“To Rid Society of Imbeciles”: The Impact of Dr. John Harvey Kellogg’s Stand for Eugenics

Elizabeth Stout

Master’s Student, Health Behavior and Health Education

When people think of eugenics, what most often comes to mind is Hitler’s persecution of Jews during World War II, but the American eugenics movement began significantly before, and served as a major inspiration. Modern eugenics emerged in the 1880s, with the goal of improving people’s genetic character by promoting reproduction by those with suitable characteristics and keeping those deemed unfit from reproducing, warning the unfit would otherwise bring down the entire world.

Experts at the time decided that the largest threat was “feeble minded” individuals, which included those with low intelligence, immoral behavioral habits, mental health conditions, and more. They supposedly were increasing in number rapidly, leading 12 states to pass sterilization laws by 1913.

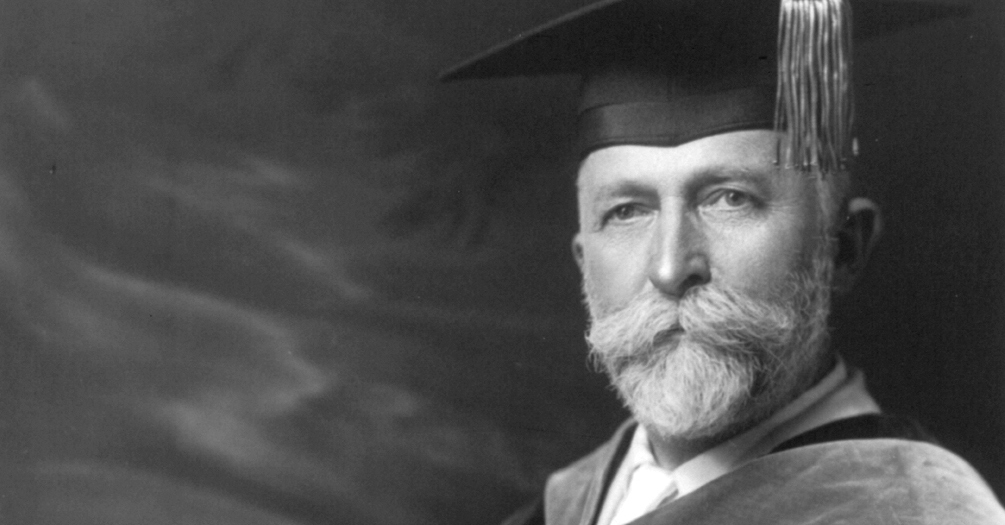

In Michigan, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg was a leader of the eugenics movement, perceiving it as the only way to save society from disaster. To promote this, Kellogg organized the First National Conference on Race Betterment, held from January 8-12, 1913, at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, which included more than 400 eugenics experts from across the country.

To encourage public involvement and support, the conference held “mental and physical perfection contests,” where children and babies were given tests and evaluations for rankings, with the winners receiving medals. The schedule was also published in newspapers, and thousands attended the conference.

The core of the conference was a presentation by Harry Laughlin titled “Calculations on the Working Out of a Proposed Program of Sterilization.” He claimed that 15 million sterilizations would be necessary to save the country, as the lowest ten percent of humans were so meagerly endowed that their reproduction constituted a social menace. Laughlin described specific strategies for effective programs, since current regulations were too weak.

To further inspire the public to take action on preventing the reproduction of the “feeble minded,” Kellogg wrote a paper titled “Needed – a New Human Race,” where he encouraged all people to become involved in eugenics. This included positive eugenics, where citizens deemed to have beneficial traits were encouraged to have large families.

Kellogg’s eugenics support impacted education in Michigan. Colleges began to offer or even require eugenics courses for students. Due largely to close proximity, Battle Creek College defined race betterment through eugenics as the primary and essential job of the college, and all students and staff were expected to support and promote it.

Michigan was the first state to propose eugenical sterilization in 1897, although the first sterilization law in the state did not pass until 1923. This law, upheld in court multiple times, led to 3,786 officially documented sterilizations. Seventy-six percent of these were on people deemed mentally deficient, 11% were people considered insane, and the other 13% were sexual deviants, people with epilepsy, or “moral degenerates.” African Americans and poor people were the main targets.

In the 1920s, selective breeding through eugenics became an American craze, based largely on the concept of race suicide. This theory posited that middle and upper class white people—the perceived superior race—were being outbred by all other races, and would die out if action was not taken.

In 1924 eugenics reached the Supreme Court with the case Buck v. Bell. Carrie Buck was the perfect subject, a member of a family with a large number of “feeble minded” individuals who had given birth out of wedlock. Almost all the evidence presented by the prosecution was false, and the defense did not make any effort to challenge the charges made; the goal of all parties involved was for a eugenical sterilization act to be passed. Virginia’s Ecumenical Sterilization Act was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court by a vote of 8-1. The decision relied heavily on Jacobson v. Massachusetts, a case ruling that children needed a smallpox vaccine, with claims that sterilization was a similar issue—it was necessary to protect the health of the country.

Carrie Buck became the first person sterilized in Virginia under the new law. Many states added or updated eugenic sterilization laws after the case, and by January 1935, 21,539 forced sterilizations had occurred across the country. Thirty-three states had statutes at some point in time that overall led to more than 60,000 involuntary sterilizations. The main force ending the movement in America was the association with Nazi Germany. Madison Grant, a prominent American eugenics supporter, even received a letter from Hitler, in which he proclaimed Grant’s book The Passing of the Great Race to be his bible. America did not want to be linked to the Nazis, so support for eugenics waned. However, the Buck v. Bell decision has never actually been overturned, and involuntary sterilizations still occur on rare instances, and they are perfectly legal. Understanding the history of eugenics in the United States is important, and can help us be more vigilant in ensuring that a similar movement does not start in the future.

Lead image: John Harvey Kellogg. , ca. 1914. July 17. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002715785/.

About the Author

Elizabeth Stout is a Master of Public Health student in the Health Behavior and Health

Education Department at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. She is

dedicated to providing support and acting as an advocate for people with disabilities,

which is promoted by her personal experience as a disabled individual. Outside of

college, she acts as a consultant for multiple health organizations, and enjoys spending

time surrounded by nature and playing piano.

Elizabeth Stout is a Master of Public Health student in the Health Behavior and Health

Education Department at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. She is

dedicated to providing support and acting as an advocate for people with disabilities,

which is promoted by her personal experience as a disabled individual. Outside of

college, she acts as a consultant for multiple health organizations, and enjoys spending

time surrounded by nature and playing piano.

- Read more about eugenics on the Pursuit.

- Learn more about Health Behavior and Health Education at Michigan Public Health.