The Risk of Neglecting Malaria in the Age of COVID

Jordan Silar, Leah King, Stephanie Ganzi, and Frass Ahmed

Bachelor’s Students in Public Health

Malaria: Past

In 2018 malaria caused 228 million cases of infection and resulted in 405,000 deaths, mostly in children. So why aren’t we concerned about this extremely burdensome disease in the US? The short answer? Money. The long answer? A unique interplay of the biological, environmental and social factors that allow malaria to flourish in the poorest countries in the world.

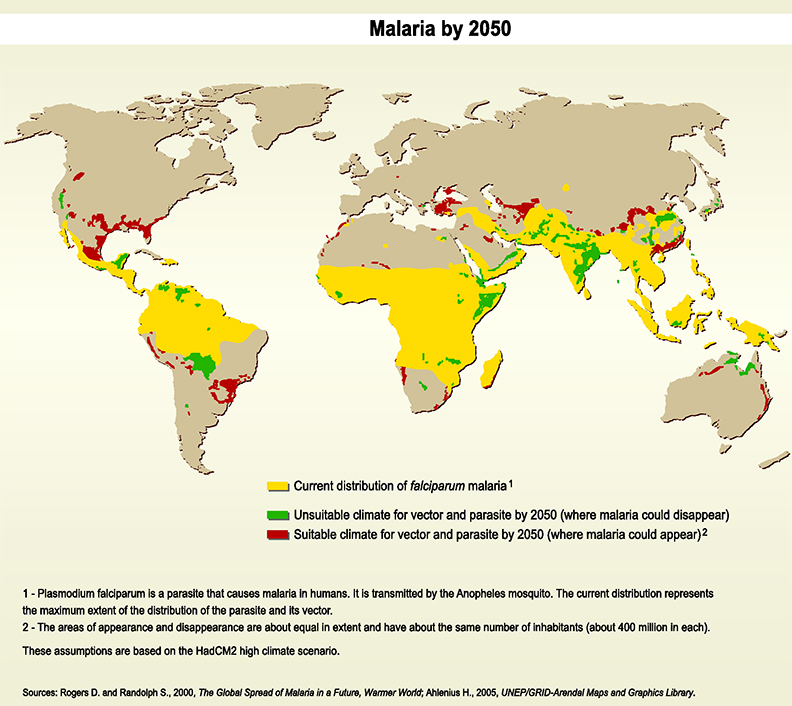

Looking at the graphs of malaria distribution, back in the early 1900s, the burden of malaria was dispersed over most of Earth’s surface. However, today the burden is concentrated in some of the poorest countries in the world. How did this happen? Once malaria-prevention efforts and treatment became widely available in the mid 1900s, only developed nations were able to afford them. Poor nations, on the other hand, could not. Additionally, the World Health Organization’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme, which began in 1955, failed at eliminating malaria and ignored regions that needed the most help.

Malaria: Present

The history of neglect toward malaria in low-income countries is clear. Today, malaria-prevention efforts are targeted to underdeveloped nations such as regions in sub-Saharan Africa because developed nations no longer need to worry about malaria being a major health concern in their own countries. Rich nations now take on the charitable task of helping poor nations that struggle with malaria and cannot fight the disease on their own due to a lack of money, resources, and health care providers. Attention and resources are given to developing nations when the health of developed nations is not being threatened. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic and fear of climate change become major health concerns for developed nations, we worry what this may mean for the future of malaria.

Malaria: Future

As a result of COVID-19, many interventions for various public health issues have been put on hold to deal with the more immediate threat of the pandemic. Since March 2020, halting of vector control activities has been reported despite WHO recommendations against suspensions. Experts expect that rates of malaria—like other infectious diseases—will rise and potentially even double in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The wealthier nations of the world, despite handling their own issues with the pandemic, must not turn a blind eye to malaria endemic regions as they have historically.

Climate and Land Use Change

While social factors greatly impact malaria’s burden and distribution, environmental factors also play a key role. In order for the malaria vector and parasite to develop, there are environmental constraints in temperature, pooled water availability, and a host of other factors. Both deforestation for agriculture and climate change are poised to modify these factors, allowing for endemic malaria in regions previously malaria-free. These changes will still pose the greatest threat to regions with prevalent social risk factors and signify the importance of mitigating such risk as malaria’s ecological range expands.

What You Can Do

The present-day burden of malaria is inequitable, distributed largely by socioeconomic rather than biological factors. As public health practitioners, it’s important to keep global health inequities at the forefront of our minds and actions.

Malaria represents an immense health inequity that demands more attention and research. It’s easy for those living in rich, developed countries to forget about the disease burden borne in less affluent areas, but the cost for our neglect will not be carried by us.

Individuals outside the realm of public health can also assist in the fight against malaria by donating to charitable organizations that work to put in place measures to prevent the spread of malaria. Organizations like the Against Malaria Foundation and Nothing But Nets, which both provide long-lasting insecticidal nets, or mosquito netting, to those in need, and the Malaria No More Foundation, which takes a variety of actions to eliminate malaria globally, help fund the fight against malaria.

With the rising threats of COVID-19 and climate change, global attention and funding for mitigating the inequitable burden of malaria is more necessary than ever.

About the Authors

Jordan Silar is an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan School of Public Health studying Public Health Sciences and Biology. Her interests include maternal and child health, with a particular interest in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. She plans to further her education in medical school and hopes to bring a public health approach to medicine.

Stephanie Ganzi is an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan School of Public Health studying Public Health Sciences. She intends to pursue a career in the medical field, incorporating aspects of public health work with more traditional medical domains.

Leah Kink is an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan School of Public Health studying Public Health Sciences and Biology. They plan to pursue a career in research focused on changes in microbial ecology in relation to anthropogenic factors such as land use change, climate change, and environmental contamination.

- Interested in public health? Learn more here.

- Read more articles about infectious disease.

- Support research and engaged learning at the School of Public Health.