Will COVID-19 Be a Catalyst for Paid Family Leave Expansion?

Batsheva Honig

Master's Student in Health Behavior and Health Education and Health Management and Policy, Nedra Overall Agnew Scholar and Janz Memorial Fund Scholar

Click Here for the Latest on COVID-19 from Michigan Public Health ExpertsThe United States is the only developed country without mandated paid family leave policy for all employees. This fact has raised unique financial challenges for families across the US, who have been and will be impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

As we face one of the largest public health crises of our time, combined with an all-time high unemployment rate, people are taking a hard look at their employment benefits and asking themselves how they can care for their family.

Paid family leave is needed now more than ever.

Paid family leave is the partial or full compensation of time away from work, either for significant family caregiving or serious illness. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provides eligible workers with up to 12 weeks of job-protected, unpaid leave typically used to care for a new child, an immediate family member who is ill, or a personal illness due to a serious medical condition.1

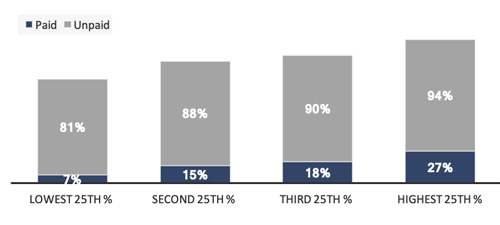

Equity concerns persist. Individuals at the lowest income levels—where we expect to see the most need—have the least access.

As COVID-19 sheds light on income inequalities across the US, it is increasingly clear that lack of paid family leave is a contributor to this inequity. With fewer than 10 percent of workers in the lowest income bracket able to telework, compared to over 61 percent of employees in the highest income bracket, staying home has become a privilege. Lower-income, often minority, workers make up the bulk of the critical infrastructure workers, now more commonly known as “essential workers.” COVID-19 has shown us the importance and need for all essential workers, including but not limited to doctors, nurses, first responders, law enforcement, grocery store clerks, baggers, and stockers. Of particular concern are the many essential workers who earn minimum wage in addition to not being eligible for FMLA or paid family leave.

While 60 percent of the US workforce is eligible for unpaid leave under FMLA, no federal laws require private-sector employers to provide paid leave of any kind.2 As of March 2018, only 16 percent of private industry employees had access to paid family leave through their employers, while 88 percent had access only to unpaid family leave.

Equity concerns persist. Individuals at the lowest income levels—where we expect to see the most need—have the least access. Even the percentage of people eligible for paid family leave ranges from only 7 to 27 percent across the income scale. An increase in paid leave is needed across all income levels.

Access to Paid and Unpaid Family Leave by Wage Percentile

Data retrieved from US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employee Benefits Survey, 2018

Note: Data in each column is not meant to total 100 percent but to show access to

paid and unpaid leave in each income percentile.

Paid family leave is important to the public’s health because it impacts economic stability, a key social determinant of health and well-being. Income is positively associated with life expectancy, higher income being correlated with living longer.

But individuals in need of paid and unpaid family leave face a unique set of challenges that can lead to poor health outcomes. Taking care of an ill or new family member can lead to increased stress levels, further exacerbated in low-income and racial and ethnic minorities. Even family composition—which can include non-blood relatives and extended kin-networks—can create inequity. FMLA and many leave policies use a narrow definition of the “qualifying family members” for whom an employee can take time off to care for. The Department of Labor includes a spouse, child, and parent within their FMLA definitions. Some states—New York, for example—extend this definition to include other family members: domestic partners, grandparents, and grandchildren.

Family leave differs greatly by state. In states like California that have adopted paid leave, we see significant positive effects for women (PDF). Paid leave increases the likelihood that women who have children will return to work, thus helping women support themselves and their families.

The stabilizing benefits of paid family leave are clear and abundant. Paid leave increases post-birth parental care, lowers maternal stress during pregnancy, and ensures a family’s resources and income.

The current pandemic led to an addition in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) requiring certain employers to provide paid sick leave or expanded family and medical leave related to COVID-19. It includes up to an additional 10 weeks of paid expanded family and medical leave at two-thirds the employee’s regular pay. In the coming weeks and months, additional family leave changes are needed. COVID-19 has highlighted the shortcomings of our family leave culture and sparked conversations that should lead to new paid family leave policies in the US.

Researchers can help us move these goals forward by taking actions such as partnering with communities, particularly low-income and underserved communities, throughout the US to better understand and address family composition and need.

We can all contribute to promoting a more positive family leave culture:

- Apply to jobs at companies with paid family leave.

- Ask employers about their policy and negotiate for paid family leave.

- Support local, state, and national policies that support paid family leave.3

- Understand that women often bear a heavier share of caregiving burdens and how this impacts economic earnings, health, and opportunities. Encourage men and nontraditional caregivers to take on more caregiving roles.

- Find caregiver support groups near you for help navigating the process and finding support and resources.

While workers, policymakers, and advocates organize to improve our current paid and unpaid family leave standards, a number of factors still stand in the way. Most notably, we all experience societal pressure to not use family leave even when available due to real concerns about job security.

In theory, family leave allows people to take time off of work. In practice, especially in low-income families, it contributes to financial instability when people cannot cover basic needs like rent, utilities, and food while on family leave. Social stigma also plays a large role for many, especially men, not taking family leave. Cultural change will only begin with behavioral and policy change. One way to accomplish this is by viewing and treating paid family leave as a commitment and not a happenstance.

Additional Resources

- The National Partnership for Women and Families provides helpful information about state comparisons, laws, and mythbusters related to family leave.

- Kaiser Family Foundation article on paid family leave.

- Congressional Research Services, the research arm for Congress, recently published a paper on paid family leave in the US.

- Department of Labor (DOL) official definitions and details.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics on who has access to leave benefits.

Notes

- Paid family leave is different from paid sick leave, also known as “earned sick time” or “sick days.” Paid sick leave is often earned based on hours worked and can be used for a variety of reasons (e.g. short-term illness, preventative health etc.)

- Small employers, with less than 50 employees, are exempt from FMLA as well as employees who do not meet eligibility requirements (worked less than 12 months, worked less than 1,250 hours/year, and so on). Many part-time/temp employees may not meet these additional requirements.

- For example, in 2019, the Healthy Families Act was introduced in the House of Representatives. If it passes, it would require most employers to offer workers paid sick leave. While the bill does not expressly address paid family leave, it is a definite step in the right direction. Later this year, the Federal Employee Paid Leave Act will grant paid family leave to all federal employees. While this bill explicitly applies to federal employees, this is a great opportunity to learn and see the outcomes of paid family leave policy on families’ health and well-being with the potential to advocate for the expansion of paid family leave for the entire US population, both federal and non-federal workers.

About the Author

Batsheva Honig is a master’s student in Health Behavior and Health Education and Health

Management and Policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. She earned

her bachelor's degree in psychology from Washington and Lee University, where she

minored in Poverty and Human Capability Studies. Honig’s interests lie in working

with communities to shape health systems and policies. She hopes to utilize insurance

and payment reform as catalysts for addressing social determinants of health and population

health.

Batsheva Honig is a master’s student in Health Behavior and Health Education and Health

Management and Policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. She earned

her bachelor's degree in psychology from Washington and Lee University, where she

minored in Poverty and Human Capability Studies. Honig’s interests lie in working

with communities to shape health systems and policies. She hopes to utilize insurance

and payment reform as catalysts for addressing social determinants of health and population

health.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more articles by Michigan Public Health faculty, students, staff, and alumni.

- Read more about Honig in Honoring My Grandmother: In Pursuit of a Healthy Future.

- Support research at Michigan Public Health.