated by those with less education and income. Notably, a disproportionate number of smokers are people suffering from mental illness and other forms of substance abuse. For example, most of the victims of today's opioid crisis are smokers.

The percentages of both adults and youth who smoke are falling steadily in the US and throughout the developed world, but in some low- and middle-income countries, smoking is on the rise. All told, a billion citizens of the globe are smokers, including a third of men over the age of 15.

Now the ever-fascinating tobacco marketplace is morphing once again. Electronic cigarettes have become a familiar part of the American landscape. Heat-not-burn devices, not yet sold in the US, have captured over 10% of the nicotine market in Japan in just two years. Cigarette sales in Japan fell by a breathtaking 14% last year alone.

To some in public health, these novel lower-risk devices threaten the "renormalization" of smoking. To others, they represent an opportunity to disrupt the market and replace far more deadly cigarettes. The debate has created a bitterly divided tobacco control community as we enter a new era in dealing with an old problem.

This article first appeared in the spring 2018 issue of Findings, the magazine of the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

About the Author

Kenneth E. Warner is Avedis Donabedian Distinguished University Professor Emeritus

of Public Health, Professor Emeritus of Health Management and Policy, and Dean Emeritus.

He has been engaged in tobacco policy research for over 40 years.

Kenneth E. Warner is Avedis Donabedian Distinguished University Professor Emeritus

of Public Health, Professor Emeritus of Health Management and Policy, and Dean Emeritus.

He has been engaged in tobacco policy research for over 40 years.