Painful Problems, No Easy Answers

Kevin F. Boehnke

Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, University of Michigan; PhD ‘17, Environmental Health Sciences

The pain built gradually. In early 2008, it shot into my wrists and hands, worsening when I used a computer or did other repetitive tasks. I took little notice, thinking it was temporary, that it’d go away with time and ibuprofen. When it spread to my forearms and elbows, I grew concerned. It felt like my bones were aching, and the shooting pain hadn’t stopped either. I sought medical attention. My doctor told me I had tendonitis and recommended ibuprofen and physical therapy. I dutifully did both, but the relief they provided was temporary. I ran out of PT appointments and stopped going. I developed an ibuprofen allergy (resulting in a visit to the emergency room) and had to switch to another mild pain reliever. But the pain kept traveling, insinuating itself into my shoulders, neck, back, and legs.

It was devious and mercurial, switching from low-level tenderness to intense stabbing pain over a couple of days. I carefully monitored my activities and tried to excise movements and activities that preceded pain. My world contracted as I cut away more and more. I saw a chiropractor, who suggested that my pain might be caused by spinal misalignment. As with other treatments, spinal adjustments caused temporary relief but not much else. My sleep worsened, leaving me dazed by pain in a haze of helplessness.

Finally, I went to a pain specialist and was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and educated about my condition. Through trial and error and the support of friends, family, and various medical specialists, I developed a toolbox of holistic management approaches that accounted for my social context, preferences, and biology. I slowly built a gentle exercise habit, changed my diet, used appropriate medication, and began to regain a semblance of control of my life.

Looking back, I now realize that this was a defining time for me. Had I gone to the wrong doctor, or been without a strong and well-financed social support system, I may have been lost to opioids. This was 2010, before the current public outcry over the opioid epidemic but during the heyday of pill mills, unprecedented profits for pharmaceutical companies selling opioids, and the medical community’s reductive and unsuccessful reliance on opioids to treat chronic pain. Unknowingly, I was a case study in a nation-wide experiment, pitting reductionist, pill-based treatment against a holistic pain management approach. I later realized that I was one of the lucky ones and that this issue went far beyond me.

The Pain Gets Worse

Chronic pain affects an estimated 100 million Americans, with estimated annual costs ranging up to a staggering $600 billion per year. As I learned, chronic pain is intrinsically tied to many domains of life, including social support, lifestyle, diet, and mood. And it is difficult to untangle these threads. Addressing them all is often necessary for pain management, but there isn’t a cure or a one-size-fits-all solution. This is not always well-received in a culture where people want (or even demand) easy fixes. No single treatment has been shown to be definitively effective, and many therapies only help relieve symptoms in a modest proportion of patients. And this assumes that the patient has been diagnosed with a chronic pain condition. As I found out firsthand, such diagnoses often come after many months or years of frustrating visits with various medical specialists.

This frustration goes both ways, as doctors become understandably aggravated at their inability to help their patients. That, coupled with most doctors’ typically brief formal training on pain management and strictly limited time with each patient, developed a dry grassland just waiting to be lit by the spark of a seemingly straightforward pain management strategy. That spark was Oxycontin.

Fanning the Flames of an Epidemic

In the 1990s, Oxycontin was a new hope for managing chronic pain. Pain had recently been reconsidered in medical practice and was being called a fifth vital sign, like heart rate or temperature. Pain reduction or, better, relief became a new goal. Despite there being no evidence that opioids were safe and effective for long-term chronic pain management, the makers of Oxycontin (and companies with other similar formulations) aggressively marketed these strong opioids, especially among primary care physicians, who had little training in pain management. Sales reps claimed that opioids caused addiction in less than 1% of patients, based on an obscure 1980 letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Many sales reps and doctors argued that the euphoria caused by opioids was mitigated by pain, so there were fewer controls on the doses that doctors could prescribe.

As doctors prescribed opioids, patients demanded more. And as it turned out, opioids were indeed addictive. Though opioids were an amazing tool during surgical procedures and in end-of-life circumstances, they were generally unhelpful for managing chronic pain, with only a very small subset of patients deriving pain relief from opioid therapy. In fact, in some cases sustained opioid intake was shown to cause increased pain sensitivity and pain. Many patients continued to take opioids because other options were unavailable, for fear of increased pain if they stopped, or for off-target effects (such as stress reduction or sleep), for which opioids provide temporary relief but no long-term solution.

Thus, millions of chronic pain patients were getting inadequate treatment, and the rise in opioid prescribing created a dangerous new landscape in the medical community. Pill mills—clinics that solely wrote prescriptions for opioids and other drugs—proliferated, churning out hundreds of prescriptions a day. Many inflated prescriptions were also diverted and sold for easy money, fueling addiction elsewhere. Patients took increasingly higher doses of opioids, and some turned to heroin as the cost of pills became too expensive. Opioid deaths rose and became exacerbated when Fentanyl, an opioid 50 times more powerful than morphine, became more widely available, both legally and on the black market. Reliance on a few powerful, addictive medications had contributed to a nationwide opioid epidemic.

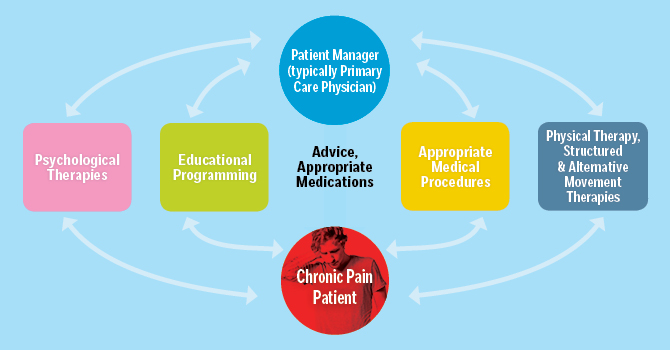

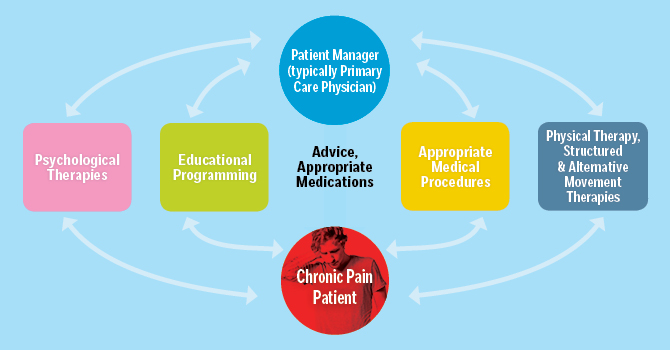

Management Plan for Chronic Pain

Is There Another Way?

Chronic pain wasn’t always treated in this reductive way. In the 1960s, Dr. John J. Bonica, the “father of modern pain relief,” founded America’s first pain clinic at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Plagued by aftereffects of myriad injuries from a career in professional wrestling, Bonica suffered daily from intense pain and channeled this deeply personal understanding into his vision for managing pain in clinical settings. His clinic was based on a multidisciplinary method of pain management. Patients would go through an intense multi-week workshop, visiting multiple specialists and developing individualized medical (therapies) and lifestyle (diet, exercise) strategies that would help them control their pain. This pain clinic also acted as a center for research, pulling together perspectives from these various fields to provide scientific evidence for innovative care.

From there, patients actively participated in and consistently updated their care plan, modulating their own treatment to ensure that it fit their individual needs using the newest techniques available. To do this successfully, doctors collaborated with patients instead of simply directing them to or giving them pills. Physicians needed to account for a patient’s psychological state, diet, relationships, habits, and motivations. Then, as now, this was hard work and took a lot of time. Though this model didn’t make people’s pain go away, it helped them manage that pain, giving them strategies to be functional humans who could be productive and live meaningful lives. And it was effective enough that by the early 1990s, there were hundreds of similar clinics across the country. But during the 1990s, as insurance companies cut back support for medical services, opioids remained cheap and the opioid fever took hold. These clinics became less common, and services in a single location became less available as well as less accessible for those without the means to pay.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Where Do We Go from Here?

Now we are in the midst of a worsening opioid crisis that claimed nearly 50,000 total American lives (13,000 of which were from heroin) in 2016. Many policy makers appear to be viewing the epidemic as a pressing public health problem. As such, instead of using the reductive and ineffective “one-size-fits-all” strategy of incarcerating our way out of this problem, numerous proposals are being considered to address the issue. Some approaches will draw on burgeoning new technology, such as genetically identifying people who are at more risk of opioid addiction to avoid prescribing to them in the first place. Others will focus on clinical policy, reducing opioid prescribing in clinics and the quantity of opioids that can be diverted for nonmedical use by decreasing the quantity and dose of opioids given to patients. Still others will seek to employ potential alternatives to replace opioids for treating chronic pain, or will develop holistic treatment regimens to help chronic pain patients regain function and manage their pain. This list is not comprehensive but does showcase the many ways we are trying to solve this crisis and the different lenses we can bring based on personal history, training, and ideology.

To me, this messy situation illustrates the connections between managing an individual’s chronic pain and addressing the opioid epidemic. As I found out firsthand when trying to heal myself, each single approach is likely too small, too reductionist to tackle such a complex problem. To avoid getting stuck in a reductive trap, it is vital to conceptualize health more broadly. For example, when we speak of precision medicine or precision health, it usually is inextricably linked to genomics-based therapies. While valuable, this provides only one lens through which to view a treatment plan. Analogously, just as doctors must consider a patient’s lifestyle, biology, and emotional and physical health to help a patient with chronic pain manage their treatment plan, so too must we must consider the circumstances that drove this epidemic—in the health care system, societally, economically, culturally, and individually.

I envision the development of a toolbox of nimble multidisciplinary approaches acknowledging that, just like different individuals, different regions of our country will require individualized strategies to address the same problem. The opioid crisis isn’t going away. But under a more integrated and holistic approach, perhaps we can manage it more successfully.

This article first appeared in the fall 2017 issue of Findings, the magazine of the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

- Read about Dr. Kevin Boehnke's journey to a career in public health.

- Support chronic pain research at Michigan Public Health.

- Learn about Michigan Public Health's work on prescription drug monitoring programs.

Sources

- Benedetti, C. and Chapman, C. R., "Third Meeting of Pain Section of Siaarti International J. J. Bonica Memorial," Minerva Anestesiol 71/7-8 (July-August 2005):391–96.

- Bonica, John J., "Basic Principles in Managing Chronic Pain," Archives of Surgery 112/6 (June 1977): 783–88.

- Choo, Esther K., Feldstein Ewing, Sarah W., Lovejoy, Travis I., "Opioids Out, Cannabis In: Negotiating the Unknowns in Patient Care for Chronic Pain," Journal of the American Medical Association, 316/17 (2016):1763.

- Dowell, D., Haegerich. T. M., Chou, R., CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. Journal of the American Medical Association 315/15 (2016):1624–1645.

- Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, "U-M Launches Effort to Prevent Surgery-Related Opioid Addiction across Michigan," October 2, 2017, ihpi.umich.edu/news.

- National Vital Statistics System, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC), "Provisional Counts of Drug Overdose Deaths," August 6, 2017:6–7.

- Porter, J., Jick, H. "Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics," New England Journal of Medicine 302/2 (1980):123.

- Schneiderhan, J., Clauw, D., Schwenk, T. L., "Primary Care of Patients with Chronic Pain," Journal of the American Medical Association 317/23 (2017):2367.

- Tompkins, D.A., Hobelmann, J.G., Compton P., "Providing Chronic Pain Management in the 'Fifth Vital Sign' Era: Historical and Treatment Perspectives on a Modern-Day Medical Dilemma," Drug and Alcohol Dependence 173 (April 2017):S11–S21.

- US Institute of Medicine, Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research, 2011.

- Van Zee, Art, "The Promotion and Marketing of Oxycontin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy," American Journal of Public Health 99/2 (February 2009):221–27.

About the Author

Kevin F. Boehnke is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Research Center at the University of Michigan and a recent graduate of Michigan Public

Health (PhD '17, Environmental Health Sciences).

Kevin F. Boehnke is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Research Center at the University of Michigan and a recent graduate of Michigan Public

Health (PhD '17, Environmental Health Sciences).