How Language Impacts Public Health

Suzie Genyk

MPH

As a dietetic intern, I spend my time learning about the field of nutrition from a clinical, food service and community health perspective. Having just graduated from the University of Michigan School of Public Health in April, I can't help but see health through this lens when I'm at different rotation sites. I often find myself wondering about the factors that brought an individual to their circumstance, whether it's chronic disease, addiction, or homelessness that they experience.

To help me answer this question, I often call upon the socio-ecological model of health to help me. This model considers multiple factors that contribute to individuals' health—their knowledge and attitude about the world, their social network, institutions they belong to, the community at large, and public policy. These elements help public health professionals understand everything from why chronic disease is common to why someone may be judged as non-compliant in a clinical setting.

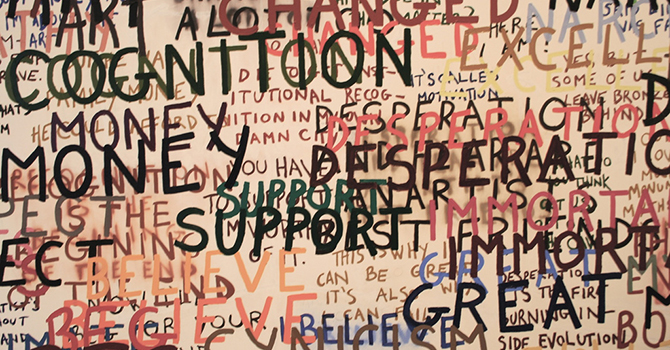

With that in mind, it is important to understand that how we talk about individuals impacts how we understand them.

One of my rotation sites is an eating disorder clinic for adolescents. It was there that I truly understood the importance of language in the context of disease. We do a disservice to those we aim to help by labeling them by their circumstances. For instance, rather than saying "the anorexic patient," we should say "a person with anorexia." When we switch the words around and use people-first language, we no longer define someone by their disease.

At times, nutrition professionals can get tunnel vision and fail to realize a person may have other nutrition or lifestyle concerns beyond the specific condition they are receiving treatment for. Seeing the individual first allows us to treat the whole person and avoid fixating on their disease or circumstance.

This same language paradigm came into play when I had a community rotation with Avalon Housing, a nonprofit organization that provides affordable housing for people who have experienced homelessness. I learned to pay careful attention to my language there. For instance, the language preference is to state an individual experiences homelessness or experiences substance abuse or mental illness rather than calling someone homeless or a drug addict.

Correcting our language allows us to disentangle the person from their circumstance. Whether it's in the broader field of public health or nutrition, people always come first.

About the Author

About the Author

Suzie Genyk, MPH, graduated from the School of Public Health in 2017 with a master's degree in Nutritional Sciences. She is currently a dietetic intern. She also writes blogs for vegan snack company Zana, which was founded by two University of Michigan alumnae.