Emergency Food Security Funding Must Continue

Alek Ostrander and Carly Truett

Master’s Students in Nutritional Sciences

COVID-19 can make people sick in ways beyond infection with the virus.

As the country responds to the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 26 million adults in the US are struggling to access and afford food.1 Federal nutrition assistance initiatives like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) have been proven to be effective and efficient at alleviating food insecurity and its related health impacts, as well as stimulating the economy.2,3 Modifications were granted to federal nutrition assistance programs to address the issue of growing food insecurity rates resulting from the pandemic.

Though modifications to SNAP—known as flexibilities—have been instrumental in reducing food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic, more could be done.

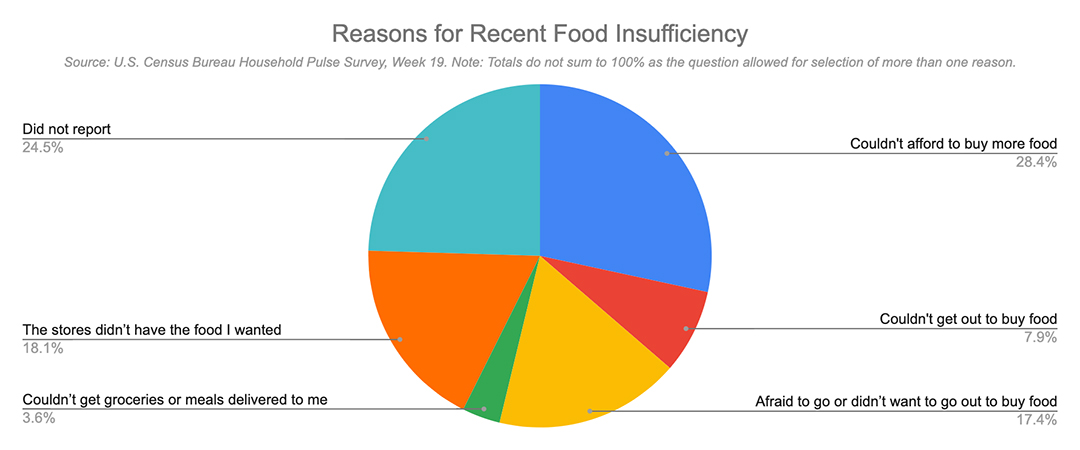

The recent rates of food insecurity in the US are significantly higher than the rates of food insecurity reported before the pandemic began. About 3.7% of adults reported that their household did not have enough to eat at some point over a span of 12 months in 2019, compared to 11.9% of adults in just the last week, from data collected November 11, 2020–November 23, 2020.4,1 Highlighted in figure 1, inability to afford food was the most commonly reported reason for food insufficiency. In households with children, 1 in 6 adults lacked food within the last 7 days.4

Figure 1. Reasons for Recent Food Insufficiency, from US Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Week 19.

To address the increase in food insecurity caused by COVID-19, legislators have created modifications to SNAP in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA). Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT)* was established to provide additional benefits to the 29.4 million children who receive free or reduced lunch and were no longer attending school in person.5 P-EBT has been extended from its original proposal in March until the end of the academic year in September 2021 USDA.6

The extension of P-EBT through September helps to aid families as schools transition between online and in-person learning during this school year. Even after the pandemic has resolved, providing P-EBT in the summer months should be considered as a way to mitigate food insecurity traditionally experienced by children in the summer.

Continuation of emergency allotments is dependent on individual states submitting monthly requests for extensions to the program.

Emergency allotments are an additional adjustment that allows households to receive the maximum SNAP benefits if they meet state-wide pandemic related conditions such as being from an area where businesses have closed or restricted their hours, living in a quarantine zone, or being from a state with an emergency declaration.7 Continuation of emergency allotments is dependent on individual states submitting monthly requests for extensions to the program.8

Emergency allotments help participants who were not previously receiving the maximum amount of SNAP benefits. However, they do nothing for the most vulnerable SNAP users who were already receiving the maximum benefit. Until the end of the pandemic, these at-risk participants should also receive an increase to their benefits.

In April, unemployment rates reached levels not seen since the Great Depression. The unemployment rate** is slowly decreasing from that April spike, but still sat at 6.9% in October.9 This does not include those who may have seen a reduction in work hours or who are sidelined from work.4 The ability to find and maintain employment will be precarious in the coming months as states continue to respond to the ongoing pandemic. In response to these challenges, the normal requirement that able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWD) work 20 hours per week is temporarily suspended.10 The ABAWD work requirement suspension will be in place until the emergency declaration of COVID-19 is lifted.11

The flexibilities added to SNAP in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have allowed us to examine how our federal nutrition assistance programming can be improved. Immediate additional assistance is needed for the most vulnerable SNAP users who were already receiving the maximum benefit. It is also imperative that policymakers examine how eliminating the ABAWD work requirement and expanding P-EBT may improve food security in our nation.

Notes

* P- EBT benefits distributes $250-$450 dollars per child that received free or reduced lunch to families via an electronic SNAP card.12

** Currently in the US, about 30 million people meet the official definition of unemployment or live with a family member who does.4

References

- Measuring Household Experiences during the Coronavirus Pandemic. US Census Bureau.

- Angell S, Forbes W, Beaudoin S. The Positive Effect of SNAP Benefits on Participants and Communities. Food Research and Action Center.

- Rosenbaum D, Dean S, Neuberger Z. The Case for Boosting SNAP Benefits in Next Major Economic Response Package. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- Tracking the COVID-19 Recession's Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- National School Lunch Program. Economic Research Service (USDA).

- Pandemic EBT–State Plans for School Year 2020-2021. Food and Nutrition Service (USDA).

- Agency Information Collection Activities: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Emergency Allotments (COVID-19). Federal Register.

- States Are Using Much-Needed Temporary Flexibility in SNAP to Respond to COVID-19 Challenges. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- The Employment Situation–October 2020. US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- SNAP–Families First Coronavirus Response Act and Impact on Time Limit for Able-Bodied Adults without Dependents (ABAWDs). Food and Nutrition Service USDA.

- SNAP COVID-19 Waivers. Food and Nutrition Service USDA.

- Lessons From Early Implementation of Pandemic-EBT. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

About the Authors

Alek Ostrander is a second-year master’s student in Nutritional Sciences at the University

of Michigan School of Public Health. She is interested in food access, nutrition policy,

and the social determinants of health. Ostrander works as a research assistant in

Cindy Leung’s lab and is vice president of the Nutritional Sciences Student Association.

Alek Ostrander is a second-year master’s student in Nutritional Sciences at the University

of Michigan School of Public Health. She is interested in food access, nutrition policy,

and the social determinants of health. Ostrander works as a research assistant in

Cindy Leung’s lab and is vice president of the Nutritional Sciences Student Association.

Carly Truett is a second-year master’s student in Nutritional Sciences at the University

of Michigan School of Public Health. She is the professional development and networking

chair of the Nutritional Sciences Student Association, works for the Ann Arbor YMCA,

and volunteers with the University of Michigan Student-Run Free Clinic. She is interested

in food access and security, health policy, and equity in health and nutrition.

Carly Truett is a second-year master’s student in Nutritional Sciences at the University

of Michigan School of Public Health. She is the professional development and networking

chair of the Nutritional Sciences Student Association, works for the Ann Arbor YMCA,

and volunteers with the University of Michigan Student-Run Free Clinic. She is interested

in food access and security, health policy, and equity in health and nutrition.