Leading with HEART: Working toward Health Equity with Anti-Racist Teaching

Melissa Creary, Paul Fleming, Sheeba Pawar, and Amel Omari

This year has put a spotlight on public health and the important ways the field must become explicitly anti-racist to advocate for institutional and systemic changes that will facilitate good health. When we invoke anti-racist principles, we're taking an active approach to the dismantling of structures and systems that were built within the context of prejudice and oppression. We are recognizing that racism lives within policies, attitudes, and perspectives that are ingrained in society and continue to marginalize people, and we must aim to change those structures. The same racism that leads to unfair outcomes for people of color in powerful institutions—like the criminal justice and educational systems—also underlies inequitable health outcomes disadvantaging Black and Brown populations in the US. COVID-19 has highlighted how structural racism is a root cause of the inequitable burden of illness and death on people of color.

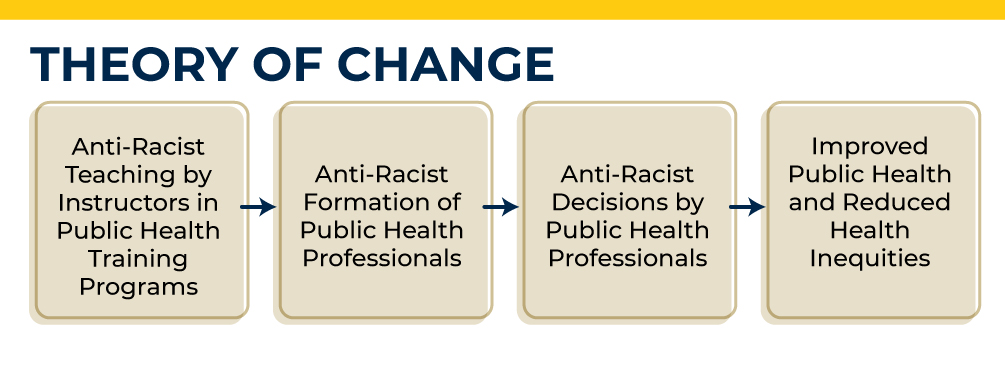

While some public health scholars have been proponents of anti-racism in the field for some time, the recognition of anti-racist practices in the health care field does not necessarily translate to recognition of implementing anti-racist teaching for people who train future public health professionals—such as faculty in public health degree programs. We believe that anti-racist teaching in public health training programs and investing in the education of public health students and trainees is critical to advancing health equity. When we educate students with anti-racist foundational practices, they can enter the professional world with these principles. This basis will inform their decisions and in-turn challenge inequitable practices and improve the public health for more people (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Theory of change toward equity for anti-racist pedagogical interventions.

Data collection, analysis, policy development, and program implementation are each general areas of public health learning competency. With training, instructors can help students understand how to implement these skills in explicitly anti-racist ways in their everyday practice as professionals. An instructional shift like this would have real benefits for public health practice once students graduate. For example, public health relies heavily on data collection and analysis to inform our policies. To work toward equity, public health professionals must learn how to collect inclusive and comprehensive data, seeking to remedy the bias we know exists in much of our currently available data. In turn, our future public health leaders must be prepared to act on the trends they observe, including by learning to incorporate anti-racist practices into policy and program development and implementation.

So what are the key principles of anti-racist teaching? Dr. Whitney Peoples, anti-racist teaching expert at the University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT), says anti-racist teaching means that we:

- Acknowledge racism in disciplinary, institutional, departmental contexts

- Center both structural and personal manifestations of racism

- Disrupt racism whenever and wherever it occurs

- Seek change within and beyond the classroom

- Bridge theory and practice

- Focus on the importance of process over time

Despite the importance of anti-racist teaching in public health, there isn’t much guidance on anti-racist teaching that is specific to our field. According to education expert Priya Kandaswamy, creating an anti-racist teaching approach requires helping students develop an analysis of power relationships at every level, from the interpersonal to the systemic.[7] For example, all public health instructors should feel capable in guiding students toward asking and seeking answers to the questions, “What power imbalances explain health inequities? And how do they do so?” Considering public health issues from this vantage point is crucial for shifting the entire field towards anti-racist principles, because gaining a deep understanding of how inequities happen will prepare future professionals to respond in ways that address the real causes of those inequities.

We have been on our own journeys towards anti-racist teaching. The faculty members on our team both started as assistant professors in Fall 2016 and leaned on each other and other colleagues to improve our teaching and learn more about anti-racist teaching principles. Like many of our colleagues, we are constantly investing in our own development as anti-racist instructors, and consider this work a commitment to being learners over the entirety of our careers. We strongly believe that anti-racist teaching is crucial for the field of public health and that there is a great need for more support for public health instructors—including ourselves—who want to move towards anti-racist teaching.

Anti-racist teaching is not a specific skill set but rather a lifelong commitment to following anti-racist teaching principles, committing to a reflective teaching practice, and disrupting power hierarchies. We wish to suggest that anti-racist teaching need not be the academic expertise of every professor, but that every professor should commit to the journey toward anti-racist instruction.

With generous support from the University of Michigan School of Public Health Dean’s Office and the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions initiative, we have initiated Project HEART (Health Equity via Anti-Racist Teaching) to create publicly available resources to train public health instructors on anti-racist teaching. The project was borne out of our desire to help others like us on this journey.

We won’t get everything right, but we know we have to start somewhere. Both the HEART Collaborative, our online community, and the massive open online course (MOOC) that will come out of it, are products of the public health we need. These resources will help us and others continue to better understand and apply anti-racist teaching principles for public health. Recent critiques have highlighted how public health institutions are falling short of our mission to assure the health of all populations. Guiterrez’ Performance of “Antiracism” Curricula, rightfully calls out new lip service to the commitment of racism as a public health issue. We aim to close the distance between what public health institutions say publicly about commitments to anti-racism and what they actually are doing. Institutions of higher education, including our own, have been criticized for either a failed response, delayed response, or lack of response to the onslaught of racial injustices in our society. Our classrooms are embedded in an unjust society and our instructors must be better trained to address those injustices. In a field where, at our core, we are positioned to fight against inequities, the public health classroom demands anti-racist teaching.

Follow the HEART Collaborative on Twitter for share resources and reflections on the team’s journey of growth toward anti-racist public health teaching.