Treating Hypertension: A Public Health Success Story

Edward J. Roccella

MPH '69, PhD '77, Health Behavior and Health Education

One of the most successful public health programs in the past century provides an example of what can be accomplished when the government, the private sector, academia, and community organizations work together. The year 2017 marked the 45th anniversary of the establishment of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Since its inception in 1972, this public-private partnership contributed significantly to an 80 percent reduction in strokes and a 70 percent reduction in heart attacks in the United States and is considered one of the greatest public health achievements of the twentieth century.1

The history of the treatment of hypertension is remarkable and replete with stories of prominent individuals who had elevated BP and experienced all of its complications. Woodrow Wilson had hypertension and experienced several strokes as president of Princeton University and governor of New Jersey. As President of the United States, he experienced a near fatal stroke that left him a severe invalid for the last years of his presidency. Franklin Roosevelt's BP began to rise to above normal levels in the 1930s and was especially high in the last year of his life. Roosevelt exhibited all of the complications of untreated hypertension—small strokes and severe enlargement of his heart, heart failure, and progressive kidney disease. He died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage in April 1945 at the age of 63.

Physicians around the world in the 1930s and 1940s failed to recognize the seriousness of elevated BP.

Even if the doctors taking care of Wilson, Roosevelt, and other national leaders, such as Stalin and Churchill, had recognized the dangers of hypertension, there was little treatment available prior to the 1940s. Malignant hypertension longevity was often measured in terms of months. Experimental treatments, like Walter Kempner's rice diet, lowered BP and prolonged life in severely ill patients but subjected them to a difficult lifestyle.2 Physicians around the world in the 1930s and 1940s failed to recognize the seriousness of elevated BP. Some believed that in older people, elevated BP was necessary to get blood to the brain. Others believed that people with high BP were psychoneurotic. A BP of anything below 200⁄100mm Hg was considered mild and benign.

Available treatments were dramatic, sometimes debilitating, and usually unsuccessful over the long term. Drs. Irvine Page and Edward Freis, pioneers in early treatment, induced high fevers in patients with malignant hypertension by using typhoid bacilli or malaria-related substances. High fevers with temperatures of up to 105˚F resulted in lower BPs as blood vessels dilated. Such primitive procedures were the only approaches available in the 1940s.

In the 1950s, the dangers of elevated BP were recognized by the Framingham Massachusetts Study and the Tecumseh Community Study, confirming that hypertension is a major cause of heart enlargement, heart failure, strokes, and kidney failure. Thereafter, research began on BP-lowering drugs like phenoxybenzamine and hexamethonium. Subsequently, hundreds of medications have been approved to lower BP.

In 1972, using social-science approaches, the National Institutes of Health launched the NHBPEP, bringing together numerous disciplines to advance efforts to lower BP in more people. The program set the national agenda for hypertension prevention and developed national guidelines for clinicians. Through the years, more than 2,000 community programs participated in the effort to raise awareness about the importance of detecting and treating hypertension.

Hypertension is the primary reason adults visit physicians.

In 1977, the NHBPEP released the first in a series of guidelines for the treatment of hypertension. Prior to this report, there had never been a national consensus recommendation for the evaluation and treatment of any disease. The increased visibility of hypertension as a public health problem resulted in an increase in the number of studies designed to determine best treatments for high BP. As a result, hypertension control rates continued to improve and mortality rates declined faster. The NHBPEP also identified racial and regional variations in hypertension control and stroke mortality in the US,3 then developed successful action plans to reduce disparities.

When the NHBPEP began, only a quarter of the public knew the relationship between high BP, stroke, and heart disease. Less than half of the population was aware their BP was elevated, less than a quarter was being treated, and only 10 percent had their BP controlled. A mass media campaign was developed, much of it performed as a public service by the media industry. Community health screening and educational interventions were initiated in churches, firehouses, and community events. Three decades later, more than 90 percent of the public is aware of the relationship between high BP, stroke, and heart disease. Every six months, three quarters of the population has their BP measured, and virtually every American has had their BP measured at least once.

The increase in awareness led to action. Hypertension is the primary reason adults visit physicians. Today, 81 percent of Americans are treated and half have their BP controlled. Age-adjusted mortality for heart disease and stroke has declined (70 percent and 80 percent, respectively), since the beginning of the program. Better awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension have contributed to these reductions. The declines are seen in both sexes and all races. The dramatic decreases in strokes and heart disease have occurred despite the substantial increase in obesity and diabetes in the US.

The program demonstrates that vision, cooperation, and commitment can result in major social, public health, and medical improvements.

While the NHBPEP succeeded in improving hypertension control and reducing death and disability from heart disease and stroke, it also met another important goal—demonstrating that a large federal effort to prevent, treat, and control a major disease can lead to ongoing, sustainable care even as the program is downsized. Patient education and treatment of hypertension are now part of routine medical care.

Large public health campaigns have emerged as lifestyle changes have been shown to prevent or slow the progressive rise in BP that occurs as people age.4 Recognition of low-salt diets are part of any prevention and treatment program for hypertension. Losing weight if overweight, moderating alcohol consumption, and increasing physical activity may also help lower BP and prevent or reduce the rate of rising arterial pressures. These actions are promoted by voluntary health agencies, public health departments, and professional societies. Despite the success in reducing cardiovascular disease, heart disease and stroke remain the first and third causes of death in the US. But death rates alone do not describe the burden of disease. In 2011, the total cost of cardiovascular disease in the US was estimated at $444 billion. Treatment of these diseases accounts for about $1 of every $6 spent on healthcare.5

It is likely that without the NHBPEP's efforts in promoting lifestyle changes and specific medical therapy to lower BP, several million more people would have died or suffered the disabilities of heart or kidney disease and stroke. The program demonstrates that vision, cooperation, and commitment can result in major social, public health, and medical improvements.

About the Author

Edward J. Roccella, MPH '69, PhD '77, worked for 30 years at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. He is the recipient of the NIH Director's Award and lifetime achievement awards from the International Society of Hypertension in Blacks and the American Society of Hypertension. Roccella recently received the Claude Lenfant Excellence Award for Population Hypertension Control from the World Hypertension League.

Marvin Moser (1924–2014) contributed to this article. Dr. Moser was senior medical advisor for the NHBPEP and published 500 peer-reviewed articles in medical and public health literature. He was the recipient of numerous awards and has been described as the ultimate public health activist for hypertension.

Notes

1. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48/12 (April 1999):241–43.

2. Hypertension 64 (2014):684–88

3. Lenfant, C., and Edward J. Roccella, "Regional and Racial Differences among Stroke

Victims in the United States," Clinical Cardiology 12/4 (1989):18–22.

4. Hyseni L., Elliot-Green A., Lloyd-Williams F., Kypridemos C., O'Flaherty M., McGill

R., et al. (2017) Systematic Review of Dietary Salt Reduction Policies: Evidence for

an Effectiveness Hierarchy? PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177535.

5. NHLBI 2012 Fact Book.

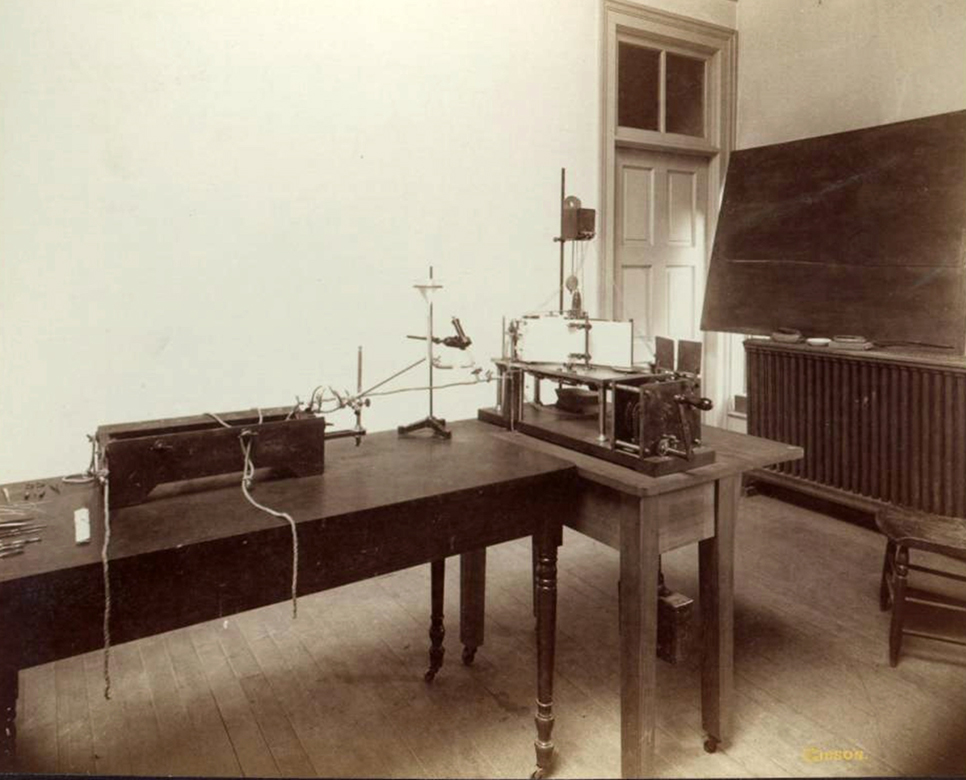

Photo Credits. Students practice taking blood pressure on the campus lawn, May 1958. University of Michigan News and Information Services Photographs. Bentley Historical Library © Regents of the University of Michigan; Blood Pressure, Innervation of Heart, Etc. by J. Jefferson Gibson, 1893. Bentley Historical Library; blood pressure machine at a dentist office in Washtenaw County.