COVID-19 mortality in the California Teacher Study

Ethan Bouche

Master’s Student, Online MPH in Population and Health Sciences

This article was originally published in the California Teachers Study blog.

Ethan Bouche is an online MPH student at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. In this blog, first published on the California Teachers Study (CTS) website, Bouche discusses the Applied Practice Experience (APEx) capstone project he completed in collaboration with CTS. The APEx project is an effort in which students work with community organizations to support real public health work.

Bouche was among a select few online MPH students chosen to investigate avenues of research working with the study's large data set. His project focused on COVID-19 mortality within CTS and its impact on excess deaths. Bouche has been grateful for the chance to engage in real-world public health research as a distance learner living in Japan. Here, he elaborates on his project goals, key findings, and how this experience has shaped his future public health aspirations.

My project was to describe COVID-19 mortality within the California Teachers Study (CTS) and determine whether COVID-19 contributed to excess death among participants. Excess death means the difference between expected death and observed death over a period of time. In other words, did more people die during a specific period than we would expect?

To answer this question, my analysis looked at mortality in the CTS from three different perspectives: the top five causes of death from 2019 - 2021, cause of death groupings, and the age distribution of the top five causes of death.

The top five causes of death

In 2020, COVID-19 replaced congestive heart failure as the 3rd leading cause of death among CTS participants. In 2021, it replaced atherosclerotic heart disease to become the 2nd leading cause of death. Despite COVID-19 suddenly entering the top five leading causes of death, this does not necessarily prove that COVID-19 contributed to excess deaths. It is possible that in the absence of COVID-19, these deaths might have still occurred due to other causes.

| Top Causes in 2019 | % of Deaths | Top Causes in 2020 | % of Deaths | Top Causes in 2021 | % of Deaths | |

| 1. | Alzheimer’s Disease | 12.9% | Alzheimer’s Disease | 12.6% | Alzheimer's Disease | 12.3% |

| 2. | Atherosclerotic Heart Disease | 5.7% | Atherosclerotic Heart Disease | 5.4% | COVID-19 | 5.6% |

| 3. | Congestive Heart Failure | 4.0% | COVID-19 | 4.2% | Atherosclerotic Heart Disease | 4.4% |

| 4. | Acute Myocardial Infarction | 3.6% | Breast Cancer | 3.5% | Lung Cancer | 3.4% |

| 5. | Breast Cancer | 3.4% | Congestive Heart Failure | 3.4% | Breast Cancer | 3.3% |

Top 5 causes of death 2019 - 2021 table. Credit: Ethan Bouche

Cause of death groupings

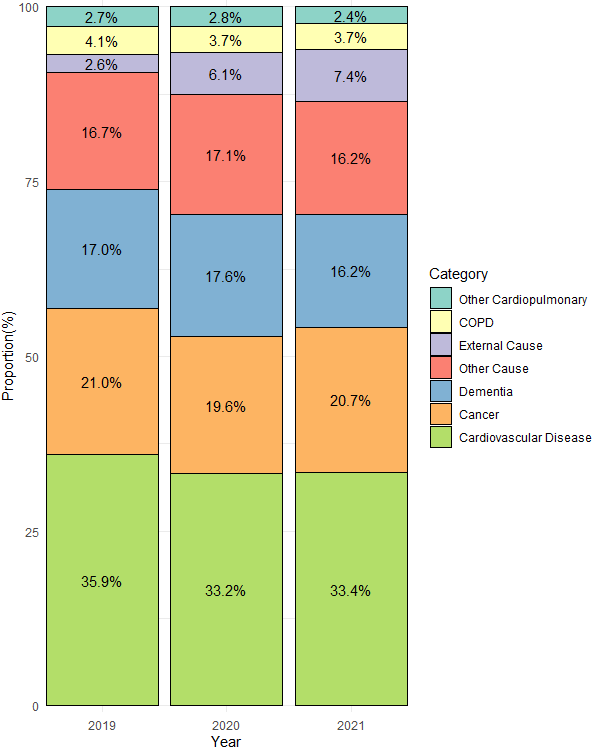

Next, I grouped similar causes of death into seven groups: cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), other cardiopulmonary diseases, external causes, and all other causes of death. I then compared the distribution of deaths in each group in 2019, 2020, and 2021. Grouping the causes of death in this way allowed me to observe if including COVID-19 deaths in the external causes group in 2020 and 2021 corresponded with a decrease in deaths in any of the other groups, which would indicate that COVID-19 likely replaced other causes of death.

Including COVID-19 deaths in the external causes group caused this grouping to rise from the 7th (in 2020) to the 5th (in 2021) largest cause of death group. At the same time, the number of deaths and relative size of remaining eight groups stayed the same in 2020 and 2021.

Cause of death groupings 2019-2021 graph. Credit: Ethan Bouche

Statistical tests showed that distribution of deaths among these seven groups in 2020 and 2021 was significantly different than the distribution in 2019. This finding, combined with the observed stability of the other groupings, suggests that COVID-19 contributed to excess deaths in the CTS.

Age distribution

I also calculated the age-specific mortality rate and age distribution of the common causes of deaths in the CTS. Calculating age-specific mortality helps us identify differences in mortality rates between age groups. I then compared the age distribution of a cause of death in 2020 or 2021 (after the COVID-19 pandemic began) with the age distribution for that same cause of death in 2019.

When I compared the age distribution of COVID-19 deaths to the size of the population in each age group, I found that more older participants died from COVID-19 than we would expect based on the size of the population in that age group. I also found that the age distribution of all causes of death in 2020 and 2021, the two years for which we have COVID-19 death data, was statistically significantly different than the age distribution of deaths in 2019.

Conclusion

This analysis suggests that COVID-19 contributed to excess deaths among CTS participants. Future research is needed to investigate how other factors such as race, socioeconomic status, or healthcare use might affect mortality trends.

Future Goals

This analysis allowed me to apply the skills in epidemiology, biostatistics, and R programming I have learned in my courses to answer research questions in an ongoing study. Through this project, I have found an interest in investigating mortality patterns in a population. As I approach the end of my degree and the start of a new career, I hope to have the opportunity to continue conducting research and analysis in this area.

About the Author

Ethan Bouche is a 2nd year graduate student at the University of Michigan where he

recently completed his Master of Public Health (MPH) in population and health sciences.

His background is in anthropology, and he has been teaching English in Japan since

finishing his undergraduate degree. Through his coursework, he’s realized a passion

for working with health data, and is excited to start a career in health data analytics

soon.

Ethan Bouche is a 2nd year graduate student at the University of Michigan where he

recently completed his Master of Public Health (MPH) in population and health sciences.

His background is in anthropology, and he has been teaching English in Japan since

finishing his undergraduate degree. Through his coursework, he’s realized a passion

for working with health data, and is excited to start a career in health data analytics

soon.