Making Family Planning a Household Name: The Legacy of Title X

Chloe Bakst

Bachelor’s Student in Public Health

Fifty years ago, Title X was created as a popular, bipartisan public health measure. At the center of Title X is family planning—the idea that children and families generally are healthier when parents have some say in the number and spacing of children, including the decision not to have children.

Progress in family planning is considered by the Centers for Disease Control as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century.[1] Improved family planning, such as increased access to counselling and contraception, not only prevents unintended pregnancies but also contributes to healthier outcomes for mothers and babies.[2]

A Question of Health Equity

Nearly 4 million women in the US depend on clinics supported by Title X of the Public Health Service Act for family planning, contraception, and other reproductive health services. Title X patients are disproportionately young, poor, and of color.[3] In the state of Michigan, 54% of Title X patients are below the federal poverty level.[4]

Recently proposed rule changes to the Title X program[5] would deny funding to clinics that “indirectly facilitate, promote, or encourage abortion in any way.”[6] In order to understand the full effect of these proposed changes, it is necessary to understand the impact of Title X on public health.

A Very Brief History of Title X

In 1969, President Nixon expressed his belief that regardless of economic status every

person in need of family planning should be able to access such services. In 1970,

then-US Representative George H. W. Bush championed Title X of the Public Health Service

Act, the only federally funded family planning program.[7] There was little political opposition at the time. The measure passed 298–32 in the

House and unanimously in the Senate. Title X was framed as an effort to improve the

public health of the nation.

In 1969, President Nixon expressed his belief that regardless of economic status every

person in need of family planning should be able to access such services. In 1970,

then-US Representative George H. W. Bush championed Title X of the Public Health Service

Act, the only federally funded family planning program.[7] There was little political opposition at the time. The measure passed 298–32 in the

House and unanimously in the Senate. Title X was framed as an effort to improve the

public health of the nation.

Currently, more than 4,500 federally qualified and other health clinics rely on Title X funding, including 90 in the state of Michigan.[8] Title X provides for a diverse array of clinic expenses, including medical care like contraception, training for nurses and other care providers, and systematic data collection.[9] Importantly, clinics are legally prohibited from using Title X funds for costs related to abortion services.

Billions of Dollars in Savings

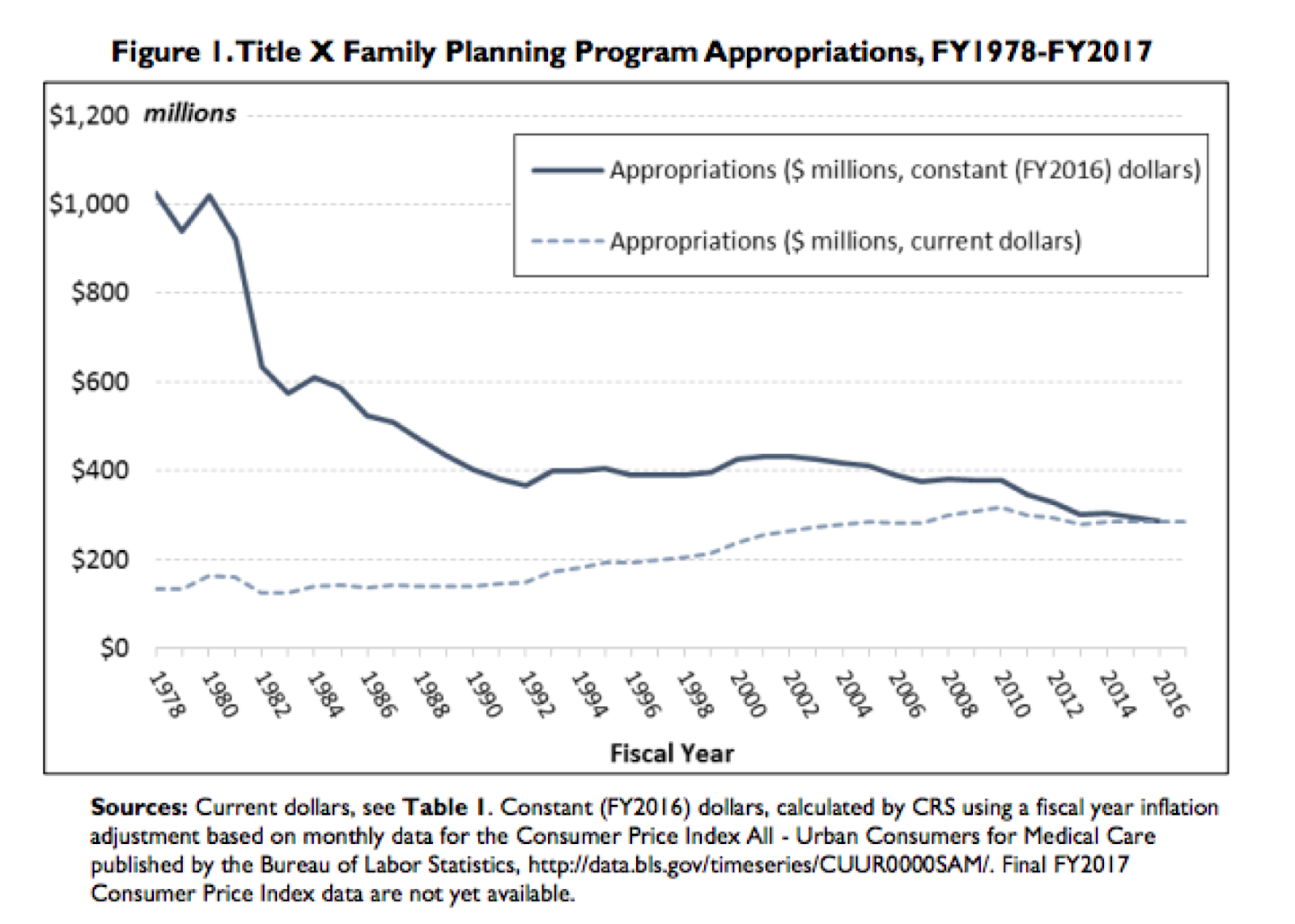

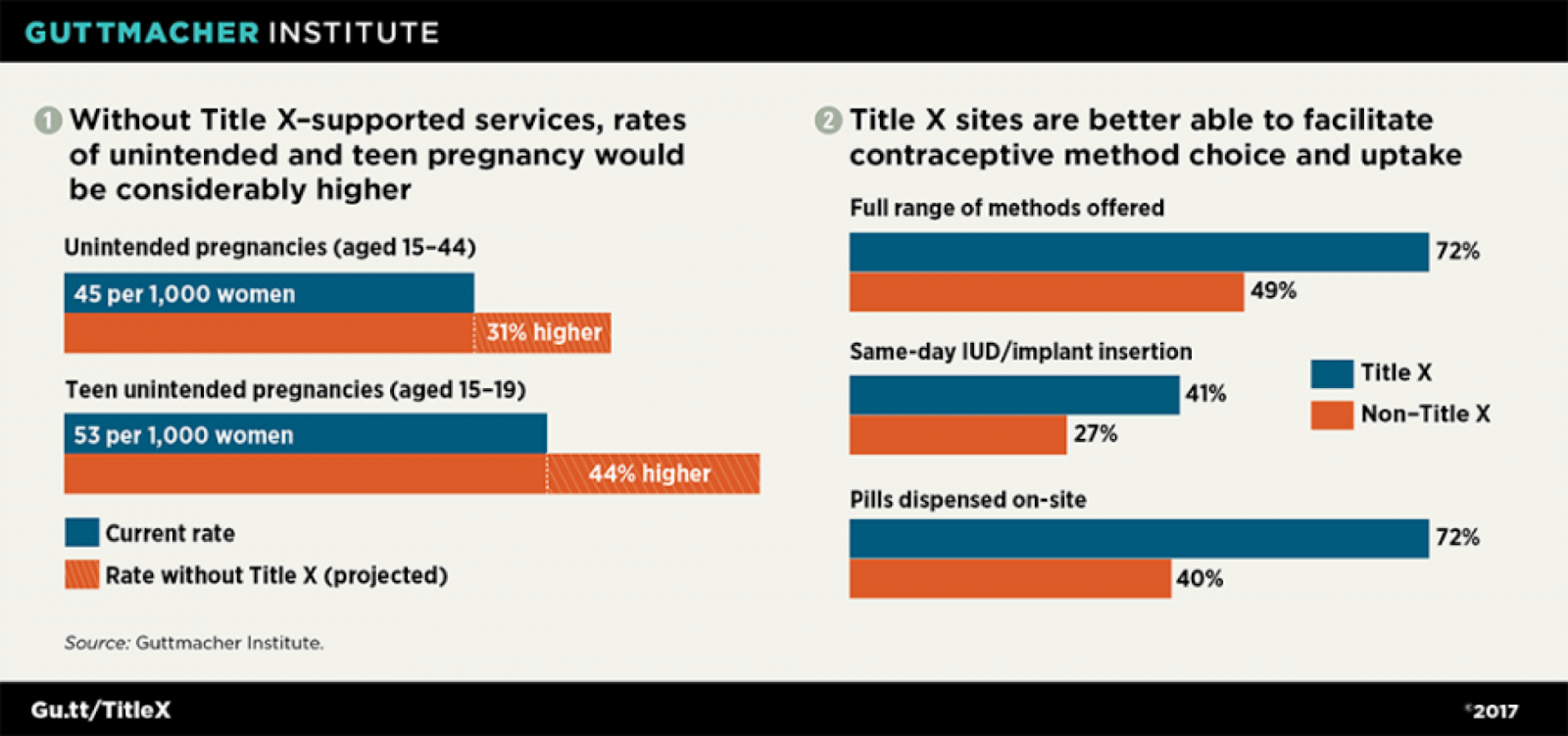

Despite such comprehensive coverage and a shrinking budget (see graph A), Title X still manages to save states and the nation as a whole millions of dollars. In 2010, an estimated $5.3 billion dollars of public money was saved by services at Title X supported clinics.[10] Beyond dollars and cents, the family planning services provided by these clinics means that 1.2 million unintended pregnancies were prevented. If Title X clinics did not perform these services, the unintended pregnancy rate in the US would be 35% higher in general and 42% higher for teenagers specifically.[11]

Studies have found that Title X clinics provide comprehensive, high-quality care to their patients (see graphic B).[12] Federally qualified health clinics that receive Title X funding provide a wider range of contraceptive options than those that do not receive such funding, with an average of almost 10 choices.[13] Nearly 7 in 10 Title X-funded health clinics that are federally qualified offer at least one form of long-acting reversible contraception, such as IUDs, which provide 99.99% protection from pregnancy.[14]

|

|

The 2010 Title X budget, in constant dollars, is 62% of the budget in 1980. |

A Public Health Legacy under Threat?

The Trump administration’s proposed changes to Title X would deny funding to clinics that even imply abortion exists as a family planning option, despite the fact that Title X funds were not and are not allowed to cover abortion related costs.[3] This puts clinics in a precarious position: they either cease providing the comprehensive, high-quality care that is the legacy of Title X, or they lose a significant portion of their federal funding and may have to close.

If family planning is anything, it is a public health matter.

—George H. W. Bush

In a recent Lancet article, Jody Steinauer and Philip Darneya of UC-San Francisco’s Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health argue that using federal funding to regulate provider-patient communication violates the ethics code of the American Medical Association.[3] But if clinics refuse to limit open, honest communication between provider and patient, lose funding, and have to close, many of the 4 million women who rely on Title X-supported clinics will likely be left without care.

|

| Title X clinics provide comprehensive care. |

Title X has been consistently successful, despite a shrinking budget. Title X clinics provide comprehensive care that helps prevent unintended pregnancies and promote safe, healthy births. Title X patients are socially and economically vulnerable, relying on these clinics as perhaps their only access to healthcare.

Using Title X as a political weapon or a wedge issue goes against the popular, bipartisan population health measure its original proponents intended it to be. As George H. W. Bush said in 1969 [15], “We need to make population and family planning household words. . . . If family planning is anything, it is a public health matter.”

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: family planning. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:1073–80

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: family planning. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:1073–80

- Steinauer, J., & Darney, P. (2018). Proposed changes to the Title X Family Planning Program. The Lancet, 392(10145), e6.

- National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association. (2018). The Title X Family Planning Program in Michigan.

- Janiak, E., O’Donnell, J., & Holt, K. (2018). Proposed Title X Regulatory Changes: Silencing Health Care Providers and Undermining Quality of Care. Women’s Health Issues, 28(6), 477–479. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2018.08.003

- Steinauer, J., & Darney, P. (2018). Proposed changes to the Title X Family Planning Program. The Lancet, 392(10145), e6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31733-1

- Coleman, C., & Jones, K. P. (2011). Title X : A Proud Past, an Uncertain Future. Contraception, 84(3), 209–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2011.05.014

- National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association. (2018). The Title X Family Planning Program in Michigan.

- Coleman, C., & Jones, K. P. (2011). Title X : A Proud Past, an Uncertain Future. Contraception, 84(3), 209–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2011.05.014

- Gold, R. B., Hasstedt, K., & Frost, J. J. (2014). Title X: a critical difference. Contraception, 89(2), 71–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.005

- Gold, R. B., Hasstedt, K., & Frost, J. J. (2014). Title X: a critical difference. Contraception, 89(2), 71–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.005

- Gold, R. B., Hasstedt, K., & Frost, J. J. (2014). Title X: a critical difference. Contraception, 89(2), 71–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.005

- Gold, R. B., Hasstedt, K., & Frost, J. J. (2014). Title X: a critical difference. Contraception, 89(2), 71–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.005

- Gold, R. B., Hasstedt, K., & Frost, J. J. (2014). Title X: a critical difference. Contraception, 89(2), 71–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.005

- George H.W. Bush (TX). (1969). “MANY MEMBERS FAVOR A MORE ACTIVE PROGRAM IN POPULATION AND FAMILY PLANNING” Congressional Record 115, p4207.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Chloe Bakst is a senior graduating in May 2019 with a Bachelor of Arts in Public Health

and a minor in Gender and Health. She is passionate about the intersection of health,

policy, and equity. After graduation, Chloe will pursue a career in Washington, DC,

in the field of maternal and reproductive health.

Chloe Bakst is a senior graduating in May 2019 with a Bachelor of Arts in Public Health

and a minor in Gender and Health. She is passionate about the intersection of health,

policy, and equity. After graduation, Chloe will pursue a career in Washington, DC,

in the field of maternal and reproductive health.