A broader, more inclusive look at childhood health: The child-serving ecosystem.

Alison Miller

Professor of Health Behavior and Health Education

Early childhood (prior to age 5 years) is characterized not only by rapid physical growth and brain development, but also by social and emotional development in the context of trusting relationships, specifically with caregivers. A young child’s health and development is shaped by the relationship they share with their caregivers, and in turn by individuals within a larger set of societal and environmental contexts that make up a broad child-serving ecosystem. “Early relational health” between children and caregivers is a concept increasingly recognized as foundational for shaping mental and physical health and well-being during early childhood and beyond (Willis & Eddy, 2022). Extending the notion of relational health across the child-serving ecosystem may help promote child well-being on a broad scale by connecting individuals across the many systems and sectors that impact child health and development (Miller et al. 2022).

Unfortunately, many young children in the United States and globally experience poverty, racism, violence, abuse, neglect and other interpersonal stressors or traumatic events that can harm development. When exposures to adverse childhood experiences (or ACEs) happen during early life, they can result in toxic levels of stress and over time may lead to chronic health outcomes, mental illness, and substance misuse in adulthood through biological and behaviorally-mediated pathways. Such conditions also have implications for intergenerational transmission of the impacts of trauma and adversity exposures, influencing public health over the long term (Hughes et al., 2017).

Luckily, early relational health can buffer the impacts of early adversity and trauma (Willis & Eddy, 2022). By establishing safe, trusting, and stable relationships with caregivers, a child can build resilience to support recovery from early experiences of adversity. Indeed, “nurturing care” interventions that seek to promote relational health between child and caregiver(s) are a key focus of global efforts to enhance child health and development on a broad scale (Britto et al. 2016).

The relationship between a young child and that child’s main caregiver(s)—often, but not always, a child’s parent—is considered the “primary relationship” as it is typically the first and most impactful. The primary relationship is established during infancy, a period of development when children are learning critical information about the world around them. The primary relationship ideally serves as a secure base from which the child can explore the world, and a safe haven to return to when things get tough.

Caring for the needs of a young child can be physically, emotionally, and financially challenging. Thus, for caregivers to best support young children, it is important for them to also be supported. Caregivers living with adversity can face situations that place stress on the primary relationship, making it difficult to care for young children. For example, poverty, the COVID-19 pandemic, and caregivers’ own experiences of trauma can interfere with their capacities to meet their child’s needs (Masten, 2022). Although support services exist, these are often disconnected and can be difficult to access. Furthermore, many of these burdens fall disproportionately on families who have historically faced structural challenges such as intergenerational poverty, under-resourced communities, and systemic racism.

This is why we must consider a broader view of who makes up the Child-Serving Ecosystem, and the relational health among individuals in the ecosystem.

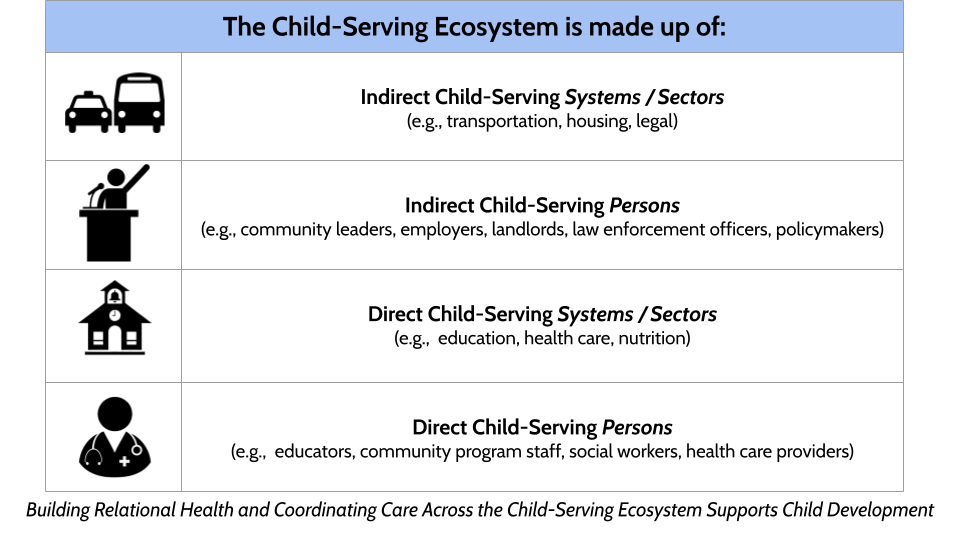

Beyond the primary relationship, a young child’s health and development is shaped

by a larger set of social and ecological contexts in which both child and caregiver

are nested (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). These contexts make up a child-serving

ecosystem that includes a range of systems, sectors, and individuals, including public

health practitioners, who serve the needs of children both directly and indirectly

(Miller et al 2022). For example, direct child-serving persons can include educators,

social workers, and health care providers and indirect child-serving persons can include

community leaders, landlords, and policymakers. Across the child-serving ecosystem,

services are often fragmented and efforts to coordinate them take significant time

and energy, with burdens falling on primary caregivers or direct service providers.

Using a relational health framework to re-imagine coordination of care across the

child-serving ecosystem can improve public health by better supporting caregivers

and broadly promoting child health and development.

Beyond the primary relationship, a young child’s health and development is shaped

by a larger set of social and ecological contexts in which both child and caregiver

are nested (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). These contexts make up a child-serving

ecosystem that includes a range of systems, sectors, and individuals, including public

health practitioners, who serve the needs of children both directly and indirectly

(Miller et al 2022). For example, direct child-serving persons can include educators,

social workers, and health care providers and indirect child-serving persons can include

community leaders, landlords, and policymakers. Across the child-serving ecosystem,

services are often fragmented and efforts to coordinate them take significant time

and energy, with burdens falling on primary caregivers or direct service providers.

Using a relational health framework to re-imagine coordination of care across the

child-serving ecosystem can improve public health by better supporting caregivers

and broadly promoting child health and development.

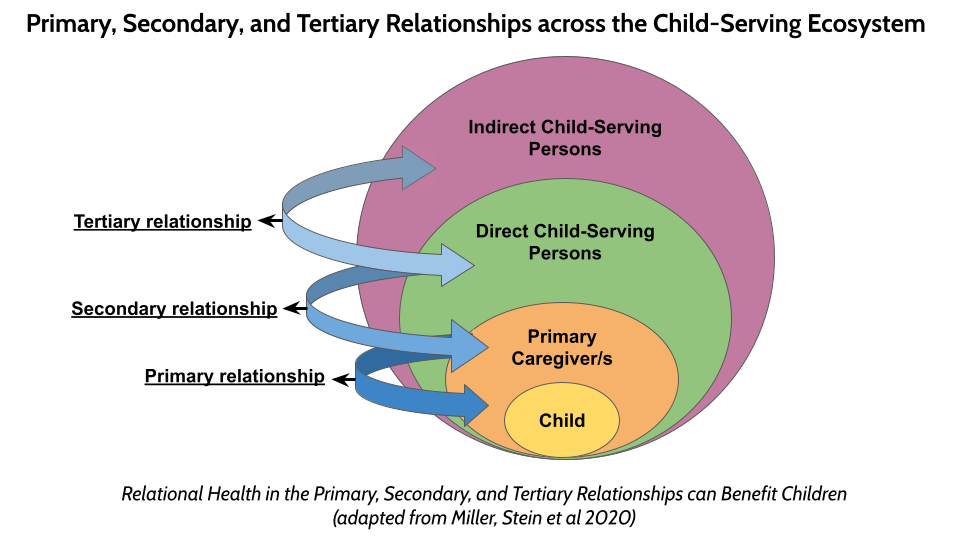

We recently proposed a model of relational health across the child-serving ecosystem

(Miller et al 2022). Three key relationships are illustrated below. Beyond the primary caregiver-child relationship, the “secondary relationship” reflects

connections between caregivers and direct child service providers.  A trusting secondary relationship can benefit the child as caregivers may be more

likely to enact recommendations when they feel seen and heard by trusted providers.

For example, the health of the secondary relationship can influence whether screening

families for social needs in pediatric clinics is helpful or whether it results in

stigma (Sokol et al., 2021). “Tertiary relationships” reflect connections between

direct-service providers and individuals working in systems and sectors who don’t

serve children directly, and among individuals in sectors that indirectly serve child

needs. The health of these tertiary relationships can help smooth cross-system, cross-sector

interactions. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring that children could

receive food when schools were closed required coordination of individuals across

education and nutrition policy sectors. We also saw examples of indirect child service

providers like food bank workers and landlords working together to support families.

Recognizing the value of and need for relational health at multiple levels may be

a way to facilitate effective collaboration among individuals across the child-serving

ecosystem and establish a coordinated web of support for child health and development.

A trusting secondary relationship can benefit the child as caregivers may be more

likely to enact recommendations when they feel seen and heard by trusted providers.

For example, the health of the secondary relationship can influence whether screening

families for social needs in pediatric clinics is helpful or whether it results in

stigma (Sokol et al., 2021). “Tertiary relationships” reflect connections between

direct-service providers and individuals working in systems and sectors who don’t

serve children directly, and among individuals in sectors that indirectly serve child

needs. The health of these tertiary relationships can help smooth cross-system, cross-sector

interactions. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring that children could

receive food when schools were closed required coordination of individuals across

education and nutrition policy sectors. We also saw examples of indirect child service

providers like food bank workers and landlords working together to support families.

Recognizing the value of and need for relational health at multiple levels may be

a way to facilitate effective collaboration among individuals across the child-serving

ecosystem and establish a coordinated web of support for child health and development.

Strategies to build cross-system, cross-sector relational health across the broad child-serving ecosystem include promoting interdisciplinary education around the importance of multi-level relational health for early child development, and providing early-career interprofessional education opportunities to connect and collaborate (Miller et al 2022). As children cannot advocate for themselves, it is up to us to develop and support the many systems that promote their well-being. Coordinating care and services that are developmentally-informed and child- and family-centered will benefit children both during their childhood years and forward into adulthood.

Sara Stein, LMSW; Rebeccah Sokol, PhD, MSPH; Phoebe Trout, MPH, MPP; Christopher Giang also contributed to this article.

References:

Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, Yousafzai AK, Matthews SG, Vaivada T, Perez-Escamilla R, Rao N, Ip P, Fernald LC, & MacMillan H. (2016). Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. The Lancet, 389(10064):91-102.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 993–1028). New York, NY: Wiley.

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, & Dunne MP. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health;2(8):e356-66.

Masten, A. (2022, June). Protecting children from the pandemic’s impacts requires that we support their parents. Child and Family Blog. https://childandfamilyblog.com/challenges-covid-19-for-caregivers-and-community/

Miller, A. L., Stein, S. F., Sokol, R., Varisco, R., Trout, P., Julian, M. M., Ribaudo, J., Kay, J., Pilkauskas, N. V., Gardner-Neblett, N., Herrenkohl, T. I., Zivin, K., Muzik, M., & Rosenblum, K. L. (2022). From zero to thrive: A model of cross-system and cross-sector relational health to promote early childhood development across the child-serving ecosystem. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43, 624– 637. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21996

Sokol, R.L., Ammer, J., Stein, S.F., Trout, P., Mohammed, L. and Miller, A.L. (2021). Provider Perspectives on Screening for Social Determinants of Health in Pediatric Settings: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 35(6), pp.577-586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.08.004

Willis, D. W., & Eddy, J. M. (2022). Early relational health: Innovations in child health for promotion, screening, and research. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43, 361– 372. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21980

About the Author

Dr. Alison Miller is a developmental psychologist and Professor of Health Behavior

and Health Education based in the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan.

She is an expert in early childhood development and studies individual child, family,

and social-contextual factors as influences on child health and well-being. She has

conducted research on early-life stress and child self-regulation in relation to mental

health, eating behavior and obesity, sleep, media use, and physical activity, with

a focus on how parenting and social determinants of health also shape child functioning

in these areas. A goal of her work is to apply developmental science perspectives

and findings to inform community-, school- and/or family-based interventions seeking

to promote child development and well-being and reduce health inequities. alisonmillerlab.com

Dr. Alison Miller is a developmental psychologist and Professor of Health Behavior

and Health Education based in the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan.

She is an expert in early childhood development and studies individual child, family,

and social-contextual factors as influences on child health and well-being. She has

conducted research on early-life stress and child self-regulation in relation to mental

health, eating behavior and obesity, sleep, media use, and physical activity, with

a focus on how parenting and social determinants of health also shape child functioning

in these areas. A goal of her work is to apply developmental science perspectives

and findings to inform community-, school- and/or family-based interventions seeking

to promote child development and well-being and reduce health inequities. alisonmillerlab.com

- Learn more about Health Behavior and Health Education at Michigan Public Health.

- Read more on the Pursuit.