A COVID-19 Vaccine Needs the Public’s Trust—And It’s Risky to Cut Corners on Clinical Trials, as Russia Is

Abram L. Wagner

Research Assistant Professor of Epidemiology

This article was originally posted on The Conversation.

![]()

Russia’s announcement that a fast-tracked COVID-19 vaccine is registered there—with plans for quick distribution in the general population this fall—is being condemned by scientists worldwide.

Findings from scientific studies of this vaccine, named “Sputnik V,” are not available. Large safety and efficacy trials are only now getting underway. But despite only two months of preliminary testing in people, Russian President Vladimir Putin called the vaccine “quite effective,” and it has received regulatory approval.

In other places, notably the United States, China, and the European Union, even as researchers rush to develop vaccines, they continue to publish studies of these vaccines at a more measured pace than is happening in Russia.

The medical research system must make sure any vaccine is safe and effective before distributing it to the population at large.

As an epidemiologist who studies vaccine hesitancy and vaccine-preventable disease, I’m concerned about this news from Russia. After essential workers and high-risk groups are vaccinated, I would want to be among the first in line for an approved COVID-19 vaccine, but the medical research system must make sure any vaccine is safe and effective before distributing it to the population at large.

Clinical Trials Have a Valuable Role

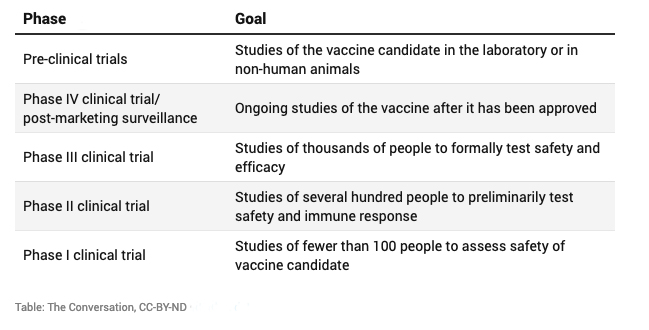

Before any drug, vaccine, or medical device is licensed for use in the general population, it needs to go through several rounds of large-scale testing. These studies are designed to make sure the intervention is safe and effective and to understand what the appropriate dosage will be.

What happens in each phase of clinical trials?

Under normal conditions, the research required to bring a vaccine to market can take decades. For example, before the HPV vaccine was licensed in the US in 2006, a phase III clinical trial enrolled 18,644 participants in 2004-2005, a phase II clinical trial had enrolled 1,113 participants in 2000, and the laboratory studies that led to a vaccine candidate had been published in the early 1990s.

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, scientists around the globe are focusing their efforts on developing a COVID-19 vaccine. They’re working at an unprecedented pace to move through the necessary clinical trials to end up with a safe and effective vaccine. One of the most time-consuming parts of clinical trials is enrolling participants, and pharmaceutical companies have sped up this process by lining up volunteers early, obtaining important baseline data from them even before a vaccine candidate is available.

Problems if the Vaccine Is Released Too Early

Carefully conducted clinical trials are necessary to identify any problems with the vaccine. For example, studies of a new type of measles vaccine in the early 1990s found that it was detrimental to baby girls, and so it was never licensed to the general population. The existing measles or measles-mumps-rubella vaccine available in the US and other countries is highly safe and effective.

It could also be that the vaccine is not effective in some categories of people. Phase I and II clinical trials have small sample sizes and may not include individuals from high-risk groups. For example, a recently published phase II clinical trial of a COVID-19 vaccine excluded obese people, those with chronic diseases and pregnant women. However, these are all groups that should be able to get the vaccine in the future. More studies, including phase III trials, are necessary to discover if the vaccine works in the general population. Preliminary results should be available by the end of 2020.

The concern is that by introducing the vaccine early, without adequate testing of safety, effectiveness and dosing, the population may be presented with a vaccine which is not safe or not effective, and with little information on which vaccine schedule is best.

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn has said the FDA will not “cut corners” in approving a COVID-19 vaccine in the US despite an accelerated program dubbed Operation Warp Speed.

Rushing to Market

But is there ever an ethical reason to release a vaccine early, even without going through all phases of clinical trials?

Though it would be wonderful to get a vaccine into the population quickly, there could be substantial downsides if researchers and manufacturers cut corners. Imagine a vaccine that often had serious side effects that weren’t caught in small trials before it was widely administered.

Hasty rollout of a COVID-19 vaccine could prime people not only to not trust the COVID-19 vaccine but also to doubt vaccination and public health systems as a whole.

An untested vaccine wouldn’t harm only the people vaccinated. If negative perceptions about the safety or efficacy of a COVID-19 vaccine spread throughout the population, it could limit how many people are willing to get the shot and perpetuate disease transmission.

Trust in vaccination programs is crucial. Russia, in fact, provides an important historical example. In the 1990s, trust in the country’s public health system rapidly decreased, and rates of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination fell as a result. A large outbreak of diphtheria then spread through eastern Europe, leaving over 4,000 people dead.

Hasty rollout of a COVID-19 vaccine could prime people not only to not trust the COVID-19 vaccine but also to doubt vaccination and public health systems as a whole.

Vaccinations should be developed by impartial scientists and evaluated by nonpartisan government officials. By cutting red tape, procedures can be prioritized and sped up, but they must not be skipped.

About the Author

Abram L. Wagner is Research Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the University

of Michigan School of Public Health. He studies the predictors of vaccine-preventable

disease incidence, with a particular focus on vaccine hesitancy. Since 2000, the US

has licensed ten new vaccines and, at the same time, seen the emergence of widespread

vaccine hesitancy leading to outbreaks of measles and pertussis. Wagner’s research

focuses on developing evidence-based programs and policies that help control a broad

range of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Abram L. Wagner is Research Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the University

of Michigan School of Public Health. He studies the predictors of vaccine-preventable

disease incidence, with a particular focus on vaccine hesitancy. Since 2000, the US

has licensed ten new vaccines and, at the same time, seen the emergence of widespread

vaccine hesitancy leading to outbreaks of measles and pertussis. Wagner’s research

focuses on developing evidence-based programs and policies that help control a broad

range of vaccine-preventable diseases.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more articles by Michigan Public Health students, faculty, staff, and alums.

- Listen to the Coronavirus Testing, Turnaround Times, and Immunity podcast episode.

- Support research at Michigan Public Health.