A Nudge Is Better Than a Shove

Tiffany Yang

A GPS guides you in the right direction to your destination. Your car beeps if you set off without putting your seatbelt on. Your new employer automatically enrolls you into a retirement plan. Your printer defaults to double-sided printing.

These are all example of nudges--reminders, warnings, policies, and feedback--that are designed to shift us toward making better lifestyle choices. These little nudges provide cognitive and environmental structures that makes certain choices easier.

They are meant to be simple and transparent, while maintaining freedom of choice. You don't have to follow the route set by your GPS; your car doesn't stop moving just because you haven't put your seatbelt on; you can opt out of your retirement plan; and you can select single-sided printing.

Instead, what these nudges do is help you default to making faster and safer journeys, saving for your retirement, and wasting less paper.

A common type of health nudge comes from the government in the form of health warnings or messaging such as educational campaigns aimed at reducing childhood obesity by providing parents with information on how to make healthier choices for their children. This is an information-based nudge in which education is provided to facilitate change.

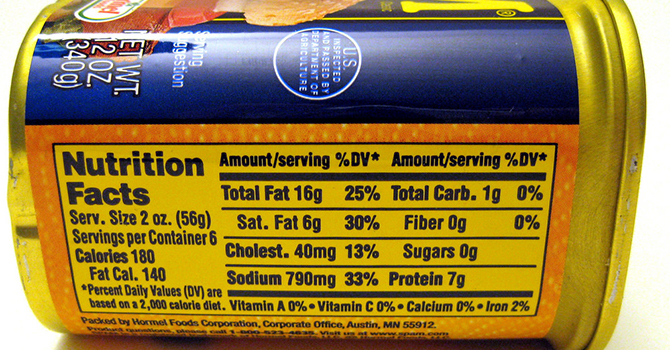

Other types of nudges may take the form of government mandates such as nutrition labelling on packaged foods or at fast food restaurants, or changes in the social environment that alter the availability of choices, such as rules about product placement in grocery stores by the checkout counters.

Nudges don't have to take a top-down approach. Many behavioral scientists are studying how we can or do alter our environment to provide our own nudges. While there is always a great deal of interest in diet and physical activity, government informational campaigns encouraging people to eat a healthy diet don't always translate into practical tips and outcomes for individuals, as they rely on individuals to take the information and apply it to their lives.

Instead, scientists are investigating whether there are ways for people to "hack" their environment in order to influence how they perceive what they eat. For example, dinner plates with wider or colored rims lead diners to overestimate the amount of food presented; this illusion could be used as a visual nudge by individuals who wish to feel satisfied on smaller portions of food.

Similarly, eating while distracted leads to an increase in the amount of food consumed not only during the distraction, but also later on. Being present while you are eating increases awareness of how much you ate and feelings of fullness. It also increases your ability to effectively recall what you consumed earlier as a way to gauge how hungry you may be at a later meal.

Recent work in Europe has found the use of health nudges to be supported by the majority of the population as they are viewed as helpful, rather than deceptive. There is still a lot of research to be done in how we are influenced by our surroundings, and it is possible that small nudges in behavior may end up being a more sustainable and acceptable public health strategy to create environments that help us make better choices.

References

- Reisch, Lucia A., Cass R. Sunstein, and Wencke Gwozdz. "Beyond carrots and sticks: Europeans support health nudges." Food Policy 69 (2017): 1-10.

- Sunstein, Cass R. "Nudging: a very short guide." Journal of Consumer Policy 37.4 (2014): 583-588.

- McClain, Arianna, et al. "Visual illusions and plate design: the effects of plate rim widths and rim coloring on perceived food portion size." International journal of obesity (2005) 38.5 (2014): 657.

- Robinson, Eric, et al. "Eating attentively: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of food intake memory and awareness on eating." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2013): ajcn-045245.

- Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. "Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness." (2008). Yale University Press.

About the Author

Tiffany Yang, PhD, MPH, RD, is a 2014 graduate of the Nutritional Sciences program at the University of

Michigan School of Public Health. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the

Bradford Institute for Health Research in Bradford, UK, where she works with the Born

in Bradford cohort to examine early life stressors on childhood health and well-being.

In her free time she enjoys reading, local beers, making a mess in the kitchen, and

exploring.

Tiffany Yang, PhD, MPH, RD, is a 2014 graduate of the Nutritional Sciences program at the University of

Michigan School of Public Health. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the

Bradford Institute for Health Research in Bradford, UK, where she works with the Born

in Bradford cohort to examine early life stressors on childhood health and well-being.

In her free time she enjoys reading, local beers, making a mess in the kitchen, and

exploring.