The Worst Disease You’ve Never Heard Of: Caring for Children with Epidermolysis Bullosa

Bailey Brown, BS ’20

“Just when you think things are all right, another blister develops. At the most unexpected times, really. Well, that’s EB.”1

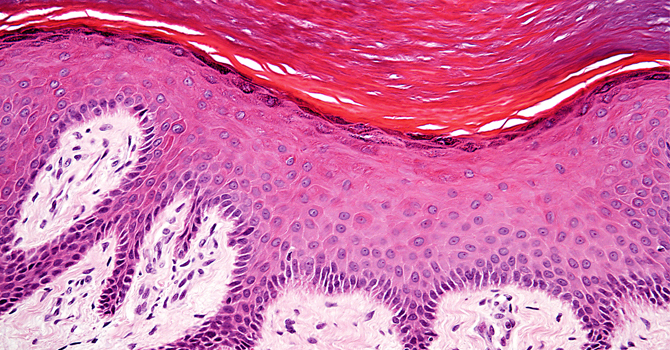

This is the heartbreaking sentiment many parents share when caring for their child diagnosed with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB). Known as the “worse disease you’ve never heard of,” EB is a rare genetic skin disorder characterized by blistering of the skin due to the slightest friction.

Butterfly Children and Their Challenges

Children with EB are often called butterfly children: their skin seems to be as fragile as a butterfly’s wing. Blistering can also occur in the mouth, eyes, and gastrointestinal tract. EB occurs in 1 in 50,000 live births and affects all sexes, races, and ethnicities equally.

Symptoms are often invisible—hidden under bandages, long-sleeves, and pants—which contributes to the public’s lack of understanding about the real psychological, physical, and emotional impact of EB.

The four types of EB all range in severity and impact patients in a multitude of ways. Severely affected children wear extensive bandaging. Most patients with EB can live normal life spans, but more serious forms can be fatal at an early age. Children with EB often experience bullying, find it challenging to engage in social environments, and overall, feel different from their peers. It is not uncommon to be the recipient of stares while others may experience the opposite effect; symptoms are often invisible—hidden under bandages, long-sleeves, and pants—which contributes to the public’s lack of understanding about the real psychological, physical, and emotional impact of EB on a child.

While there is no cure for EB, ongoing clinical trials have developed treatments to manage symptoms. Research on the role of EB on families, however, is severely lacking. Very little is known about how diverse family structures, race/ethnicity, geography, socioeconomic status, and gender affect EB patients and their families.

Caring for a child with EB can easily become a full-time job.

Families and Epidermolysis Bullosa

Nevertheless, research does show that families do face significant challenges. While most EB patients are cared for by their primary care physician or pediatric dermatologist, severe forms of EB require a wide range of specialized healthcare professionals. These families find it challenging to coordinate multiple appointments and have even expressed the need for their own administrative employee. Caring for a child with EB can easily become a full-time job, posing unique challenges for families with low socioeconomic status and nontraditional family structures such as single-parent households.

There are only four comprehensive, interdisciplinary EB treatment centers in the United States. This presents significant barriers to access for patients suffering from severe forms of EB. Furthermore, families have reported significant financial and emotional strain. Specialized bandages are expensive, and wound care may take up to four hours per day. Bandage changes are painful for the affected child, and caregivers often feel extreme guilt during this process. One parent comments, “There is always yelling and crying and screaming: ‘I don’t want this and it hurts so much.’ Yes, that just stabs you in the heart.”1

How Can Clinicians Help?

Many families have expressed their frustration for the lack of EB knowledge among healthcare providers, even in hospital systems. Nutritionists, social workers, psychologists, physicians, and physical therapists must work cohesively to coordinate EB patient care, so continuous clinician education about breakthrough treatments and care plans is essential.

Due to the taxing nature of EB care plans, clinicians can help patients and their families build support networks by connecting them to local support groups, clergy, social workers, and even other families caring for a child with EB. Connecting patients to organizations such as debra of America can help provide additional support. Debra provides free services and programs to the EB community in addition to funding EB research for a cure.

Perhaps another benefit for families is examining the role of diverse family backgrounds on EB care. This will help clinicians consider additional resources for families and work with them more equitably. In the meantime, continuous cultural humility and attentiveness to patient and family needs are key to improving both EB patient and family outcomes.

Notes

1. Scheppingen et al., “The Main Problems of Parents of a Child with Epidermolysis Bullosa,” Qualitative Health Research 18/4 (April 2008):545-556.

About the Author

Bailey Brown, BS ’20, graduated from the University of Michigan School of Public Health

with an undergraduate degree in Public Health Sciences. Her research focuses on the

medical and surgical management of aortic disease in addition to improving acute care

delivery through policy change. Her goal is to continue her education in medical school

and address health disparities through health policy improvement.

Bailey Brown, BS ’20, graduated from the University of Michigan School of Public Health

with an undergraduate degree in Public Health Sciences. Her research focuses on the

medical and surgical management of aortic disease in addition to improving acute care

delivery through policy change. Her goal is to continue her education in medical school

and address health disparities through health policy improvement.