Supporting African American Women in Breastfeeding Can Help Increase Health Equity

Amani Echols

Bachelor’s Student in Public Health

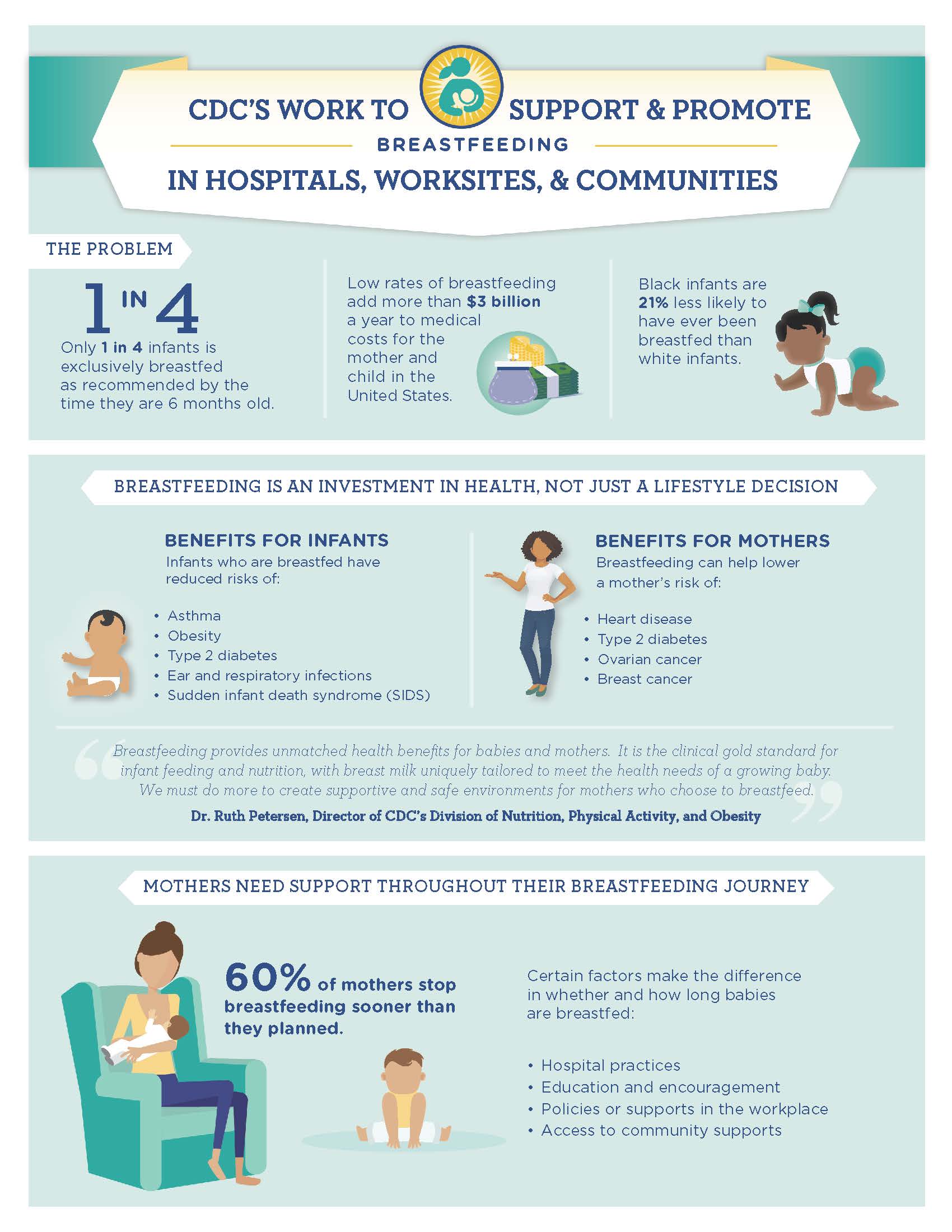

Although exclusive breastfeeding has been linked to numerous health benefits for both moms and babies, 1,2 the US breastfeeding rate is remarkably low compared to other developed nations, ranked 26 globally.3

What's even more concerning is that African American women in the US have lower breastfeeding rates compared to women of other races. Only 68 percent of African American women initiate breastfeeding after having a baby, compared to 85.7 percent of white women, and 84.8 percent of Hispanic women.4 Rates are much lower for exclusive breastfeeding at six months and one year. At six months, rates drop to 41.5 percent of black women, 60 percent of white women, and 52.5 percent of Hispanic women have breastfed.4 By one year after birth, they drop to 21.5 percent of black women, 37.8% of white women, and 31.7% of Hispanic women.4

Breastfeeding should be encouraged as a cultural norm requiring family and social support, which is a significant predictor of intention to breastfeed among pregnant African American women.

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) is a global effort launched by the WHO and UNICEF to implement practices and policies that protect, promote, and support breastfeeding in hospitals. This initiative outlines Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding that strive to provide support and education to mothers through evidence-based policies and practices. Overall, Baby-Friendly hospitals have increased breastfeeding rates compared to non-Baby-Friendly hospitals.5,6,7 However, even in Baby-Friendly hospitals, fewer Black women breastfeed compared to women of other races.

Baby-Friendly hospital policies stress the role of health care professionals in protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding but do not embody the environmental, social, and cultural understanding of African American women's infant-feeding behaviors.

Breastfeeding should be encouraged as a cultural norm requiring family and social support, which is a significant predictor of intention to breastfeed among pregnant African American women.8 Social support includes empowerment and encouragement to breastfeed, the transferring of knowledge about breastfeeding within family units and social circles, and having breastfeeding role models that new mothers can consult. Positive social support has the capability to foster confidence in a mother's ability to breastfeed.

To achieve this public health objective, health care providers and advocates need to offer more breastfeeding support to African American moms.

The BFHI must be inclusive to the demands and intersectional experiences of African American women to more effectively increase their breastfeeding rates. There are several ways to make Baby-Friendly policies more effective for African American women:

- Add an 11th step to the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding: "Educate family, friends, and other support people about the benefits and management of breastfeeding." This step should be led by community health educators.

- Collect all breastfeeding data from Baby-Friendly hospitals in one large data set categorized by race/ethnicity and other identity groups.

- Increase research on the impact of the BFHI on African American women's breastfeeding behaviors.

- Improve participation in Step 10, which focuses on fostering the establishment of breastfeeding support groups.

The African American population could benefit from additional breastfeeding benefits, including decreasing the rate of infant deaths and fostering mother-child bonding that could contribute to stronger familial ties, healthier relationships, and emotionally healthier adults. All of these benefits could improve the overall health of the African American population.9

This research is based on the article published in the University of Michigan Undergraduate Journal of Public Health Volume 2 titled "Mother Nurture: Making Baby-Friendly Hospital Policies More Health Equitable for African American Women."

References

- Bartick, M. C., Schwarz, E. B., Green, B. D., Jegier, B. J., Reinhold, A. G., Colaizy, T. T., . . . Stuebe, A. M. (2016). Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(1), e12366. doi:10.1111/mcn.12366

- Eidelman, A. I., Schanler, R. J., Johnston, M., Landers, S., Noble, L., Szucs, K., & Viehmann, L. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129, e827–e841.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—Social Policy Division—Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs. (2009, January 10). CO1.5: Breastfeeding rates. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/ els/family/43136964.pdf

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Data, Trend and Maps [online]. [accessed Oct 22, 2018]. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/data-trends-maps/index.html.

- Merewood, A., Mehta, S. D., Chamberlain, L. B., Philipp, B. L., & Bauchner, H. (2005). Breastfeeding rates in US Baby-Friendly Hospitals: Results of a national survey. Pediatrics, 116, 628–634. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1636

- One Hospital at a Time Overcoming Barriers to Breastfeeding. (2011). Retrieved from http:// www.calwic.org/storage/documents/factsheets2011/2011cabreastfeedingratereport .pdf

- Philipp, B. L., Merewood, A., Miller, L. W., Chawla, N., Murphy-Smith, M. M., Gomes, J. S., . . . Cook, J. T. (2001). Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative improves breastfeeding initiation rates in a US hospital setting. Pediatrics, 108, 677–681. doi:10.1542/peds.108.3.677

- Spencer, B. S., & Grassley, J. S. (2013). African American women and breastfeeding: An integrative literature review. Health Care for Women International, 34, 607–625.

- Reeves, E. A., & Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2015). Infant-feeding practices among African American women: Social-ecological analysis and implications for practice. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26, 219–226. doi:10.1177/1043659614526244

About the Author

Amani Echols is senior at the University of Michigan School of Public Health working

toward a Bachelor of Arts in Community and Global Public Health with a Gender and

Health minor. She initiated her research on Baby-Friendly hospitals during the 2017

Summer Enrichment Program at the University of Michigan. Echols is interested in how

the health status of populations that are most vulnerable and marginalized strongly

reflects flaws and inefficiencies in the US health care system and social and health

policies. She hopes to address the lack of affordable, accessible, and quality health

care for women, mothers, and children.