Detroit’s legacy of housing inequity has caused long-term health impacts − these policies can help mitigate that harm

By Roshanak Mehdipanah, Kate Brantley, and Melika Belhaj

This article was originally posted on The Conversation.

![]()

Detroiters who face rising rents, poor living conditions and systemic barriers to affordable and safe housing are at greater risk of poor health, our research finds.

We study the connection between housing inequities and health, with the goal of informing local, state and national policy. Our focus is on how interdisciplinary research on housing relates to equity in health, race, income and aging.

Housing instability can take many forms, including living in overcrowded or inadequate conditions, having to make frequent moves or spending the bulk of household income on a place to live. These stressors can lead to an increased risk of eviction, homelessness, poor mental health and even physical illness.

Half of Detroit’s residents are renters who earn a median household income of $26,704, nearly $13,000 lower than Michigan’s median, according to American Community Survey data.

We also found that 60% of renters in Detroit are cost-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing-related costs, including rent and utilities.

A legacy of discriminatory housing practices

These issues didn’t develop overnight. Detroit’s current racial housing inequities are influenced by the legacy of redlining. Redlining refers to the federally sponsored practice of banks and insurers refusing or limiting loans, mortgages and insurance within Black neighborhoods.

The effects were long term. As recently as 2019, formerly redlined areas had almost 30% lower homeownership rates and a $60,000 difference in median household income compared with mostly white areas that were provided with better opportunities beginning nearly a century ago.

Beyond the financial effects, research also shows that the practice of redlining in Detroit is associated with self-reported poor health, heart disease and poor vision among current residents of these areas.

Tax foreclosure leads to poor health outcomes

Discriminatory housing practices continue today, often taking the form of foreclosures and evictions.

In the past two decades, Detroit has experienced one of the highest tax foreclosure rates in the country.

At the height of the foreclosure crisis in 2015, approximately 6,408 owner-occupied homes were repossessed by banks, displacing those Detroiters and putting them at a higher risk of poor mental health.

This has led to more sales at auction to investors and speculators, who tend to evict more tenants than other types of landlords and to allow their properties to fall into disrepair.

Eviction, poor housing quality and health

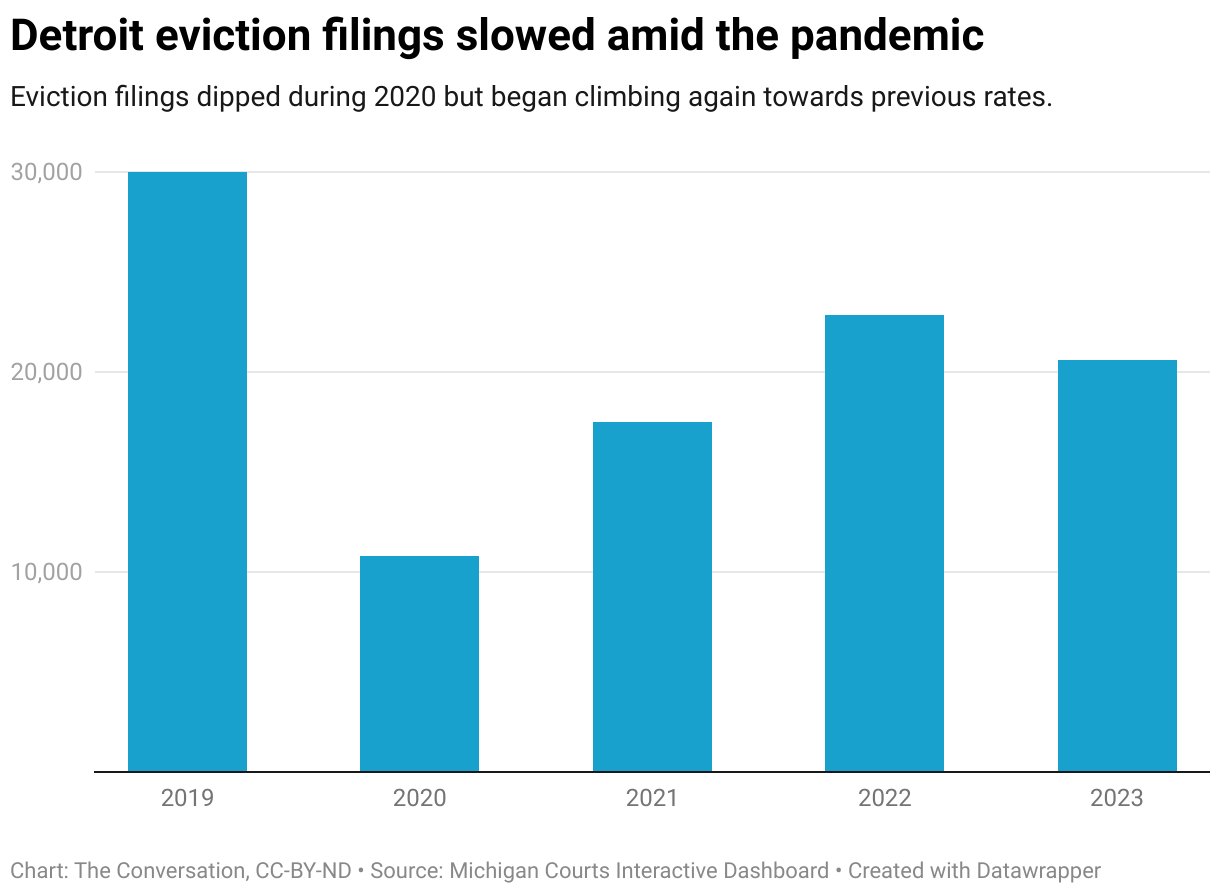

Detroit saw about 30,000 eviction filings annually before the COVID-19 pandemic.

After a few years of respite due to pandemic-era housing policies, evictions have climbed back toward prepandemic levels. In 2023, more than 20,000 Detroiters had evictions filed against them.

Research connects eviction to a range of poor physical and mental health outcomes.

Even the Detroiters not at risk of eviction often pay increasing rental costs for poor-quality housing despite attempts by the city to implement a rental ordinance requiring landlords to register and obtain a certification of compliance with Detroit’s rental ordinance.

Research shows that 9 in 10 pandemic-era eviction filings involved properties not in compliance with local health and safety codes, including those that regulate lead hazards. At the same time, much of the housing stock continues to decline as it ages and compliance efforts are not well enforced.

Some who are evicted have nowhere to go. In January 2023, 1,691 Detroiters were experiencing homelessness, increasing their risk of mental health challenges, disease and even death.

Policies that have worked

There is some good news. Tax foreclosures in Detroit have decreased significantly from the height of the tax foreclosure crisis.

We partly attributed this to the pandemic-era moratorium on tax foreclosures initiated by the Wayne County Treasurer’s Office, which ended in 2023. The county also oversees the Michigan Homeowner Assistance Fund and programs such as Pay As You Stay and the Detroit Tax Relief Fund, which have helped clear tax debt for homeowners.

Programs such as Detroit’s Homeowners Property Exemption program have exempted some low-income homeowners from paying property taxes in an effort to prevent tax delinquency.

However, our research shows that despite efforts to raise awareness about these programs, few qualifying households access them. This places them at risk for foreclosure and possible displacement.

New policy directions

Detroiters’ resilience and persistent advocacy have led to significant wins for housing justice, helping to translate community concerns into city policy.

In 2022, residents successfully organized for the right to counsel for qualifying low-income Detroiters facing eviction.

The city could also follow the lead of other U.S. cities such as Philadelphia by exploring eviction diversion and mediation models to reduce eviction filings.

More targeted efforts are also needed to invest in Black homeownership to ensure stability and encourage long-term residence.

About the Authors

Roshanak Mehdipanah is an associate professor of Health Behavior and Health Education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Mehdipanah is the co-lead for the Public Health IDEAS for Creating Healthy and Equitable Cities and the director of the Housing Solutions For Health Equity initiative.

Kate Brantley is a research area specialist at Housing Solutions for Health Equity at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Melika Belhaj is a research associate and program manager at Housing Solutions for Health Equity at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.